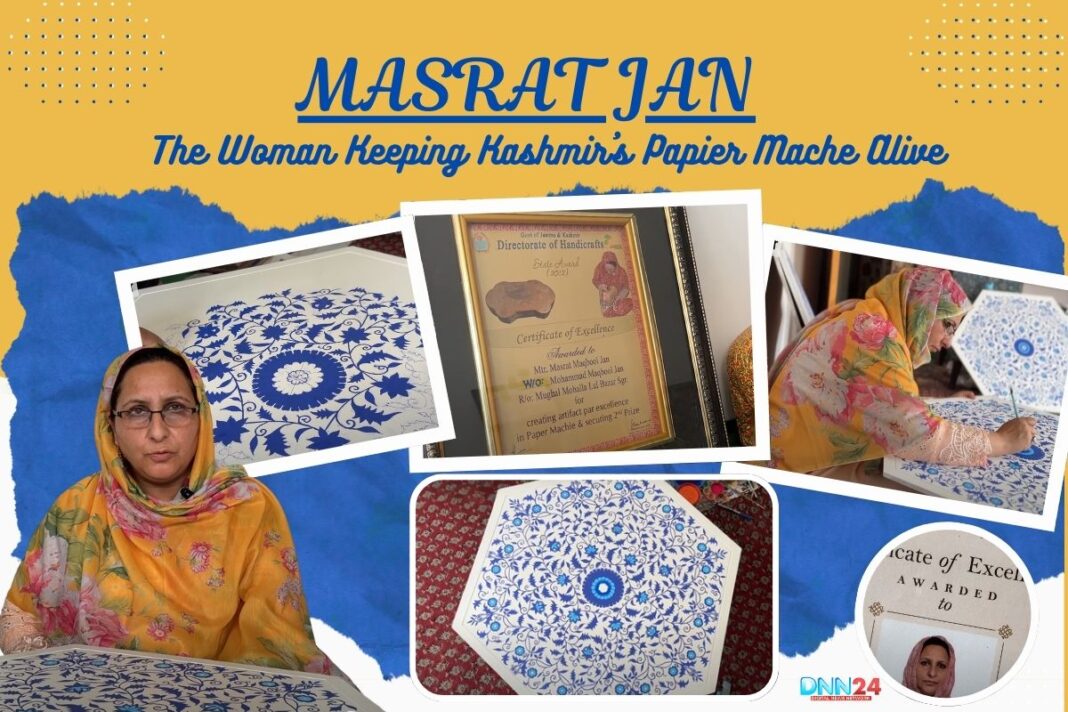

In the small, serpentine lanes of Lal Bazar in Srinagar, in whose crisp mountainous air the aroma of saffron blends always, lives a lady who has transformed an old tradition that has been handed over to her in silent ways. Masrat Jan, a 50-year-old artist with paint-stained fingers and dreams larger than the Dal Lake itself, has done something extraordinary. She has breathed new life into Kashmir’s dying papier mache tradition while breaking centuries-old gender barriers.

For generations, papier mache in Kashmir was strictly a man’s domain. The art of making beautiful articles out of pulp of paper and adorning them with brilliant colours was also handed down by fathers to their sons, by uncles to nephews and collection was done by the women-folk. Masrat, however, without fear, became different. She picked up the brush in a world that told her it wasn’t meant for her hands, and today, she stands as a beacon of change with three prestigious state awards adorning her modest workshop.

Her journey began in childhood at her maternal uncles’ workshop, where she watched mesmerised as skilled hands transformed simple paper into works of art. “I fell in love with this craft watching my mama work,” she recalls, her eyes lighting up with the same wonder she felt as a child. “There was something magical about seeing plain paper become beautiful bowls, boxes, and decorative pieces.”

Masrat Jan: Making it the Passion to Profession

What started as a childhood fascination soon became Masrat’s calling. The craft became incorporated in her mind when she got married to a family of papier mache artisans. Unlike most of the ladies who lived during her era and were required to concentrate on home chores, Masrat managed to strike a balance in all aspects. She also took care of her house and her kids, and she developed her artistic abilities.

“I work on my art for two to three hours daily,” she explains, carefully applying gold leaf to a jewellery box. Some pieces take months to complete. You cannot rush this art—every stroke, every colour, every detail needs patience and love.” This commitment is evidenced by her workshop, which she has established in one of the corners of her residence. On the shelves are partly completed works, each bearing a tale of careful craftsmanship.

She made her breakthrough with a success story when her first award-winning work was a fruit bowl that demonstrated not only her technical expertise but also her creativity in terms of traditional designs. This was succeeded by a jewellery box, to which there was recognition, followed by a decorative wall hanging. Each award wasn’t just personal validation; it was proof that women could excel in this traditionally male-dominated field.

Masrat Jan: Art with a Social Mission

But Masrat’s vision extends far beyond personal success. Today, she dreams Kashmir could be a place where all the young girls get a chance to learn this beautiful work, where women find income and pride in papier mache. “We work on everything—wall hangings, table lamps, flower vases, panels, jewellery boxes, and even Quran stands,” she says, gesturing to the variety of pieces in her workshop.

Her house is now an informal training institute where ladies in the neighbourhood go to learn. She educates them not only about the technical part of the trade but also about its business perspective. “Through this work, I run my household, educate my children, and maintain financial independence,” she proudly states. For many women in conservative Kashmiri society, where stepping out for work can be challenging, Masrat’s model offers the perfect solution—earning respect and money while staying close to home.

Masrat Jan: A Vision of Tomorrow

What sets Masrat apart is her understanding that art isn’t just about creating beautiful objects; it’s about preserving culture and empowering communities. Her work has extended the classical papier mache as she has tried the six-dimensional potential and modern designs to the classic aspects of the art.

Masrat’s biggest dream is to see papier mache taught in schools across Kashmir. “The government should introduce this in schools, even if it’s just for two hours a week,” she advocates passionately. “Children will only learn if it’s part of their curriculum. They won’t come to individual workshops, but if it’s in schools, every child will learn.”

She sees a future not only of papier mache in Kashmir but also of all the traditional crafts of Kashmir, suzani embroidery, wood carving, and carpet weaving. Through early exposure to these arts, she thinks that there will be a generation of people who will appreciate and uphold their cultural heritage and, at the same time, have some practical skills in economic independence.

“Today’s times are different,” she reflects, her voice carrying the wisdom of someone who has seen societal changes firsthand. Both men and women need to work hard. When there are ten people in a house, everyone should contribute. The old days when women could sit at home are gone.

Her message to young women is clear and empowering: “Don’t just sit idle. There’s so much work available. You can learn sozni, wood carving or paper-mache. The thing is, that, even by mastering a single skill appropriately, you may earn a lot. Why work as a salesperson for 2,000-3,000 rupees when you can earn the same or more from home while preserving your culture?”

Masrat Jan: The Artist’s Legacy

When Masrat works, there’s something almost meditative about her process. Her hand guides her brush through centuries of brushwork with certainty; each brush mark is thoughtful and significant. She doesn’t just apply paint; she tells stories. Her designs tend to look like Kashmir itself, and they include the chinars, the flowers, and the geometrical shapes that have been embodied in Kashmiri art for centuries.

“Every piece I create carries emotions,” she explains. “I don’t just paint with colours; I paint with feelings. When someone buys my work, they’re not just getting a decorative item—they’re taking home a piece of Kashmir’s soul.”

Her studio has been the symbol of a silent revolution. Women all over the neighbourhood attend not simply to learn the craft but to have their voices, their freedoms to independence. In a society where women’s contributions are often overlooked, Masrat has created a space where they can flourish.

Today, as global interest in handmade, sustainable crafts grows, Masrat’s work has found appreciation beyond Kashmir’s borders. Her pieces are sought after by collectors who understand that each item represents not just artistic skill but also cultural preservation and women’s empowerment.

Conclusion: It is not Just Art

Masrat Jan’s story is more than just that of a successful artisan. It’s a tale of courage, perseverance, and vision. She has opted to preserve an art that touches our roots in a society that is fast mechanising and producing on a mass scale. She has managed to show that tradition and change should not begin a conflict with each other; they can dance, and together, they form something new, something beautiful and valuable.

Her legacy isn’t just in the beautiful pieces she creates or the awards she has won. It’s in the women she has inspired, the cultural traditions she has preserved, and the barriers she has broken. Masrat Jan is not just keeping Kashmir’s papier mache alive; she is ensuring it thrives for generations to come.

In her paint-stained hands and determined spirit lies the future of Kashmir’s cultural heritage—vibrant, inclusive, and full of possibilities.

Also Read: Mohammad Saleem Pathan’s Free Martial Arts Training Transforms Kashmir’s Youth

You can connect with DNN24 on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel.