On 26 January 1950, India did not just mark a date on the calendar. It handed itself a fresh identity. That first Republic Day carried none of the polish we see now, no live television drama, no carefully timed flypasts cutting through the sky. It was quieter, smaller, almost humble. Yet in that simplicity lay something powerful: a nation deciding, for the first time in centuries, to govern itself by rules it had written in its own hand.

The Gap Between Freedom and Self-Rule

Freedom arrived at midnight in August 1947, wrapped in relief and sorrow. The British left, but they also left behind a question that would not go away: who decides how this country will be run, and under what law? For nearly three years after that midnight, the Constituent Assembly sat in long, tense sessions, turning over every word, every clause, every principle. Dr B. R. Ambedkar led the drafting, but hundreds of voices joined the debate. They were not simply copying laws from other nations. They were trying to stitch together justice, liberty, equality and fraternity in a way that could hold a vast, wounded, impossibly diverse land without tearing at the seams.

The Constitution was finally adopted on 26 November 1949, but it would not take effect for two months. The date chosen was deliberate: 26 January 1950. Twenty years earlier, on 26 January 1930, the Indian National Congress had declared Purna Swaraj, complete independence, as its goal. That declaration was a promise made in defiance. The date in 1950 was the fulfilment of that promise, now written into law. On that Thursday morning, the office of the Governor General, the last visible thread tying India to the Crown, dissolved quietly. In its place stood the office of the President of India, an office born not from conquest or inheritance, but from the will of the people.

A Ceremony That Held Its Breath

Picture Durbar Hall at Government House in New Delhi, the building we now call Rashtrapati Bhavan. It is 10:18 in the morning on 26 January 1950. The hall glows under chandeliers, packed with senior leaders, judges, diplomats, and military officers. But despite the crowd, there is a strange hush, as if everyone present can feel history moving through the room. C. Rajagopalachari, the last Governor General, stands at the centre and reads the proclamation: India, that is Bharat, is now a Sovereign Democratic Republic. Six minutes pass. Dr Rajendra Prasad steps forward and takes the oath as the first President of India. Outside, a 31-gun salute echoes across the city, announcing the birth of the Republic.

No smartphones are recording the moment, no instant updates flashing across screens, no hashtags trending by lunchtime. The ceremony is solemn, careful, almost fragile. But in that careful tone lies a quiet triumph. A country that had been ruled for centuries by others has now given itself its own highest law. Somewhere beyond the walls of Government House, life continues as usual. Shopkeepers open their shutters. Children chase kites through narrow lanes. Most of them do not yet know that, on paper at least, they now live under a Constitution that promises them rights, dignity and a voice.

The First Parade Was Nothing Like Today

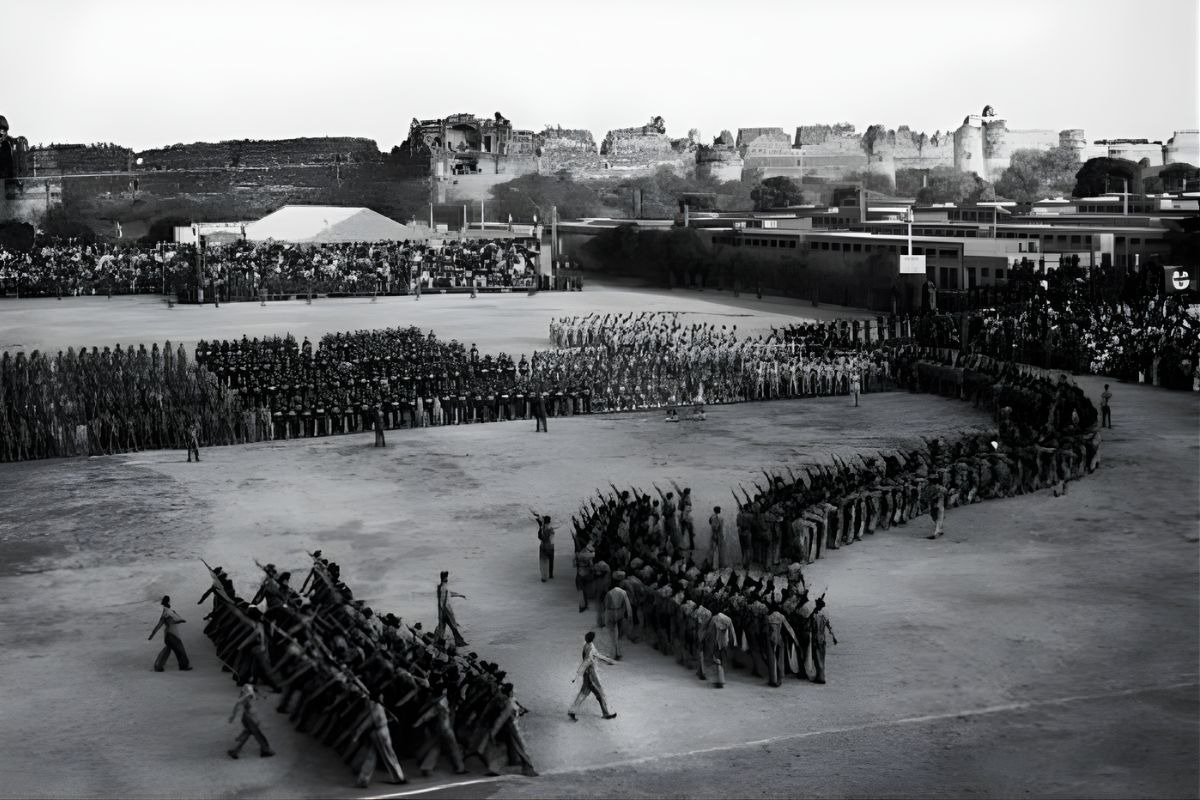

When we think of Republic Day now, we see Kartavya Path stretching wide, tableaux rolling past in bright colours, fighter jets roaring overhead, and crowds pressed against barriers for hours. But 1950 looked entirely different. The main parade that year was not held on Rajpath at all. It took place at the Irwin Amphitheatre, the ground that is now known as the Major Dhyan Chand National Stadium.

In the afternoon, Dr Rajendra Prasad rode through Delhi in a carriage, waving to cheering crowds along the route. He reached the stadium around 3:45 in the afternoon. There, before nearly 15,000 spectators, about 3,000 officers and men from the armed services and police stood in formation. Massed bands played. The tricolour rose slowly over the stadium. It was one of the most impressive military displays the young nation had managed to organise. Still, it lacked the technical precision and grand choreography we expect today. Instead, it had something rawer, something more uncertain: a new confidence trying to find its feet.

Across the country, Republic Day was observed not with spectacle but with small gestures. Flags were hoisted in village squares. Sweets were distributed in schools. Children were told, in simple terms, that this country now belonged to them, that they had rights written down in a book called the Constitution. Seen from the distance of 2026, that first Republic Day feels almost intimate, like watching someone take their very first steps in public, wobbly but determined.

What That Day Still Whispers To Us

More than seven decades later, Republic Day has become routine for many of us. Another holiday. Another parade on television. Another morning spent half watching the screen while scrolling through messages. But if we pause and listen closely, that first Republic Day in 1950 is still speaking to us, quietly but clearly. The Constitution that came into force that morning was not just a legal document. It was a contract between the state and its people, a promise that justice, liberty, equality and fraternity would not remain distant ideals but would take shape in laws, courts, elections and everyday life.

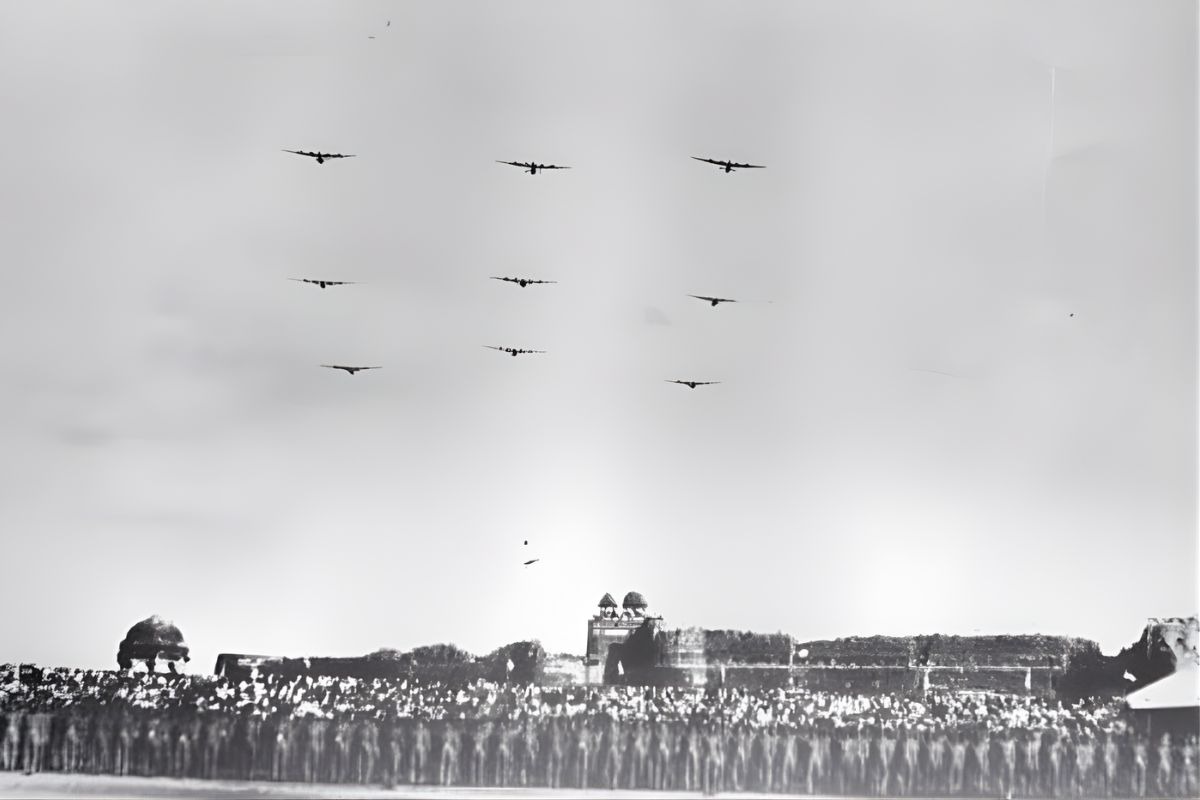

That contract came with a condition, though. It asked us to behave not as subjects or spectators, but as citizens. Every time we debate rights and responsibilities, argue about new laws, protest injustice or celebrate inclusion, we are, in a way, still standing in that Durbar Hall, still deciding what kind of Republic we want to be. The stadium parade of 1950 has grown into a massive display on Kartavya Path, complete with advanced aircraft, elaborate cultural tableaux and dignitaries from around the world. But beneath all the colour and noise, the core question remains the same: are we living up to the promise we made to ourselves that morning?

In 2026, when we watch the flypast or share a Republic Day greeting, we are not simply remembering a date. We are checking the mirror. We are asking whether the India that stepped out as a young, uncertain Republic in 1950 would still recognise the India we are building now. That question does not have an easy answer, but the fact that we keep asking it means something. It means the contract is still alive, still being negotiated, still worth fighting for. And perhaps that is the real legacy of that first Republic Day: not the ceremony itself, but the conversation it started. This conversation has never really ended.

Also Read:Saheli Women’s Revolution: When Needles Sparked Strength and Change

You can connect with DNN24 on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel.