The villagers in the Indian villages, still living in the age of stone ages, with the technological rays unkinded on their part of the country, their traditions are the fonts, writing their ink & identity and existence in the world. The tribal tattoo culture stands exceptionally prominent among traditional Indian practices. Modern city tattoos underline a complete difference from these traditional tattoo marks. Indian tribal communities consider tattoos to carry deep significance toward who they are and what they believe and how they live their lives. Human history records this body art practice as a continuous practice dating over thousands of years. “These marks on our skin tell stories that words cannot,” explains, an elderly woman from the Baiga tribe of Madhya Pradesh. Complex symbolical patterns decorate her facial features and arms which she received as a young child.

Ink & Identity: Origins of Tribal Tattoos in India

Uses of the tribal tattoos or other related forms of body art can especially be dated back to the earliest forms of art and history in India. It is practised widely throughout various parts of the world and is commonly referred to as Godna in many of the regions Body scarification is a practise that entails putting ink on the skin with simple tools such as needles and natural colours. The custom is inherent in the culture and logic of the movement of the tribes and can be associated with such ideas as protection, purification and initiation.

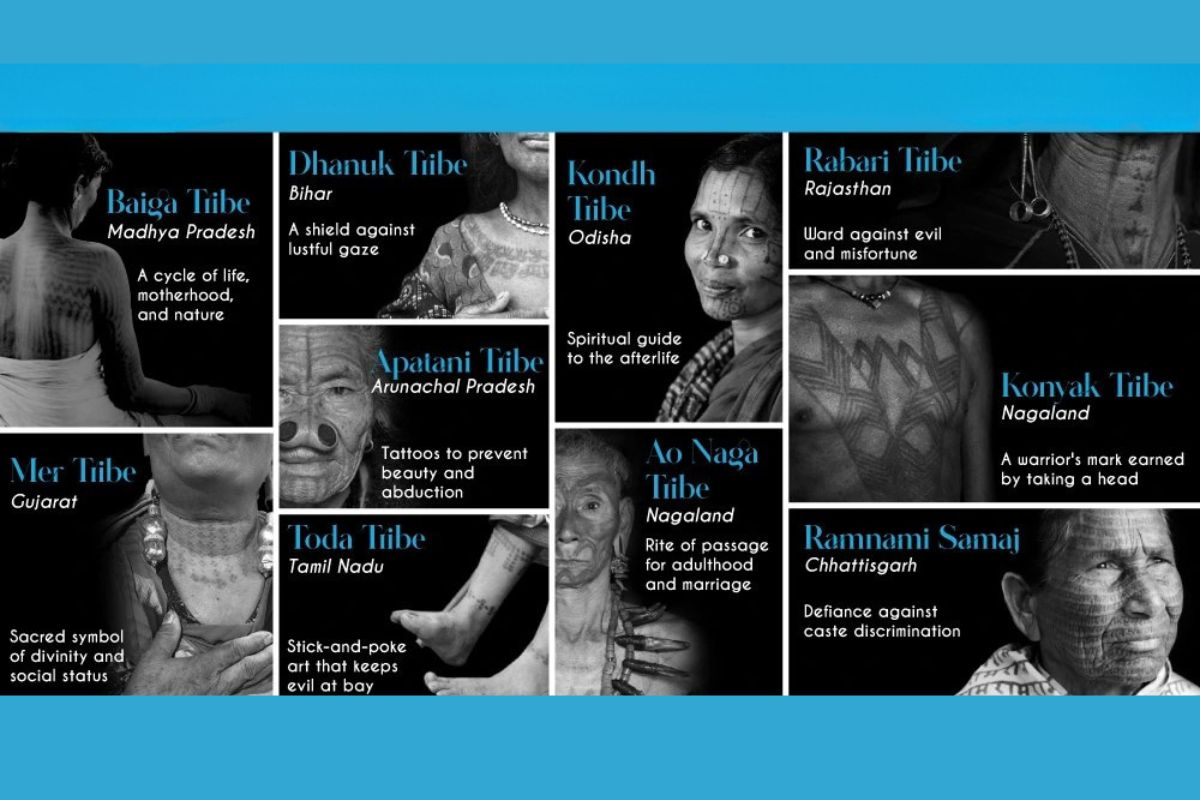

For example, the Baiga tribe from the central India, who is a literally forest dweller, uses tattoo to denote the identity and the stage of life. The first tattoo is engraved when a girl is nine years old, others are marked when the girl enters puberty, marries and when she gives birth. All of them entail privileged semantic significance, which sets one group apart from another. Sensitively, Rabari women of Gujarat have been utilising tattooing art as aesthetic and curative for centuries.

The Baiga tribe in particular starts tattoo practises when children reach five years of age for tattooing. The art designs of each tribe differ significantly from one another with specific patterns that display tribal affiliation. The tribal people found these markings important to maintain tribal identities during their commercial and social encounters. The traditional practices encounter the danger of disappearance as recent generations choose urban locations for their studies above maintenance of traditional values. Cultural preservationists alongside certain tribal youth groups work to document vital traditions while continuing their practice since these communal practices represent important cultural heritage instead of abandoned customs.

Ink & Identity: The Sacred Art of Pain

Getting traditional tribal tattoos applies an altogether different process compared to modern-day tattoo studio procedures. “The pain is part of the journey,” says, a tattoo artist from the Gond tribe. “It transforms the person, marking not just their skin but their spirit.” Traditional tattooing requires homemade instruments such as thorns attached to wooden sticks as well as small metal needles bound to these wooden contraptions. The tattoo ink derives from natural origins through combinations of soot in mother’s milk, plant extract ingredients and turmeric paste boiled with animal bile. People perform these ink injection rituals together with religious ceremonies that convert what society views as optional surgery into sacred social ceremonies.

The members of Kutia Kondh tribe in Odisha give young girls their face tattoos during designated community celebrations. Elders use traditional songs during sarnpad period to help participants cope with their pain and the visiting community attends to observe this ceremonial moment. Residents consider undergoing pain as a means to prove their character strength. “If you cannot bear this pain, how will you bear the pains of life?” Sukri Kashyap serves as an elder in Bastar who poses this inquiry to the author. Tribal members consider the tough method and subsequent fever and sickness to be essential hardship that serves as a training experience for their real-life challenges. The permanent marks function as more than cosmetics since they bridge physical discomfort to spiritual growth.

Tattoos as Markers of Identity: Symbols and Meanings

To the people of the tribe, tattoos are not mere ornaments; they are expression of the individuals’ identity within their tribal societies. According to the customs of the Baiga tribe, the forehead tattoos are very crucial in order to qualify to be a part of the tribe. That is why, members of that given community are not expected to have anyone outside of that community. This feeling is supported by other tribes such as the Apatani of Arunachal Pradesh and the Kutia Kondhs of Odisha.

The Apatani women follow BOTO practise which entails doing facial scarification called Tippei as well as wearing wooden nose plugs called Yaping Hullo. These were among the significant body arts used in the past to prevent marauders from kidnaping women, but they are now considered as indeed beautification and cultural expression. So, Kutia Kondh women, using charcoal and other things make geometric facial tattoos which make them recognisable in the spirit world after their death.

Every single line, spot, and curve used in the process of creating tribal tattoos has a strong meaning. “Nothing is random,” explains, an anthropologist who has studied tribal tattoos for decades. “These designs are a language written on skin.” In the case of the Toda tribe in Tamil Nadu, zigzags are the motifs for hills and mountains in which they reside while circles stand for unity and the cycle of their life. Tattooing among the Konyak Naga men was earlier linked with successful headhunters and though no longer practised, the tattoo reflects the cultural significance of the Konyak Naga men. The tattoos coven to women’s bodies mostly symbolise fertility, protection during births and also the situation of marriage. The members of the Ramnami community paint their skin with the name of Lord Ram, and thus their body is their prayer.

The Singpho tribe in Arunachal Pradesh also practises body tattoo to signify certain changes in their lives. “When a girl receives her tattoos, the community recognizes her as ready for womanhood,” says, a community leader. “For boys, tattoos mark their entry into manhood and responsibility.” These forms create some sort of picture that is hard to decipher by anyone fortunate enough to be an outsider. They are in fact capable of telling the history, ancestry, and spiritual beliefs of the native culture in an artistic and rather symbolic manner when the cultural meaning of such shapes and designs is not well understood. For the indigenous tribes, such marks become pen-forget-me-not etching of their identity, and they wake up each day with identity of who they are and where they come from.

Ink & Identity:Cultural Significance and Evolution of Tribal Tattoos Among Women

Preadolescent girls in several tribal societies are usually scarred more as compared to boys: these scarification marks or tattoos apart from being beautifying serve a multitude of other functions. An elder from the Santhal tribe states, “Our tattoos protect us in this life and the next,” highlighting the belief that facial tattoos shield women from evil spirits and enhance their fortune. For instance, the Apatani tribe of Arunachal Pradesh have stretched their earlobes and both men and women get tattoos on their face and they also wear large nose plugs which act as a seal with the intention to discourage the raiding parties from the neighbouring territories. In the material culture of Baiga women, the tattoos indicate important changes in their lives, namely, the transition to adulthood, marriage and motherhood.

As one woman reflects, “Each time the needle pierces our skin, we become stronger.” These tattoos are considered to serve a purpose of a shield whereas the overarching beauty portrayed of a woman is expected to fit the cultural norms and ideals of beauty. However, contemporary generations think over these vitalities suffering, tendered through TV advertisement or social networking sites. An elderly Baiga woman laments, “My granddaughters ask why they need these marks when they can wear beautiful clothes instead.” This antithesis of the traditional culture and the modern living culture is a transition period typical of the tribal women of today.

India tribal tattoos are philosophical in nature, some of the symbols seen in Indian tribal tattoos include the symbolic circle or oval which is the holy Om and the mandala symbolising unity of the universe. Tiger, snakes, birds, and other body paintings depict the native people and their harmony with the nature; looking at the Baiga tattoos which include mountains and moons on their body painting.

Ink & Identity: Fading Traditions

Multiple traditional practices followed by Indian tribes are disappearing as the country speeds up its path toward modernization. The tattooing customs stand as one of the practices facing the most endangered state. All residents of my village maintained tattoos back when I was a child. A Person from Jharkhand expresses sorrow about the fact that only ten elderly people now maintain their traditional body tattoos. Various elements lead to the reduction of this practice. The transition of tribal youth toward jobs in government agencies alongside formal education has resulted in their moving to cities where their traditional body markings encounter discrimination. The increased awareness in medical fields about traditional tattooing hygiene practices has become a matter of concern for people today. Christian missionaries have influenced tribal regions to fight against body tattoos as these practices represent pagan customs to them.

Young tribal members do not get tattoos because they are afraid of the severe pain that accompanies the practice. “My daughter refused when I suggested she get our traditional tattoos,” shares an lady from Maharashtra. “She says times have changed.” The dying numbers of artists who perform tattoos constitute one of the major challenges for tattoo traditions to survive. Crafting and teaching tattoo designs among the old masters of tattooing ends when they die without taking any apprentices. The study conducted by anthropologists indicates that out of the original 200 different Indian tribal tattooing customs only about 50 survive in the present day. Only the most distant communities who reside beyond urban reach continue to practise traditional heritage at present. “Each time an elder with tattoos dies, we lose a living page of our history book,” says cultural preservationist , who documents these practices through photography and interviews.

Ink & Identity: Revival and Modern Adaptations

The number of traditional tattoo practices declines while people increasingly embrace tribal tattoo revival but modify the traditional designs. “I understand why my grandchildren don’t want the traditional tattooing process, but they should still know what these symbols mean,” says , a Santhal elder. Various organizations seek to protect these art forms through modern initiatives. The Tribal Cultural Heritage Museum at Bhubaneswar protects tribal designs by using paintings along with photographic documentation methods.

The Hornbill Festival in Nagaland presents traditional body art, which artists create through contemporary secure tattoo practices. Modern tattoo artists residing in cities have started specializing in tribal tattoos by updating traditional styles for present-day clients using modern tattooing technology. “People come to me wanting to reconnect with their tribal roots,” explains , a tattoo artist from Manipur who specializes in traditional Naga designs. “I use modern needles and inks, but the symbols remain authentic.” Constraints about cultural appropriation versus appreciation emerge from these particular modifications.

The traditional symbols of tribal communities arouse fear among elders whenever non-tribal persons display them simply for fashion purposes. Some cultural members view present-day adaptations as needed transformations. “If our designs must change to survive, that is better than losing them altogether,” reasons , a Mizo cultural advocate. Some tribal youth have started getting modified versions of their traditional tattoos through smaller or discreet designs that either use modern methods or blend heritage symbols with contemporary fashion because they want to respect their culture and blend with popular society.

Ink & Identity: Skin as Living Canvas

The tattoo traditions described as the Indian tribes’ practices may seem more than mere body decoration; they are information stores recorded on the skin. Every one of them safeguards the relationship with the ancestors, the community, spirituality, and culture as a whole, without the need for descriptions. Due to the increased modernization processes, the identified traditions remain on a critical crossroad and are in a critical state. Will they be remembered merely in the historical books, documented only in museums and pictures or be transformed into something new and different that still pays homage to their previous form? “Our tattoos have always been about who we are,” reflects , an elder from the Maria Gond tribe. “Even as our lives change, our need to know our identity remains.”

The most interesting thing that can be observed in these traditions is that the human body is turned into what may be interpreted as a history in pictures. Unlike ink on paper, these scars remain on the body and can only be removed through the subject’s death, making them among the most personal media of art and culture conceivable. Although the art of carving might now slowly diminish, the need to punctuate life in various significant stages and assert ethnicity in regard to the skin’s aesthetics is still innate. This indicates that although the aspects may transform in some form, the concept of imitating the skin and drawing identity on it will be continued in other unique form in subsequent generations.

Also Read: Chandrika Srinivas: A Parai Player Breaking Barriers and Preserving Heritage

You can connect with DNN24 on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel.