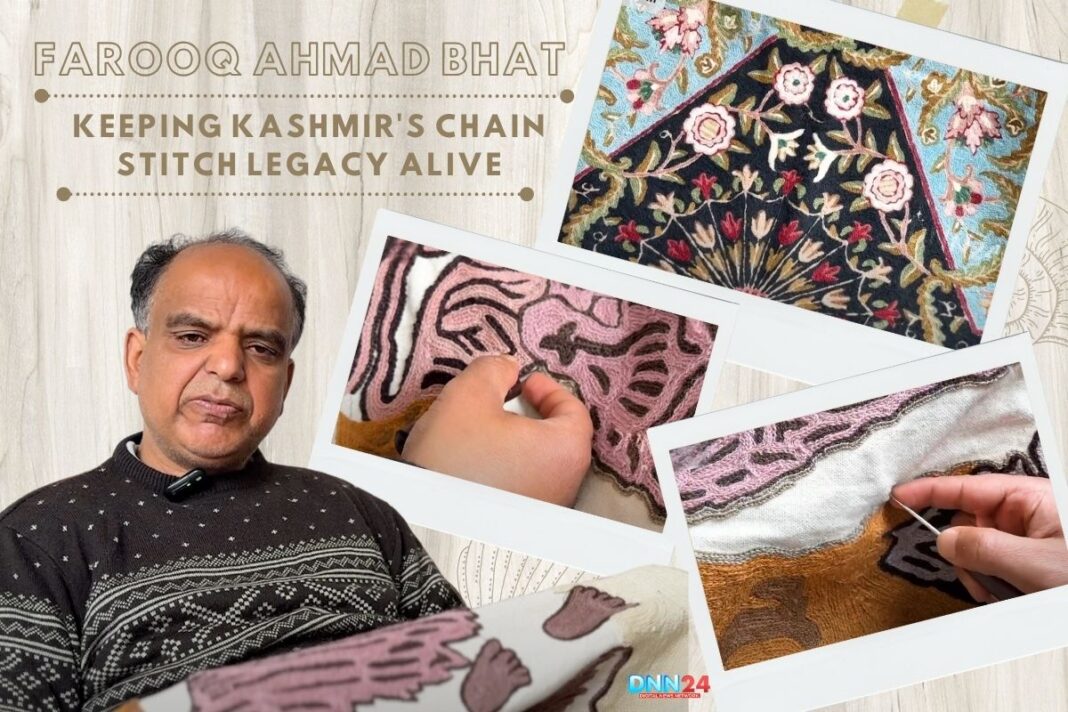

In the heart of Kashmir, where every thread tells a story and every stitch carries the weight of generations, sits Farooq Ahmad Bhat – a guardian of one of India’s most beautiful traditions. This third-generation master craftsman has dedicated over 20 years of his life to preserving the exquisite art of chain stitch embroidery, creating breath-taking rugs and designs that capture hearts across the world. The same family workshop lasting 70 years is the message to the world of the beauty of a handmade work of art.

What makes Farooq’s work truly special is not just the technical perfection, but the soul that goes into every piece. Chain stitch, or ‘chain seeti’ as it’s known locally, is a technique where each stitch connects to the previous one, creating an unbroken chain of beauty, much like the relationships that bind families together across generations. Using a special tool called ‘aari’ – a combination of needle and hook – artisans create intricate patterns that range from basic chain stitches to complex designs like rosette chains, twisted chains, and zigzag patterns.

Farooq Ahmad Bhat: A Legacy Under Siege

The conditions of the genuine Kashmiri handicraft today are heartbreaking. While machine-made alternatives flood the market with their speed and low costs, genuine handmade pieces like Farooq’s struggle to find their rightful place. The problem isn’t just about competition – it’s about survival. A lot of talented artisans are leaving the art of their ancestors due to the fact that they are not able to make ends meet to feed their families.

“The main issue is that artisans don’t get proper wages,” explains Farooq with visible concern. “Middlemen and exporters make the money, while the craftsman who creates the actual art gets very little.” This is a terrible truth that made numerous traditional artisans want to change their profession and forget about the centuries of experience and mastership. A community of artists once has now become reduced to just a few select individuals who have chosen not to bow down to the tradition that has existed amongst them.

The irony of this fact is very harsh. All the international markets place a very high price on handmade products, particularly in Europe, where they are selling like hotcakes. Meanwhile, the craftsmen who are making these artworks are making just enough money to have their daily bread. One object that requires a couple of weeks to work on may fetch the artisan a small portion of the amount that it will eventually fetch in the market.

Farooq Ahmad Bhat: The Art That Conquers Time

Creating a chain stitch masterpiece is like performing a meditation in motion. The step involves copying the design to an item of fabric, and then the selection of colors and threads to be used is done carefully. That is followed by the true test of patience—months of working on one item when the entire artist is totally focused on the execution of the design.

“First, we prepare the base fabric, then it goes to the designer for printing. After that, our work begins – deciding the color combinations, which colors to use where,” Farooq explains the meticulous process. “The most challenging part is the color combination. Deciding which color goes where requires years of experience and artistic vision.”

What sets chain stitch apart from other embroidery forms like crewel work is its completeness. In chain stitch, the background fabric completely disappears under the embroidery, creating a solid, rich surface that seems to glow with life. A skilled artisan can complete approximately one square foot per day, and that’s working with full concentration and expertise.

A Glimmer of Hope- the GI Tag

Recently, there’s been a breakthrough that has filled Farooq and his community with hope. The Geographical Indication (GI) tag approval for Kashmiri chain stitch embroidery promises to protect authentic products from cheap imitations. This publicity implies that the buyers can now be able to distinguish between true handmade products and machine-created imitations, particularly the international buyers.

“The GI tag is wonderful news for us,” says Farooq with excitement. Now, when people buy our products abroad, they’ll know they’re not machine-made. This will help distinguish our authentic work from imitations.” This may become the lifesaver that Kashmiri artisans need.

GI tag also solves one of the greatest problems: the cheating that occurs when a machine-made product is passed off as handmade, most particularly in the market abroad. European customers, who attach high value to handmade crafts, are not able to separate machine embroidery from hand embroidery, and this brings unfair competition to the real artisans.

Fighting for Fair Wages and Recognition

The government has set up several training centers to imbibe new generations with this art form, but the main issue remains—once young people have learned to do this particular art, they struggle to make a good living out of it. “When someone learns this art and realizes they can only earn ₹100-150 per day, how can they support their family?” asks Farooq, highlighting the economic reality that threatens the craft’s survival.

Farooq, however, thinks that direct relations with the clients may alter everything. “If clients come to us directly instead of through middlemen, we can earn much better. If those who make big profits share even a small percentage with artisans, it would make a huge difference.” This desperation leads him to the guided efforts, disregarding the obstacles on their way.

The difference between machine work and handmade work is incomparable. While a machine can produce ten pieces in a day, a skilled artisan takes four to five days to produce only one piece. This time factor automatically increases the cost of handmade products and, more importantly, multiplies their value by infinity as art.

Farooq Ahmad Bhat: A Vision for the Future

Farooq Ahmad Bhat’s optimism about the GI tag is infectious. He believes that with proper recognition and protection, the number of chain stitch artisans in Srinagar could grow from the current 10 to 200 in the coming years. “If artisans get better earnings, more people will join this profession,” he says confidently.

This ancient art form, dating back to the Mughal era, represents more than just Kashmir’s cultural heritage – it’s a symbol of human patience, skill, and artistic vision. Every chain stitch piece carries within it the artist’s dedication, the region’s history, and the hope for a better future.

The story of Farooq Ahmad Bhat is ultimately a story of resilience and hope. It reminds us that there is a person behind every piece of stunning handmade stuff who lets his or her heart and soul reach the extraordinary. As consumers and art lovers, we can help these artisans by buying their authentic handmade goods and paying them the fair cost of their wonderful work.

The future of Kashmir’s chain stitch tradition depends not just on skilled artisans like Farooq but on all of us who can recognize, appreciate, and support this priceless cultural treasure.

Also Read: Hilal Ahmad Wani: Kashmir’s Silent Cricketer Conquered World Deaf Cricket League

You can connect with DNN24 on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel.