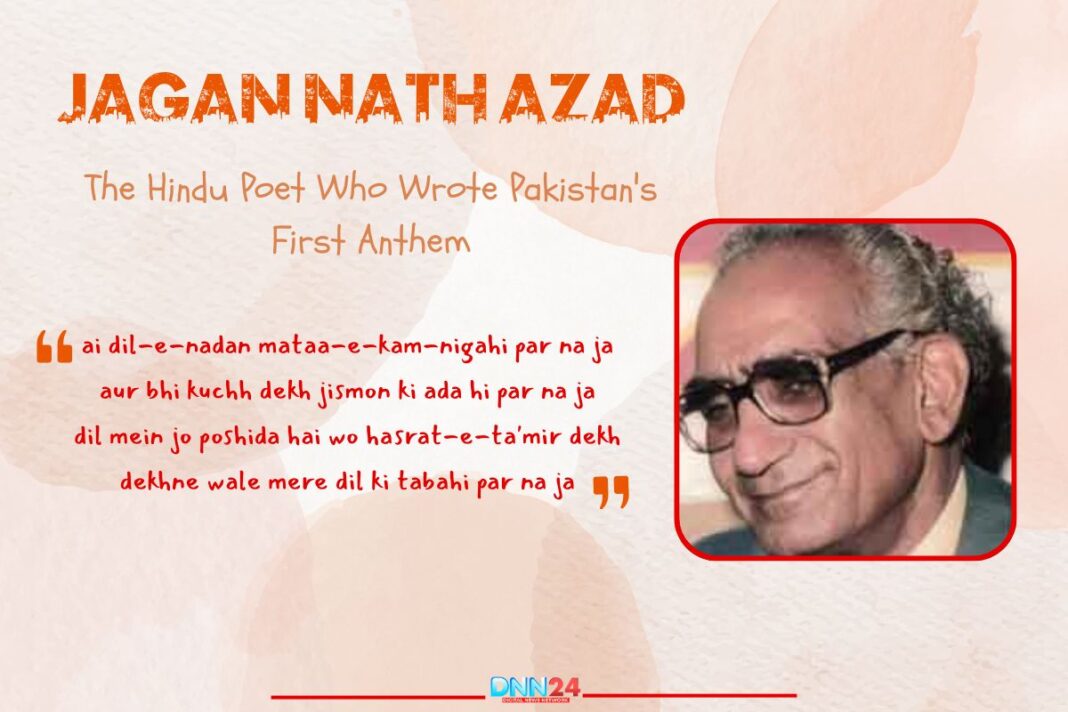

What drives a Hindu scholar to compose verses for a newborn Islamic nation while his own neighbourhood burns in communal violence? Jagan Nath Azad’s life answers this question in ways that textbooks never could. Born in 1920, when Punjab still belonged to undivided India, this man became the bridge nobody asked for, but everyone needed.

ek nazar hi dekha tha shauq ne shabab un ka

Jagan Nath Azad

din ko yaad hai un ki raat ko hai KHwab un ka

His pen touched both nations, writing anthems for Pakistan while bleeding for India. Today, when borders seem more complicated than ever, his story arrives like a forgotten letter, reminding us that poetry once mattered more than politics.

Early Life: When Words Became Destiny

Isa Khel in 1920 was not much to look at. Dust covered everything, and opportunities were scarce. But inside one modest home, a father named Tilok Chand Mehroom was planting seeds that would bloom across continents. Young Jagan Nath watched his father recite Ghalib’s couplets, pen his own verses, and host gatherings where words flowed like rivers.

KHayal-e-yar jab aata hai betabana aata hai

Jagan Nath Azad

ki jaise shama ki jaanib koi parwana aata hai

Mehroom was friends with Allama Iqbal, the philosopher-poet whose dreams would later shape Pakistan. Those friendships meant Jagan Nath grew up surrounded by literary giants. Hafeez Jalandhari, who would write Pakistan’s official anthem, treated the boy like a nephew.School came naturally to someone raised on poetry.

mumkin nahin ki bazm-e-tarab phir saja sakun

Jagan Nath Azad

ab ye bhi hai bahut ki tumhein yaad aa sakun

Mianwali first, then Rawalpindi, where DAV College and Gordon College refined what home had started. At Gordon, he edited the college magazine, tasting the power of published words. By the time Lahore called, offering him the editor’s chair at Adabi Dunya magazine in his early twenties, Jagan Nath Azad was ready.

phir lauT kar gae na kabhi dasht-o-dar se hum

Jagan Nath Azad

nikle bas ek bar kuchh is tarah ghar se hum

Punjab University added Persian and Oriental literature to its knowledge. But it was the streets that completed his education. He joined the Communal Harmony Movement, travelling through villages where Hindus and Muslims were beginning to eye each other with suspicion. He spoke of unity when the word was becoming dangerous.

Partition: The Anthem Nobody Remembers

August 1947 arrived like a storm nobody could outrun. Lahore, overnight, transformed from a cultural capital into a bloodbath. Jagan Nath Azad found himself the last Hindu resident in Ram Nagar, surrounded by sixty thousand people who had fled or been killed. Yet Radio Pakistan found him, carrying a request that seemed absurd. Muhammad Ali Jinnah wanted Azad to write the first national anthem. A Hindu. For an Islamic republic. In the middle of Partition’s worst violence.

ab main hun aap ek tamasha bana hua

Jagan Nath Azad

guzra ye kaun meri taraf dekhta hua

Five days was all the time between the request and the deadline. Azad produced “Aye Sar Zameen-e-Pak,” verses that praised Pakistan’s soil as pure as stars, that spoke of wounds being healed, that imagined a secular future for a nation born in religious division. Radio Pakistan played it once at midnight on August 14, 1947. Then silence. Conservative voices complained immediately. The anthem was shelved and later replaced by Hafeez Jalandhari’s composition. But for one midnight hour, Azad’s dream of unity had a voice.

meri umr-e-rawan hai aur main hun

Jagan Nath Azad

ye jins-e-raegan hai aur main hun

Violence finally drove him out. His family had already fled to Delhi. The train to India carried a man whose heart was splitting. Behind him, friends like Ahmed Nadeem Qasmi and Wazeer Agha remained on the Pakistan side. Delhi received him not as a hero but as another refugee needing work. Milap newspaper hired him as assistant editor. Employment News came next. More government jobs followed in Labour, Information, Food, and Tourism ministries. He became a bureaucrat who happened to write poetry, or perhaps a poet forced to play bureaucrat.

Building Bridges Through Literature

The 1960s and 70s found Azad in Srinagar, working for the government but doing something more valuable in his spare time. He met everyone. Sheikh Abdullah, the lion of Kashmir. Mirwaiz Umar Farooq, the religious leader. Politicians, poets, ordinary people. He carried no agenda except conversation and understanding. While armies faced each other across the Line of Control, Azad was having tea with people on both sides.

main dil mein un ki yaad ke tufan ko pal kar

Jagan Nath Azad

laya hun ek mauj-e-taghazzul nikal kar

He travelled to Pakistan regularly, attending mushairas in Lahore and Karachi, as if the old days had never ended. Pakistani literary circles welcomed him as one of their own. He was proving something important. That literature existed outside politics. That Urdu belonged to anyone who loved it, regardless of which flag they saluted. Through him, a literary conversation continued that official channels had long abandoned.

tera miTna dil-e-nashad bahut yaad aaya

Jagan Nath Azad

ye saman raat bahut yaad bahut yaad aaya

The government retired him in 1977, but Jammu University immediately appointed him as Professor and Head of the Urdu Department. His focus turned to Allama Iqbal. He translated Iqbal’s Javed Nama. He began a massive five-volume biography, though floods destroyed two volumes of research. Eventually, he produced eleven books on Iqbal in Urdu and English, becoming the acknowledged authority. A Hindu scholar had become the foremost interpreter of the poet who dreamed Pakistan into existence.

A Literary Empire: Seventy Books and Counting

Seventy books. That number represents more than productivity. It represents obsession, dedication, and hunger to document everything. Azad wrote poetry collections that won awards. Atish-i-Gul earned him the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1958. Pakistan awarded him its Gold Medal, a rare honour for an Indian. His ghazals appeared in collections like Nawa-e-Preshan, Kahkashan, and Justujoo. “Chalte rahe hum tund hawaon ke muqabil” remains among his most quoted lines, a statement of perseverance that could describe his entire life.

auj-e-kamal-e-sher hai hamd-o-sana-giri

Jagan Nath Azad

mujh ko sikha gai hai yahi kuchh suKHanwari

But Azad pioneered something unusual in Urdu literature: the travelogue. Pushkin Ke Des documented his travels through the Soviet Union. Columbus Ke Des covered America. He wrote books about Canada, Europe, and China. These were not casual tourist observations but serious literary works. Urdu had never seen anything quite like them. He was showing readers that their language could describe any place, capture any experience.

nashe mein hun magar aaluda-e-sharab nahin

Jagan Nath Azad

KHarab hun magar itna bhi main KHarab nahin

Anjuman Taraqqi-i-Urdu made him President in 1993. He held the position until he died in 2004. Awards piled up: Minar-e-Pakistan, Shiromani Sahityakar, and recognition from institutions in both countries. His desk at the Rajiv Gandhi Institute remained occupied until weeks before cancer took him at 84.

The Poet Who Spoke Truth to Power

December 1992. Babri Masjid falls to a mob. Azad is on a plane when he hears the news. He pulls out paper and writes verses that cut like glass: “Tune Hind ki hurmat ke aaine ko toda.” You broke the mirror of India’s honour. The poem does not spare Hinduism. It does not spare anyone. Muslims see a Hindu who shares their pain. Hindus who still believe in the secular dream find voice in their anger.

koi izhaar-e-gham-e-dil ka bahana bhi nahin

Jagan Nath Azad

ho bahana bhi jo koi to zamana bhi nahin

Fast forward to today. India and Pakistan still glare at each other. Social media amplifies every conflict. But Rekhta Foundation’s digital platform is introducing Azad’s work to young people who have never heard of him. His ghazals get shared, sometimes remixed. YouTube channels feature his verses. Students studying India-Pakistan relations stumble across his story and find something textbooks never mentioned: that complication existed, that friendship survived, that one man’s life could contradict every straightforward narrative about Partition.

jalwa tera is tarah se nakaam na hota

Jagan Nath Azad

hum tur pe hote to ye anjam na hota

His final wish was simple: a song of peace for both nations. He never got to write it, or perhaps he spent his whole life writing it in pieces. The wish sounds naive until you remember this man actually wrote Pakistan’s first anthem while living through Partition. He had already done impossible things.

Why Azad Matters Today

What does Azad teach us that policy papers cannot? That identities are complicated, that you can love Urdu without abandoning Hinduism, that national borders need not become personal walls. His life challenges every simple story about India and Pakistan. He should not have existed according to the logic that drove Partition. Instead, he became Urdu’s greatest champion in India and Pakistan’s unofficial literary ambassador.

itna bhi shor tu na gham-e-sina chaak kar

Jagan Nath Azad

ishq ek latif shola hai is ko na KHak kar

He was not a saint or superhero. He was a government employee who wrote on the side, a father of five, a man who took buses and trains like everyone else. Success came late. Recognition was partial. But he never stopped writing, never stopped believing that words mattered, never stopped crossing borders both physical and mental. Cancer finally stopped him at 84, but by then the work was done.

tamam ‘umr mere dil ko ye ghurur raha

Jagan Nath Azad

ki ek lamhe ko ye bhi tere huzur raha

So when tensions rise, and social media fills with hate, Jagan Nath Azad’s story arrives like a counter-argument written in verse. It says that someone once lived who refused the easy categories, who loved two nations that could not love each other, who wrote in a language that both claimed and neither owned exclusively. His life was the poem. Everything else was just commentary.

Also Read: Aazam Khursheed : The Poet Who Made Faces Speak & Still Matters

You can connect with DNN24 on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel.