The road through Sanquelim bends past red earth and coconut groves before stopping at something most tourists miss completely: five plain openings cut into a laterite cliff. No grand entrance, no long queues, just simple rock doors that look almost abandoned. These are the Arvalem Caves, also called Pandava Caves, carved fifteen centuries ago into soft red stone that shapes much of Goa’s landscape. While millions flock to beaches and parties, these chambers near Harvalem village stay quiet, visited mainly by those who care to look beyond the obvious.

The caves hold a strange mix of Buddhist origins, Hindu worship, and epic legend pressed into one compact stone story. Walk inside, and the air cools instantly, the rock walls smell of damp earth, and you stand where monks once meditated, where Shiva lingas now receive prayers, and where locals still insist the Pandava brothers hid during their long exile. The question hanging in that cool shadow is simple: how did five modest caves become a meeting point for so many layers of faith and imagination across the centuries?

First Look: Stone That Refuses To Shout

Arvalem Caves appear without warning or ceremony. The laterite outcrop rises modestly and plain, its five entrances arranged in a straight line like ordinary doorways rather than temple gates. There is no towering shikhara reaching skyward, no elaborate carvings announcing divine presence, just bare rock shaped by human hands into a functional shelter. The reddish-brown laterite, formed by tropical weathering, gives the structure an earthy, humble appearance that makes visitors pause and look twice.

This is not a monument demanding attention; it waits patiently for those willing to stop correctly. Around the base, children from nearby houses play cricket, their shouts mixing with occasional prayers from the small shrine inside, creating a scene where ancient heritage and daily village life exist without formal separation. Old men sit on stone ledges sharing stories with anyone patient enough to listen, treating the caves not as museum pieces but as familiar neighbours. Women carrying water pots sometimes rest in the shade, vendors set up small stalls selling coconut water, and the whole atmosphere carries a relaxed informality that larger heritage sites lost long ago.

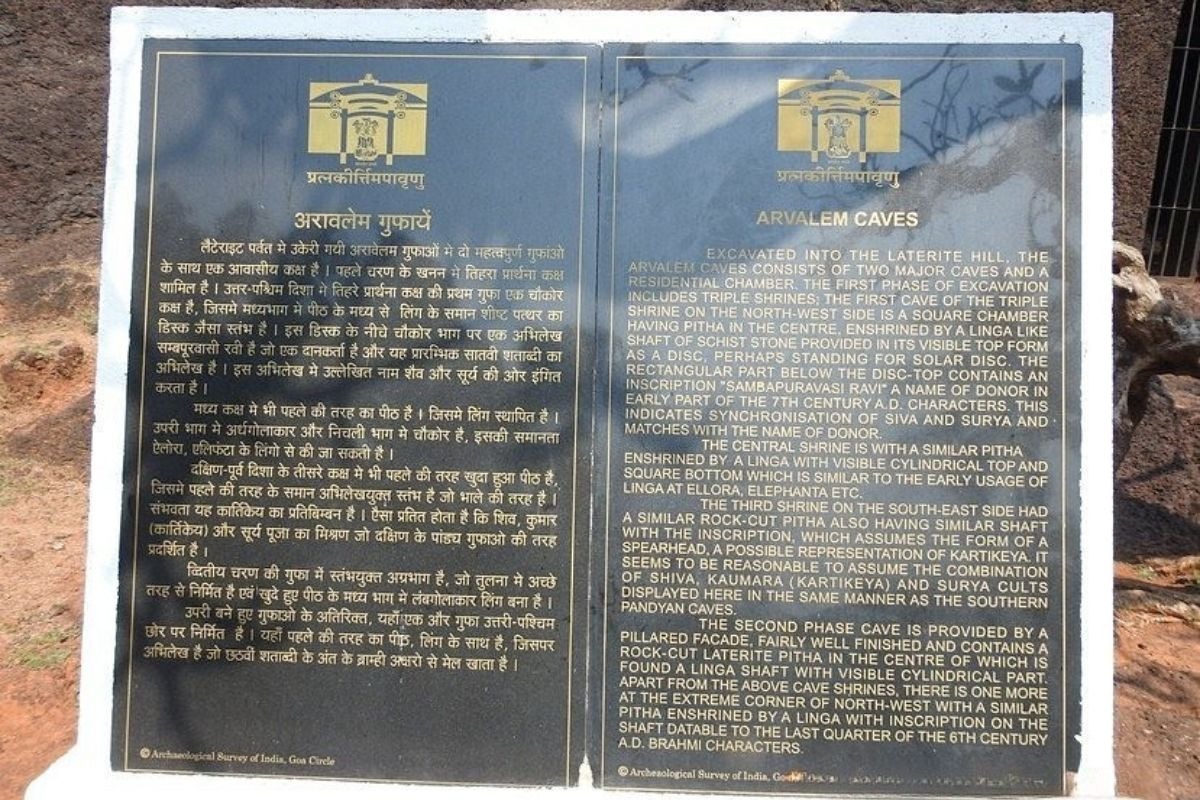

The Archaeological Survey maintains basic signage, but there are no audio guides or elaborate visitor centres. What you see is what you get: five rock-cut cells, a few granite Shiva lingas, and the accumulated weight of centuries pressed into laterite that still feels connected to living earth. This simplicity, rather than diminishing importance, somehow amplifies it, stripping away usual heritage tourism packaging to reveal something more direct and honest.

Pandava Legend: When Myth Claims Geography

Ask any local about these caves, and the answer comes instantly: Pandava Caves. The official name is Arvalem, but in daily conversation, the Mahabharata brothers own this place completely. The story is straightforward: during their long exile, the five Pandava brothers wandered far from Hastinapur, eventually reaching this corner of Goa, where they found shelter in these laterite formations. Each brother supposedly claimed one of the five chambers as his temporary home, turning the caves into a secret refuge from enemies pursuing them through years of vanvaas.

The neat alignment of five caves with five brothers creates satisfying symmetry that oral tradition loves, and the legend has stuck with remarkable staying power across generations. For Hindu pilgrims visiting from Maharashtra and Karnataka, this connection transforms a simple archaeological site into sacred ground, a physical place where mythological heroes once walked and planned their return to power. Historical evidence for Pandava presence is precisely zero. Scholars date the caves to the 5th-7th centuries CE, long after any possible Mahabharata events, and the architectural style points to Buddhist or early Hindu monastic use rather than warrior hideouts.

Yet this gap between history and legend does not weaken the story’s grip on local consciousness. By linking these caves to the great epic, villagers placed their home geography onto the sacred map of India, making Goa part of a narrative stretching from the Himalayas to the southern ocean. When a grandmother brings her grandson here and points to one chamber as Bhima’s room, another as Arjuna’s space, she is not confused about archaeology; she is teaching him how to see the landscape as a story. The legend works because it gives people a way to care about old rock, to treat five simple caves as something more than curiosities from a distant century.

Buddhist Birth And Hindu Transformation

Step through any entrance, and the temperature drops immediately. The laterite walls, several feet thick, hold the coolness of earth, creating a natural climate perfect for meditation in tropical heat. The interior layout is simple: long, rectangular chambers with low, flat ceilings and plain walls bearing marks from ancient cutting tools. There are no elaborate pillars, no decorated capitals, no narrative reliefs. The design speaks of function over display, shelter over spectacle, and many historians see clear parallels with early Buddhist rock-cut viharas where monks lived and meditated away from village distractions.

Period dating, roughly 5th to 7th century CE, aligns with Buddhism’s strong presence in western India before its gradual decline. Arvalem Caves likely began as precisely that: a small monastic retreat carved by Buddhist communities who valued the quiet laterite hillside and nearby water source. But walk further inside, and the story shifts. Each chamber now contains a granite Shiva linga, some more weathered than others, standing in sharp material contrast to the soft red laterite surrounding them. These lingas were clearly added later, brought from elsewhere and installed as objects of Shaivite worship, transforming what may have been meditation cells into active shrines.

One linga carries particular significance: a short inscription in Brahmi script, written in Sanskrit, that scholars read as “Sambalur vasi Ravih”. Paleographic analysis dates this inscription to the 6th-7th century, placing it in the Bhoja period when Goa’s rulers patronised Hindu temples and gradually replaced earlier Buddhist structures. This single carved line anchors Arvalem Caves firmly in documented history rather than pure legend. What makes the site particularly interesting is that both layers remain visible. The basic architecture still speaks in Buddhist terms, while worship objects declare Hindu identity. The caves become a three-dimensional textbook showing how sacred spaces get reused across centuries without completely erasing previous chapters.

Waterfall And Living Worship

Arvalem Caves do not stand alone. A few hundred meters away, Harvalem waterfall crashes down in a wide foamy curtain, especially impressive during the monsoon when the river runs full. The falls drop into a deep green pool surrounded by rocks and vegetation, creating a dramatic natural setting that draws families and photographers. This proximity of ancient caves and an active waterfall is not coincidental; the water source likely influenced the original location choice. Today, tourism operators package the two sites together, promoting a heritage-and-nature circuit that attracts more visitors than either attraction would on its own.

On weekends, the space fills with picnicking families and children splashing in shallow edges while parents explore the caves. Just beside the waterfall stands Rudreshwar Temple, a more recent structure dedicated to Shiva, continuing the Shaivite worship tradition that transformed Arvalem Caves centuries ago. The temple sees regular worship, with priests conducting daily rituals and larger ceremonies during important Hindu festivals. Mahalaya Amavasya, the new moon day dedicated to honouring ancestors, attracts large crowds as families perform shraddha rituals for departed souls. On these festival days, the whole area pulses with activity: the caves receive flower garlands and oil lamps, the temple courtyard fills with chanting and incense smoke, and the waterfall provides a constant natural soundtrack to human devotions.

For local Hindus, this is not a tourist site but a living sacred landscape where different elements combine to create a complete pilgrimage experience. However, popularity brings complications. The waterfall, beautiful and inviting, is also dangerous. The pool is deeper than it appears, the current is stronger than casual observers realise, and accidents have occurred over the years. Local residents report occasional crocodile sightings in the river. Safety infrastructure remains minimal: no lifeguards, few warning signs, and limited barriers. This gap between growing tourism profile and introductory safety provisions has become a point of friction.

Why Arvalem Caves Still Matter

In a Goa dominated by beaches and Portuguese architecture, Arvalem Caves offer a completely different narrative, a quieter and older story most visitors never hear. For historians, the caves provide a compact case study in religious transition, showing how Buddhist spaces became Hindu shrines while retaining traces of original purpose. The Brahmi inscription offers concrete evidence of 6th-7th-century patronage in Goa. For local communities, the site serves a different function. The Pandava legend gives the caves emotional and spiritual weight, making them feel connected to the great epic that defines Hindu cultural identity.

Continuing worship at Rudreshwar Temple and within the caves keeps the site alive in daily religious practice rather than leaving it frozen as a relic. Families bring children here not just to see old stones but to teach them stories, to connect them to something larger than the immediate present. The informal atmosphere allows the caves to function as an extended village commons, a place where heritage and everyday life mix without the need for official mediation.

For travellers willing to venture beyond Goa’s standard itinerary, Arvalem Caves offer something valuable: a more layered picture of the place. Instead of just beaches, visitors find Buddhist history, Mahabharata mythology, Shaivite devotion, and natural beauty combined in one small geographic area. The caves do not shout their significance; they wait quietly for those curious enough to ask questions. In an age demanding the new and spectacular, these modest rock chambers remind us that meaning does not always require scale. Sometimes, five simple doors in a cliff face hold more depth than a dozen grand monuments, if we care to look correctly.

Also Read: Eklakhi Mausoleum: Pandua’s One Lakh Rupee Royal Secret

You can connect with DNN24 on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel.