High in the Western Ghats, where clouds brush against mountain peaks, and forests hold their breath, a narrow cleft between two massive boulders guards one of India’s most remarkable treasures. The Edakkal Caves of Wayanad, Kerala, are not caves at all but a dramatic geological split that became humanity’s ancient canvas. Here, perched 1,200 metres above sea level on Ambukutty Mala, Stone Age artists transformed rock walls into a gallery that still speaks across thousands of years.

A Hunter’s Accidental Discovery

The year was 1890. Fred Fawcett, a British officer tracking game through Wayanad’s dense wilderness, squeezed through a narrow opening between boulders. What greeted him stopped him cold. The rock walls surrounding him were alive with images: human figures frozen mid-hunt, animals captured in eternal motion, geometric patterns defying interpretation, and mysterious symbols that seemed to hint at forgotten languages.

Fawcett documented what he saw, and his published account set the scholarly world ablaze. This was no ordinary find. The petroglyphs covering these rock surfaces represented South India’s finest Neolithic art gallery, with some engravings potentially dating back to 6,000 BCE or earlier. Only the Mesolithic rock art at Shendurney could claim similar antiquity in the region.

The physical space itself commands attention. This natural fissure stretches 96 feet in length and 22 feet in width, sheltered by a massive overhanging boulder that serves as a roof. The wedged formation gives Edakkal its name, which translates from Malayalam as “stone in between.” Nature created the stage; ancient humans provided the performance.

Layers of Time Written in Stone

Modern archaeological investigation has revealed that Edakkal tells not one story but many. The rock walls contain over 400 distinct motifs, created across multiple eras. The oldest layer screams of Neolithic life: hunters drawing their bows, dancers caught in ritual trance, elephants trumpeting across the stone surface. These core engravings offer raw glimpses into the daily existence of people who called these mountains home between 8,000 and 10,000 years ago.

A second layer adds megalithic elements from around 1,000 BCE, the Iron Age bringing new artistic sensibilities. Pottery fragments and nearby dolmen burial sites confirm continuous human presence over the centuries. The Wayanad Heritage Museum now houses earthenware and tools excavated from the surrounding areas, physical proof of the communities that thrived here.

The most intriguing discovery came through careful analysis of specific motifs. One particular carving shows a human figure holding what appears to be a jar or cup. Historian M.R. Raghava Varier identified striking similarities between this image and seals from the Indus Valley Civilisation. The implications were staggering: had Harappan traders travelled ancient routes connecting Mysore to the Malabar ports, bringing their cultural influences deep into the southern hills?

This connection between the Indus Valley and Edakkal suggests that Dravidian culture did not emerge in isolation. Ideas, goods, and artistic traditions flowed along mountain trade routes. Scholar Iravatham Mahadevan called the findings a significant discovery, evidence that bridges India’s northern and southern prehistoric worlds. The Indus civilisation did not simply vanish; its cultural echoes travelled south, blending with local traditions.

The carvings themselves reveal daily life in stunning detail. Hunters armed with spears stalk deer across the rock face, survival captured in careful lines. Female figures with flowing hair might represent priestesses invoking rain or fertility. Wheels suggest early transportation technology. Unknown scripts tease at languages that died before writing systems could fully preserve them. Animals populate the stone gallery: tigers prowling, cattle grazing, serpents coiling in patterns that likely held symbolic meaning. Tools appear repeatedly: axes for clearing forest, pots for cooking and storage.

Where Myth Meets Memory

Local tradition wraps Edakkal in an epic narrative. According to Ramayana lore, Lava and Kusha, the warrior sons of Lord Rama, fired arrows at demons terrorising the region. One arrow struck with such force that it split the mountain, creating the dramatic cleft. Another legend credits Kuttichathan, a beloved trickster spirit in Kerala folklore, with hurling a boulder at the goddess Mudiampilly, the stone lodged between the existing rocks, creating the eternal shelter.

These stories, passed down through generations, root Edakkal in the living religious landscape. Locals still make pilgrimages to Ambukutty Hills to honour the deities associated with this sacred space. The legends humanise the geological formation, transforming scientific fact into cultural memory.

Archaeological dating confirms the artistic timeline. The oldest engravings form the core, followed by Neolithic expansions, then megalithic refinements on the outer edges. Some researchers have even identified a 5th- to 6th-century Prakrit Grantha inscription attributed to Vishnuvarman, a Kadamba king, proving that Edakkal remained culturally significant well into the historical period. This continuous occupation spanning thousands of years makes Edakkal unique among Indian archaeological sites.

Preservation and Presence in Modern India

Today, Edakkal functions as both an archaeological site and an active pilgrimage destination. Visitors climb 600 stone steps through spice plantations and dense forest to reach the cleft. The trek itself becomes part of the experience, the physical effort connecting modern travellers to the countless generations who made similar journeys.

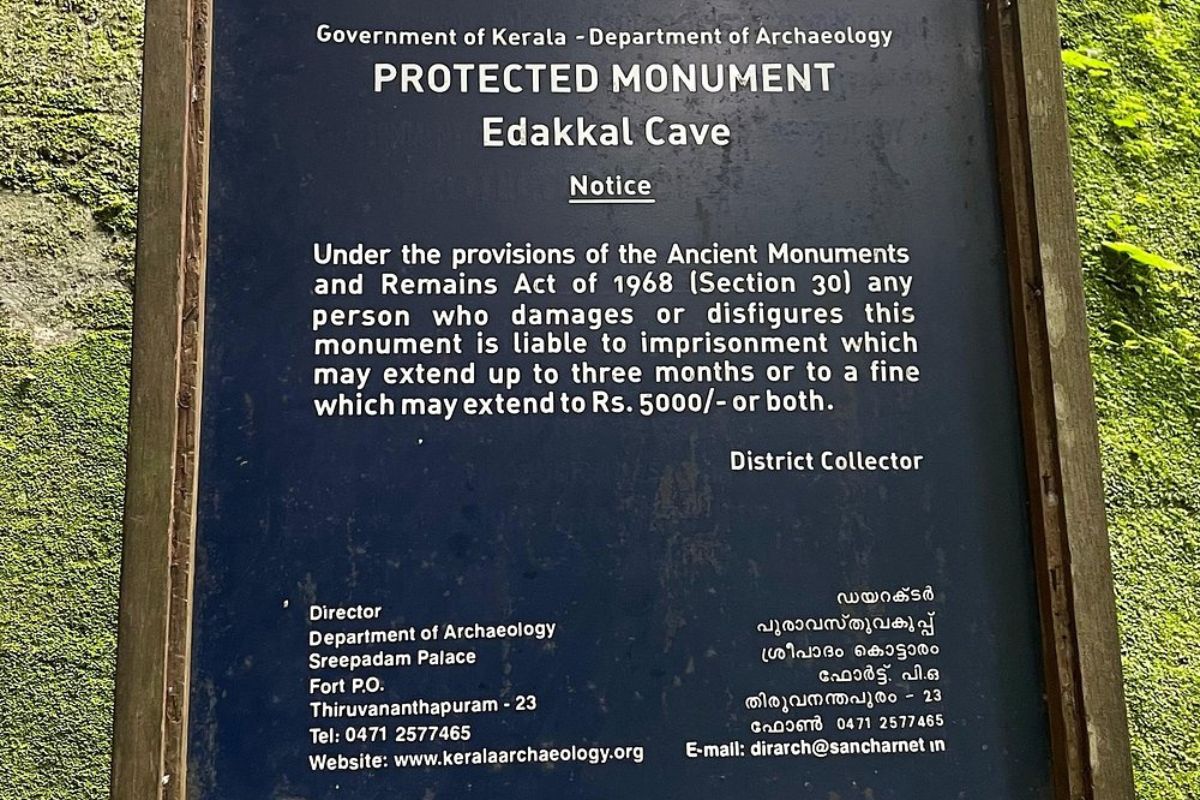

The Archaeological Survey of India and Kerala’s archaeology department work to protect the site while allowing public access. Daily visitor numbers are capped at 1,920 to minimise wear on the ancient carvings. Guides trained in the site’s history lead tours, helping visitors understand the significance of specific motifs. Entry fees remain modest, making Edakkal accessible to students, researchers, and curious travellers alike.

From the vantage point of the rock shelter, the Wayanad landscape unfolds in dramatic panoramas. Valleys stretch below, forests spread to distant horizons, and on clear days, wildlife can be spotted moving through the greenery. The view reminds visitors why ancient peoples chose this location: it offered not just shelter but command of the surrounding territory.

Recent years have brought both challenges and innovations. The 2024 landslides that devastated parts of Wayanad forced temporary closures as authorities assessed structural stability and cleared access roads. Local communities rallied to restore pathways and ensure the site could safely reopen. This resilience mirrors the endurance of the carvings themselves.

Conservation faces ongoing threats. Monsoon rains gradually erode exposed rock surfaces. Increased tourist traffic, while economically beneficial, risks physical damage to the petroglyphs. Climate change introduces new variables: temperature fluctuations, altered rainfall patterns, and potential seismic activity. Environmental organisations have highlighted these modern perils, arguing that contemporary threats may prove more destructive than the thousands of years of natural weathering the site has already survived.

Cultural Bridge Across Centuries

Edakkal’s significance extends beyond archaeology into questions of identity and continuity. The site demonstrates that sophisticated artistic traditions flourished in South India during periods often overlooked in mainstream historical narratives. The possible Indus Valley connections challenge simplistic models of cultural diffusion, suggesting a complex web of interaction across the subcontinent instead.

Educational programs now bring school groups to Edakkal to teach young Indians about their deep heritage. The Wayanad Heritage Museum has expanded its exhibits, using pottery fragments, tool replicas, and detailed photographs to contextualise the rock art. Tourism development has brought economic opportunities to the surrounding villages. Homestays offer visitors comfortable accommodation while providing income to local families. Women from nearby communities have trained as official guides, gaining employment while sharing their knowledge of the site.

The physical act of visiting Edakkal carries particular resonance. As global changes accelerate, these ancient rock carvings offer perspective. The hands that carved these images faced their own uncertainties: changing climates, resource competition, cultural transformation. They responded by creating art that would outlast their individual lives, sending messages across millennia.

Edakkal also raises urgent questions about responsibility. If these carvings survived 8,000 years or more, what obligation do current generations bear to ensure their survival? The answer requires balancing access and preservation, economic development and environmental protection, local needs and global heritage values.

As visitors descend from Edakkal, stepping carefully down the stone pathway through mist and forest, they carry something intangible but tangible: a renewed sense of human continuity. The artists who transformed these rock walls were not so different from us. They observed their world, valued beauty, sought meaning, and hoped to leave something lasting behind. Edakkal Caves endure as a testament to creativity, persistence, and the deep human need to make marks that matter. In the stone between stones, ancient voices whisper still.

Also Read: Gudibande Fort: Where Stone Walls Still Guard Ancient Water Secrets

You can connect with DNN24 on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel.