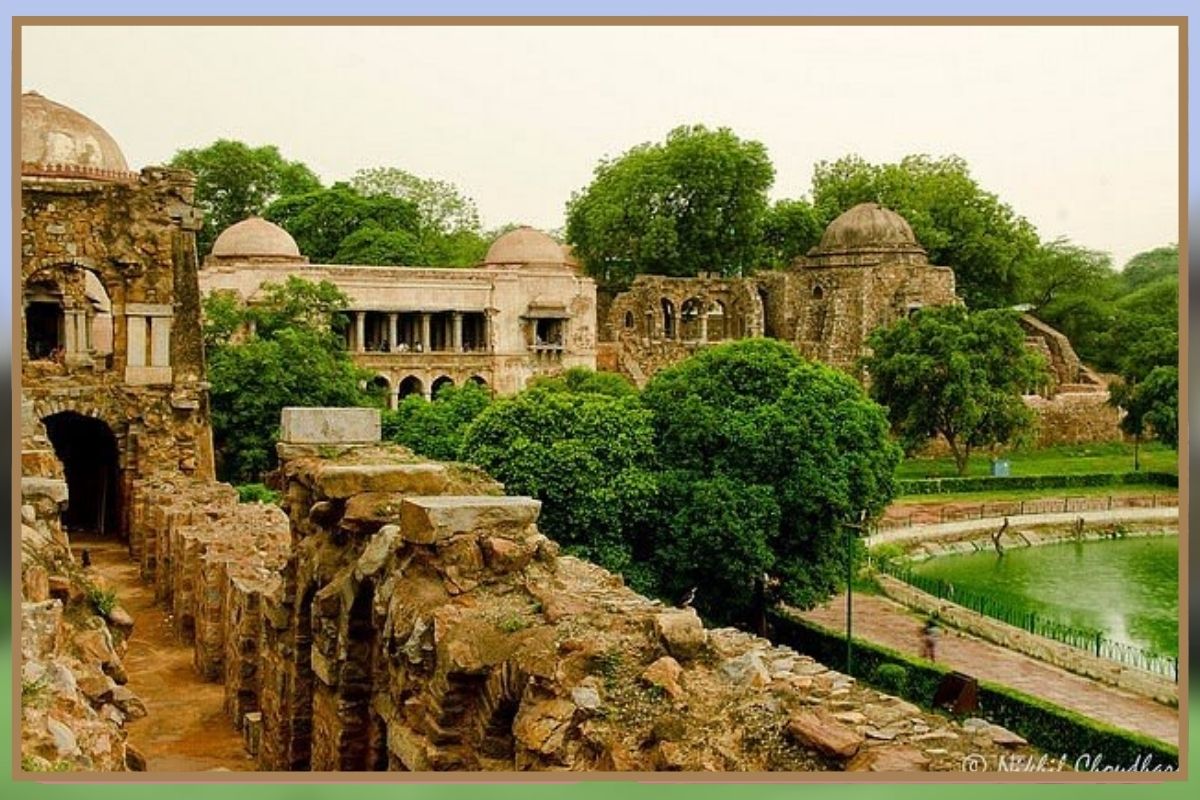

Delhi is a city where ruins whisper louder than walls, where every stone has a tale, and where the past doesn’t merely sleep, it breathes. Among these silent storytellers stands the Hauz Khas Stepwell & Tomb Complex, an architectural theatre where water engineering, royal ambition, and intellectual brilliance converge. It is not just a collection of broken arches and forgotten tombs; it is a living palimpsest still holding Delhi’s pulse, shifting effortlessly between medieval grandeur and modern vibrancy.

Walk through its pavilions, and you’ll find yourself torn between two worlds, on one side, echoes of Islamic scholarship and Sultanate vision, and on the other, the laughter of college-goers, the hum of art cafés, and the timeless shimmer of the lake. Hauz Khas isn’t a relic; it’s a rhythm, syncing the tempo of the 14th century with the heartbeat of today’s Delhi.

The Royal Tank: Alauddin Khilji’s Bold Beginning

To understand Hauz Khas, you must begin with water. Around 1296–97 CE, Sultan Alauddin Khilji, Delhi’s powerful and often controversial ruler, was crafting his fortified capital, Siri. But a fortress without water is only a mirage. The Sultan, who spent much of his reign fending Mongol invasions, also understood the subtler war against thirst.

And so, he ordered the excavation of a mammoth reservoir. At its peak, it spanned nearly 50 hectares, stretching about 600 by 700 metres with a depth of four metres, a lifeline carved into Delhi’s dry soil. Initially known as Hauz-i-Alai, it was designed not just as a tank but as a declaration of might, abundance, and permanence. This was water as power, water as architecture, water as empire.

Every monsoon, the reservoir brimmed with collected rain, quenching the needs of Siri’s soldiers and citizens. Hauz Khas was both a shield and a statement in a land where survival often depended on seasonal whims.

Firuz Shah Tughlaq: The Visionary Restorer

Time, however, is cruel to monuments. After the Khiljis declined, Hauz-i-Alai began to choke under silt and neglect. By the mid-14th century, its waters had almost disappeared into dust. Then came Firuz Shah Tughlaq (1351–1388 CE), a ruler remembered as much for his benevolence as his buildings.

Firuz Shah didn’t just restore the tank; he reimagined the entire space. Around its glimmering waters, he built an L-shaped madrasa that became one of the finest centres of Islamic learning in the medieval world. Here, students studied astronomy, theology, philosophy, and literature, their voices mingling with the sound of wind over water.

At the heart of the complex, Firuz Shah raised his own tomb, a square, plain yet dignified structure. Unlike other rulers who sought ornate afterlives, his resting place exudes simplicity, echoing humility before eternity. Scattered around are smaller tombs of scholars and courtiers, each stone a reminder that this was not just a palace of kings but also a sanctuary of minds. Thus, Hauz Khas transformed from a utilitarian tank into a cultural constellation, where water nourished bodies and wisdom.

A Maze of Stories: Between Arches and Gardens

If you wander through Hauz Khas today, you might pause at the pavilions, open halls with sloping roofs where students once debated the nature of the stars. You might brush your hand against the coarse red sandstone and wonder about the masons who used quick lime and surkhi to strengthen these walls. Or you might sit quietly near the tomb garden, where whispers say that scholars still linger in spirit, guarding their madrasa of centuries past.

There are lesser-known tales, too. Locals speak of how Firuz Shah, despite being a ruler, personally oversaw repairs, introducing ingenious restoration techniques. They recall the madrasa as not just a classroom but a buzzing township, Tarababad, the “city of joy,” where learning was life, and every student added a verse to Delhi’s growing intellectual saga.

The Stepwell That Fed a Capital

Amid these ruins lies the stepwell, a marvel of medieval engineering often overlooked beside the tank. Built in Alauddin’s era, it was a water source combining practicality and elegance. Each descending step promised relief in harsh summers, each stone a silent prayer for abundance.

The Persian word Hauz Khas itself, “Royal Tank”, captures the essence of this hydraulic heart. It wasn’t just water collection; it was rain harvesting on a civilisational scale. The stepwell and reservoir formed a network mirrored Delhi’s seasonal rhythms, turning scarcity into sustainability long before the term existed.

Lessons for Today: Water Wisdom in a Thirsty City

Fast-forward to modern Delhi, a metropolis gasping under water scarcity, sinking groundwater, and vanishing lakes. The irony is sharp: What Firuz Shah restored with foresight is what we now neglect with indifference.

The medieval rainwater harvesting system at Hauz Khas remains a masterclass in sustainable design. Its red sandstone lining prevented seepage, its channels carried runoff from surrounding ridges, and its connection to stepwells created a decentralised water web. This wasn’t an isolated tank; it was part of a city-wide ecosystem of baolis, nullahs, and reservoirs, ensuring balance even in dry months.

Imagine if Delhi revived this wisdom today, clearing encroachments, reactivating catchments, and restoring tanks. Not only would it ease the burden on aquifers, but it would also make the city resilient against floods, droughts, and climate change. Hauz Khas is not a ruin but a manual waiting to be reread.

The Complex as a Modern Soul Space

Yet, Hauz Khas is not trapped in the past. Step into the Hauz Khas Village that surrounds the ruins, and you’ll find a different energy: art galleries, bohemian cafés, fashion boutiques, and buzzing nightlife. Students sketch the domes in charcoal; photographers chase the golden hour by the lake; families picnic on the lawns; couples carve their histories on ancient steps.

It’s a paradox, half museum, half playground. Some may call it commercialisation, but perhaps it is continuity: a site of learning and living that has simply adapted its syllabus for the 21st century. Firuz Shah’s madrasa once hosted debates on astronomy; today, the cafés around it echo with debates on cinema, startups, and politics. The pulse of dialogue endures.

Why Hauz Khas Still Matters

The Hauz Khas Stepwell & Tomb Complex is more than a heritage site. It is a mirror, reflecting what Delhi was, what it is, and what it could be. It binds the city’s three significant needs: water, wisdom, and community.

From Alauddin’s imperial might to Firuz Shah’s scholarly generosity, from forgotten centuries to Instagram reels, Hauz Khas continues reinventing itself. It tells us that heritage is not about freezing time; it’s about keeping the dialogue alive between past and present. Perhaps the deepest lesson it whispers is this: cities thrive not by building higher but by remembering deeper.

The Tank That Became a Teacher

Hauz Khas are not just stones and water. It is Delhi’s biography, written in sandstone and reflected in ripples. It teaches us that a reservoir can be more than utility; it can be philosophy, architecture, community, and even rebellion against forgetting.

As Delhi struggles with its identity in the chaos of urban sprawl, the Hauz Khas Complex stands calm, reminding us that progress is not about erasing the old but weaving it into the new. The reservoir once quenched Siri’s thirst; today, it quenches Delhi’s longing for history, culture, and reflection.

Hauz Khas is and will remain a royal tank of memory, a place where water once ruled, where wisdom once flourished, and where Delhi finds its reflection even today.

Also Read: Adham Khan’s Tomb: The Maze of Betrayal and the Price of Power

You can connect with DNN24 on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel.