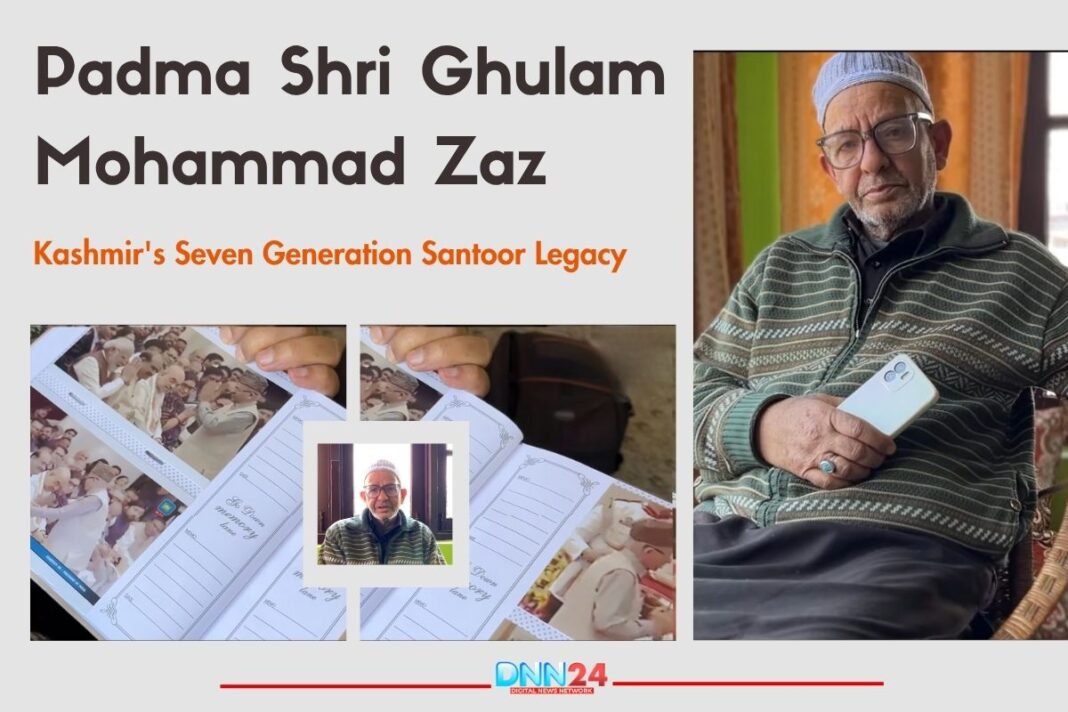

Along the banks of the River Jhelum in Srinagar’s Siraj Bazaar, a tradition older than memory itself continues to breathe. Ghulam Mohammad Zaz, now 78 years old, sits in the same ancestral workshop where his forefathers once sat, crafting instruments that have shaped Kashmiri music for eight generations. This is not merely a family business or an artistic pursuit. It is a covenant with history, a responsibility passed down through blood and devotion. The Zaz family home in Zaina Kadal has witnessed the birth of countless Santours, Sitar, Rabab, Sarangi, Dilruba, and Taus instruments, each one carrying the soul of Kashmir’s musical heritage.

When Ghulam Mohammad speaks of his ancestors, his voice carries the weight of centuries. His family never needed introductions in the world of classical music. Nawabs and royal families across India sought their instruments, not merely to play them but to treasure them as sacred heirlooms. Today, museums around the world display instruments crafted by the Zaz family, standing as silent witnesses to a legacy that refused to fade. At an age when most people rest, Ghulam Mohammad continues to work with wood, wire, and devotion, knowing that he may be the last keeper of this ancient flame.

Padma Shri Ghulam Mohammad Zaz:The Craft That Built Kingdoms

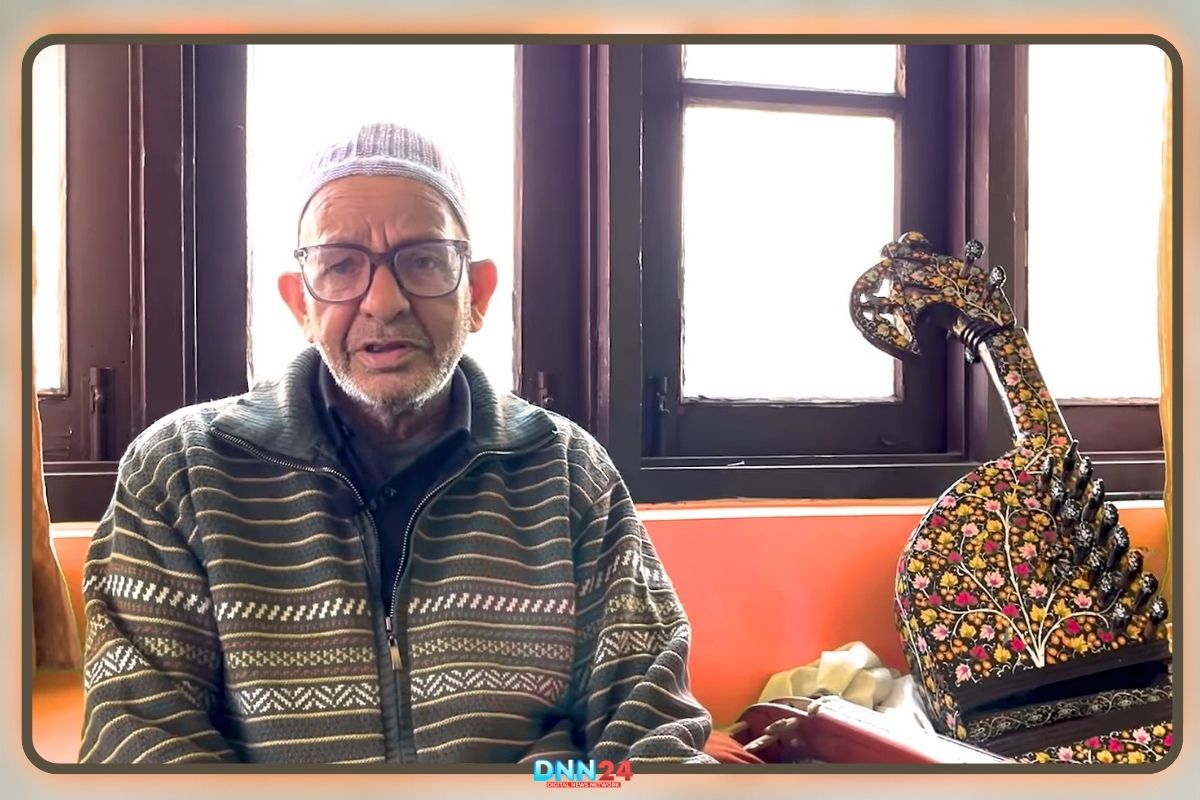

The instruments created by the Zaz family were never ordinary. Ghulam Mohammad explains that his ancestors were masters of all stringed instruments, not just the Santoor. They crafted Kashmiri Sitars, Saazis, dilruba, Taus, Surbahar, Indian Sitars, and Tanpuras with equal skill and precision. Each instrument required months, sometimes years, of careful work. The wood had to be selected from specific trees in the forest, cut at the right time, and then seasoned for months or even years before it could be shaped. The process demanded patience, knowledge, and an almost spiritual understanding of how wood and metal could be transformed into music.

What made the Zaz instruments special was not just technical skill but something more profound. The family worked in an atmosphere steeped in Sufi tradition, where music was not entertainment but a path to the divine. Elderly Sufi mystics would visit the workshop, and their blessings seemed to infuse the instruments with something beyond craftsmanship. Ghulam Mohammad attributes his family’s success not to their own hands but to the prayers of these holy men and the grace of God. This humility runs through his words like a quiet river, never demanding attention but always present.

Padma Shri Ghulam Mohammad Zaz : From Sufi Gatherings to Concert Halls

The Santoor itself tells a story of transformation. Initially, the instrument was played in traditional Kashmiri style at Sufi gatherings, where wealthy and respected elders would listen to devotional music. These were not performances in the modern sense. They were spiritual assemblies where the recitation of divine verses took precedence over musical virtuosity. The Santoor accompanied these recitations with gentle, meditative tones that supported rather than dominated the experience. Then came the revolution. Two musicians from Kashmir changed everything. Pandit Shiv Kumar Sharma from Jammu and Bhajan Sopori brought the Santoor out of its traditional context and into the world of Indian classical music.

Shiv Kumar Sharma, after learning the instrument in Kashmir, moved to Bombay and introduced it to the film industry. His unique approach gave the Santoor a new voice, one that could speak to modern audiences while retaining its classical dignity and elegance. The government recognised his work and sent him abroad as a cultural ambassador. Bhajan Lal Sopori also played a crucial role, though his style remained more traditional. The combined effect of their efforts was remarkable. An instrument that had been confined to intimate spiritual gatherings suddenly gained widespread recognition across India and beyond, its haunting tones resonating with audiences who had never encountered Kashmir’s musical traditions.

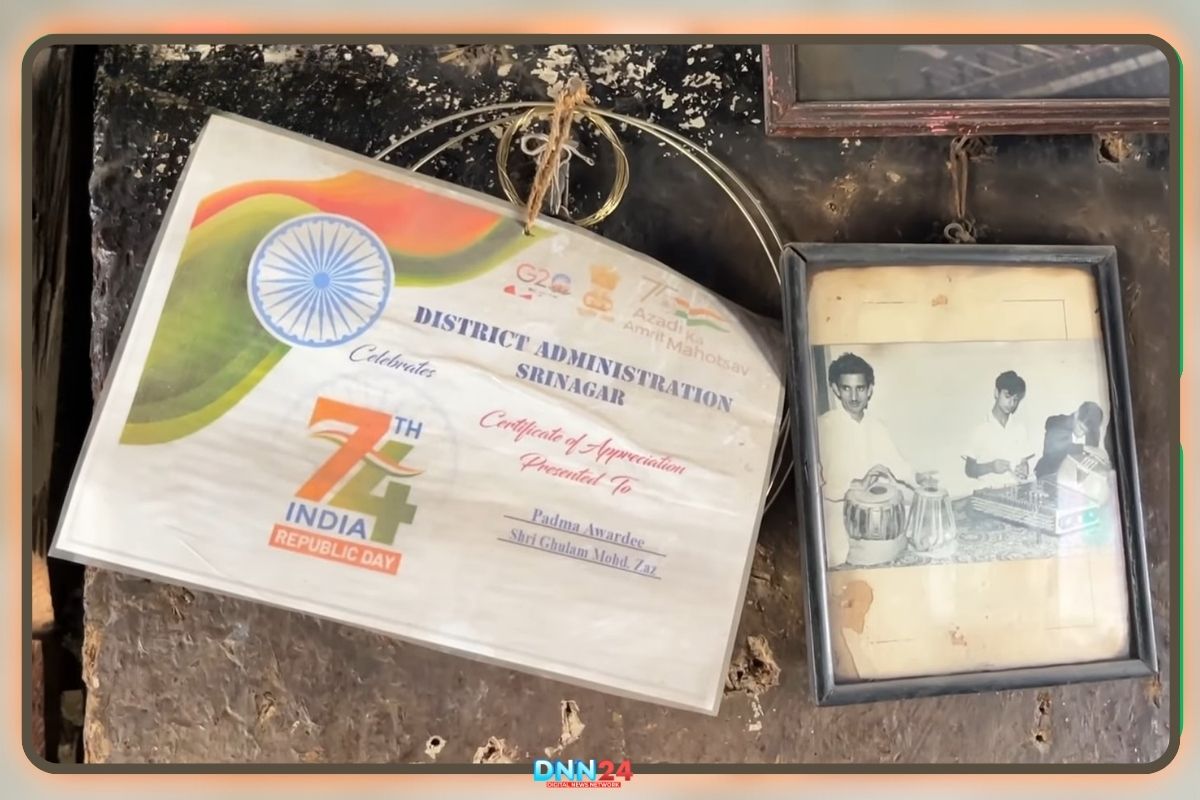

The Padma Shri and the Weight of Ancestors

When Ghulam Mohammad Zaz received the Padma Shri award, he did not celebrate it as a personal achievement. Instead, he felt the presence of his ancestors, particularly his father and grandfather, whose names should have been honoured decades earlier. The workshop still operates under the name Rahman Zaz and Sons, a tribute to his grandfather’s reputation. Ghulam Mohammad sees himself as merely the seventh or eighth link in a chain that stretches back into history. He is a student of students, carrying forward knowledge that was never written down but passed through observation, practice, and quiet correction.

The award, he insists, belongs to those Sufi elders who blessed the family’s work, to the generations who perfected the craft, and ultimately to God’s grace. This perspective reveals something about traditional craftsmanship that modern culture often misses. For Ghulam Mohammad, skill is not an individual genius, but rather collective wisdom accumulated over centuries.

He never studied at any formal institution or learned from outside teachers. His education came from watching his father and uncles work from dawn until dusk, from being asked to hand them tools as a small child, and from breathing in the atmosphere of creation every single day. The workshop was at his school, and the lessons were absorbed naturally, just like a child learns a language.

Padma Shri Ghulam Mohammad Zaz: The Question That Haunts the Workshop

Despite his continued dedication, Ghulam Mohammad faces a question that troubles him deeply. He is now 78 years old, working with hands that have shaped instruments for over six decades. But what happens after him? The eighth generation may be the last. His children have their own lives, their own paths. The modern world offers opportunities that his ancestors could never have imagined, and the patient, time-consuming work of crafting traditional instruments may not appeal to the next generation. This uncertainty weighs on him. The wood stored in his workshop has been ageing for years, sometimes decades.

His ancestors cut some pieces and have been waiting patiently for the right moment, the right instrument. He knows which type of wood suits each instrument, how long it needs to season, how to read the grain, and how to predict its response to tension and vibration. This knowledge cannot be learned from books or videos.

It comes from years of intimate contact with materials, from countless small failures and adjustments, from a lifetime of attention. If this knowledge dies with him, something irreplaceable will be lost. Yet Ghulam Mohammad continues working. As long as breath remains in his body, he says, he will keep crafting instruments. This is not stubbornness or denial. It is faith in the tradition itself, a belief that what is truly valuable will find a way to survive.

The Music That Refuses to Die

Ghulam Mohammad Zaz represents more than personal achievement or family pride. He is a living bridge between Kashmir’s past and an uncertain future. In his hands, wood becomes music before it ever produces a single note. The instruments he creates carry within them the prayers of Sufi mystics, the dedication of seven generations, and the soul of a culture that has survived countless upheavals. When the Santoor resonates in concert halls around the world, when the Rabab accompanies traditional songs, and when the Sarangi weeps its ancient melodies, the work of the Zaz family speaks.

Their legacy exists not only in museums but in every note played on the instruments they crafted. Ghulam Mohammad’s story prompts us to reflect on what we value and what we are willing to preserve. In an age of mass production and instant gratification, his patient devotion to excellence seems almost revolutionary.

His workshop by the Jhelum stands as a reminder that some things cannot be hurried, that true mastery requires a lifetime, and that the most significant achievements often come from serving something larger than oneself. Whether the ninth generation will continue this work remains to be seen. But as long as Ghulam Mohammad Zaz sits in his ancestral workshop, surrounded by ageing wood and the ghosts of master artisans, the music of Kashmir’s heritage continues to live.

Also Read: Sir Syed Ahmad Khan Built India’s Greatest University Through Sacrifice

You can connect with DNN24 on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel.