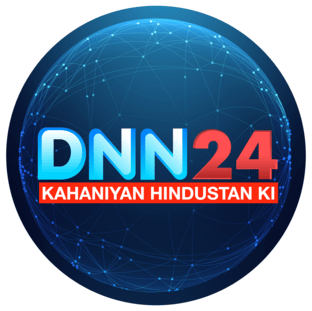

Imagine this: A kid in the 1980s would go into a clean glass river after school, drink right out of the mountain streams, and swim without worries. Fast forward to modern times, and that river now has infection risks from just dipping your toe in. This stark transformation isn’t just nostalgia talking; it’s the alarming reality Professor Ghulam Jeelani has witnessed firsthand in Kashmir.

Prof. Ghulam Jeelani, the Dean at the School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Kashmir, and the National Geoscience Award 2024 winner, has spent over twenty years researching the Himalayan hydrology. His research reveals a troubling truth: Kashmir’s water bodies – from mighty rivers to sacred springs – face an unprecedented crisis. The valley, which was once famous for its clean waters flowing through all the villages, is currently struggling with pollution, climate change, and mismanagement to the extent that not only is the environment under threat, but the very base of the Kashmiri life and economy is in danger as well.

Prof. Ghulam Jeelani on Kashmir’s Water Wealth: A Divine Gift Under Threat

Kashmir’s water resources are nothing short of extraordinary. Water is present in all possible forms, liquid and solid, surface and underground, and the Himalayas have it all, from the soaring glaciers to the numerous springs that decorate the land. Rivers such as the Jhelum, lakes of pristine beauty, hundreds of ponds, wetlands, glaciers, and even permafrost are found in the valley. This abundant water wealth isn’t just about scenic beauty; it’s the lifeline that sustains Kashmir’s entire existence.

Kashmir is blessed with a natural water management system, which makes it very special. The topography drains south to north, and the essential springs are found in southern Kashmir – places such as Verinag, Achabal, and Martand Nag. These springs, in old times held in reverence and guarded, yielded at one time such pure water that men used to drink out of them. The natural “banking” system works like clockwork: winter precipitation falls as snow, gradually melting through spring and summer to regulate stream flows, recharge groundwater, and maintain the delicate balance sustaining life here for centuries.

Prof. Ghulam Jeelani on The Economic Lifeline: How Water Powers Kashmir’s Future

Each rupee earned in Kashmir is somehow related to water. Agriculture and horticulture—the valley’s primary economic drivers—are entirely water-dependent. This resource is valuable to the world-famous Kashmiri rice, Saffron fields, and Apple orchards. Tourism, which brings visitors from across the globe, exists because of Kashmir’s water-blessed landscapes. The lush green meadows, flowing rivers, and serene lakes that define Kashmir’s beauty would not exist without abundant, clean water.

Hydropower generation represents another crucial economic pillar, with Kashmir’s rivers holding enormous untapped potential. The interdependence is so strong that without water, the economy would fail in one sector and the whole economy. This isn’t theoretical—it’s happening right now. The degradation of the quality of water and its irregular supply affect every sector. Farmers are faced with erratic water supplies, tourists prefer not to use contaminated water bodies, and the natural processes that sustain all this start to fail.

Prof. Ghulam Jeelani on The Climate Change Factor: Rain to Snow

Climate change isn’t a distant threat in Kashmir – it’s a reality reshaping the water landscape. Prof. Jeelani explains that while annual precipitation hasn’t dramatically decreased, its form and timing have changed considerably. The culprit? Rising winter temperatures that convert snow into rain fundamentally alter Kashmir’s natural water storage system.

Snow acts as nature’s savings account, storing water during winter and releasing it gradually through spring and summer. This natural banking system maintains a consistent flow of water in streams, consistent groundwater recharge, and consistent springs discharge all year round. However, this regulated system fails as snow melts into rain due to warmer temperatures. Instead of being gradually absorbed into the intricate system of springs and streams on which Kashmir relies, rain drains off in days, to depressions and then to the ocean. The result? The rainfall would cause floods, and the water scarcity would result in the erratic and irregular water availability that currently defines most of the water sources in Kashmir.

The Human Factor: How We’re Poisoning Our Wells

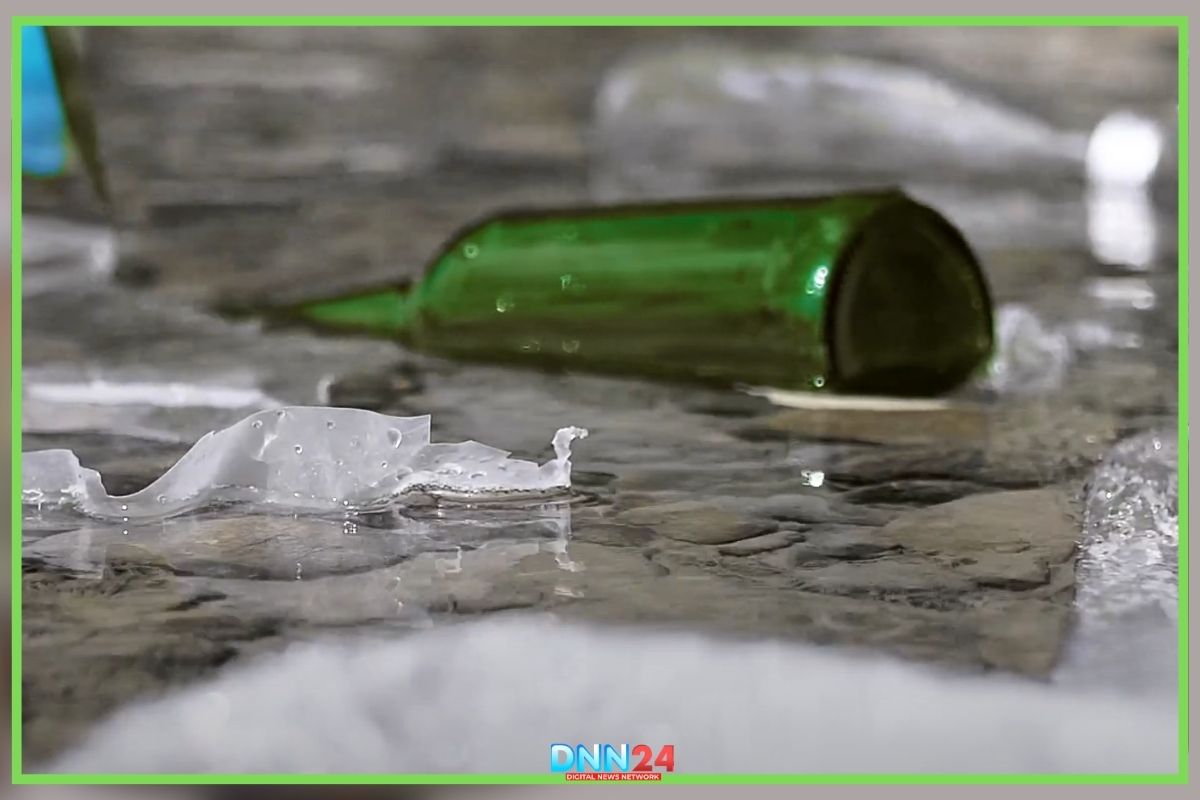

While climate change grabs headlines, Prof. Jeelani argues that human actions pose an even greater threat to Kashmir’s water bodies. The transformation from pristine to polluted isn’t gradual—it’s shockingly rapid and entirely avoidable. All water bodies within Kashmir have plastic waste, diapers, sanitary pads, and other garbage thrown carelessly by people.

Pollution is not just the visual trash. Poorly managed sewage has polluted both the surface waters and the groundwater. Most homes, even in the presence of government toilet building programs, do not construct proper septic systems. People tend to use ring systems with gaps, so the faecal matter can easily contaminate groundwater instead of using concrete septic tanks, where proper decomposition occurs. The outcome is a dual pollution wherein the surface waters are directly disposed of waste and the groundwater is polluted by faulty sewerage systems. This isn’t just an environmental issue – it’s a public health crisis affecting the water that eventually reaches people’s taps.

Prof. Ghulam Jeelani on Springs: The Holy Waters Which birth-gave Civilisation

Kashmir’s springs hold special significance beyond their practical utility. Historically, these water sources were sacred, and religious and cultural activities guarded them, guaranteeing their purity. People would gather at springs daily and socialise as they conserved these vital resources. Most of the springs had fish, and local cultures did not allow any kind of pollution or destruction of these water ecosystems.

Several large springs in southern Kashmir, especially in places such as Anantnag, have long been used as a source of water in the valley. Some springs, especially those containing sulfur compounds, were therapeutic to the skin and orthopaedic problems. Certain springs also had natural healing properties due to their warm temperature and mineral content, which people used to depend on throughout generations. Nevertheless, encroachment, pollution, and altered precipitation patterns have worsened most of the springs, affecting water supply and social and cultural activities around them.

The Government Challenge: Surplus Not Scarcity

Addressing Kashmir’s water crisis requires systemic change that goes beyond individual responsibility. As much as mass awareness is essential, the magnitude of the issue requires the government’s involvement on several levels. Plastic waste, which lands in all regions of Kashmir, including in the far-flung areas and mountainous regions, needs systematic collection and disposal mechanisms. Most waste management activities today merely transfer problems instead of solving them.

Prof. Jeelani states the necessity of accountability systems such as traffic enforcement. As it was with automated challans in altering driving behavior, the same must be appliedton environmental violations. The government should organise the right waste segregation and disposal mechanism at village, tow,n and district levels. Above all, there must be a system of proper decomposition of non-biodegradable waste as opposed to temporary transfer of waste to another location.

A Call to Action: Saving Kashmir’s Water Legacy

Kashmir’s decision is black and white: take action now or forever lose this valuable water heritage. Prof. Jeelani’s message is clear—the pristine waters that previous generations enjoyed and protected must be preserved for future generations. This isn’t just about environmental conservation; it’s about maintaining the foundation of Kashmiri identity, economy, and way of life.

Individual responsibility and systemic change are needed to provide the solution. Every person must understand that Kashmir’s water bodies are a shared heritage, not someone else’s problem. Meanwhile, governments should establish adequate waste management systems, implement environmental laws, and establish sustainable water resource management. The scenic beauty that draws tourists to this region and the world, the agriculture that feeds the people and the cultural practices that characterise Kashmir rely on clean and abundant water.

It is the action day. As Prof. Ghulam Jeelani on warns, what we’re witnessing isn’t a temporary drought but the beginning of a new reality unless immediate steps are taken. Kashmir’s water crisis is solvable, but only if everyone – from individuals to institutions – commits to treating these precious resources with the respect and protection they deserve. It is up to us: clean water for our children or a history of environmental degradation. Kashmir’s waters have nurtured civilisation for millennia – now it’s our turn to encourage them.

Also Read: From Ashes to Hope: The Journey of Atchayam Trust’s Mission to End Begging in India

You can connect with DNN24 on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel.