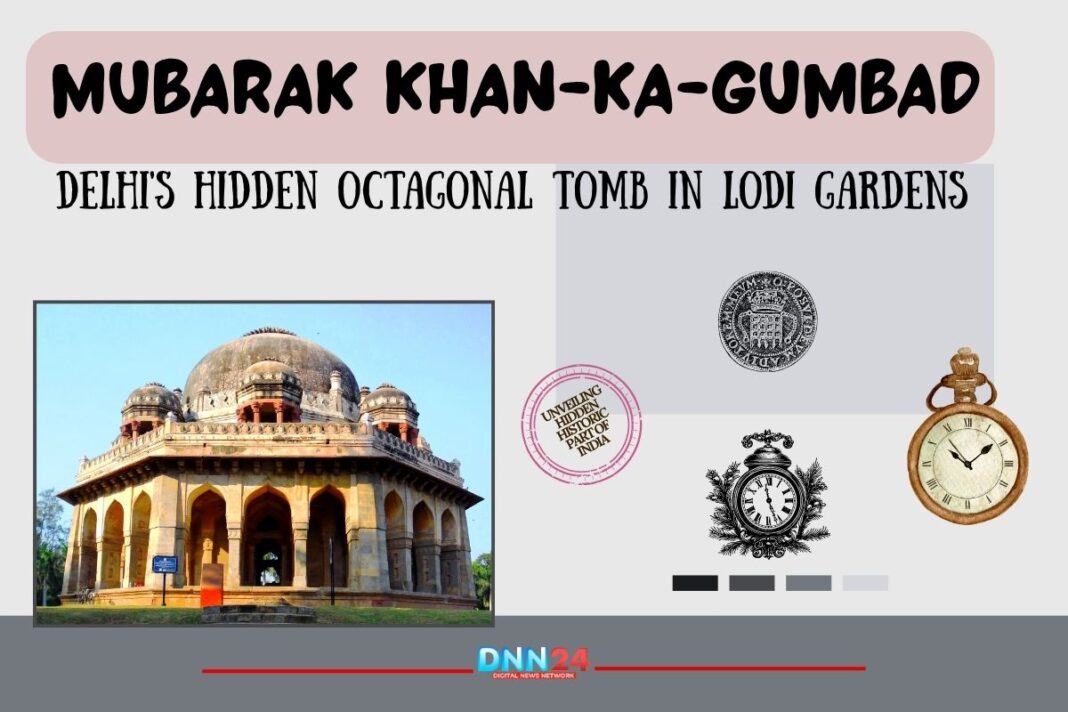

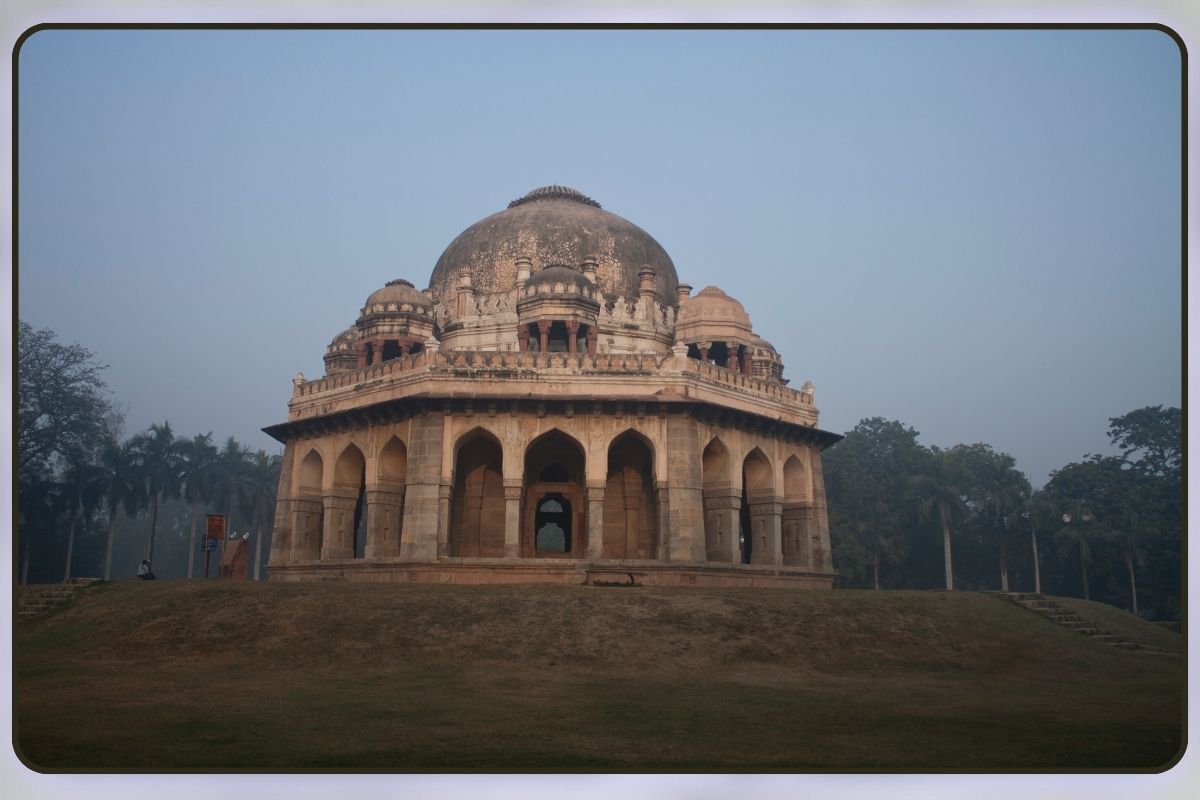

In the middle of Delhi’s famous Lodi Gardens stands a beautiful octagonal structure that most visitors walk past without knowing its remarkable story. This is the Mubarak Khan-ka-Gumbad, also known as the Tomb of Mohammed Shah Sayyid, a monument constructed in 1444 during one of Delhi’s most challenging periods. Mohammed Shah was the third ruler of the Sayyid dynasty, and his life was far from easy. He came to power after violent palace murders and inherited an empire that barely extended beyond Delhi’s walls. His enemies called him weak and pleasure-loving, but his son Alauddin Alam Shah wanted the world to remember his father differently. So he built this tomb, an octagonal wonder that speaks of love and respect even when money was scarce and enemies were many.

The Sayyid dynasty was collapsing, but this monument shows that even in decline, people can create something worth remembering. The tomb is not grand like the Taj Mahal or massive like Humayun’s Tomb, but it carries an exceptional quality. It was built with limited resources yet shows great artistic skill. The structure combines Islamic architectural traditions with local Indian design elements, creating a unique feature in Delhi’s landscape. Today, joggers pass it every morning, children play on its steps, and photographers capture its beauty during golden hour. Still, few stop to think about the struggling king whose memory it preserves and the son who refused to let his father be forgotten.

Mubarak Khan-ka-Gumbad: The Architecture That Tells a Thousand Stories

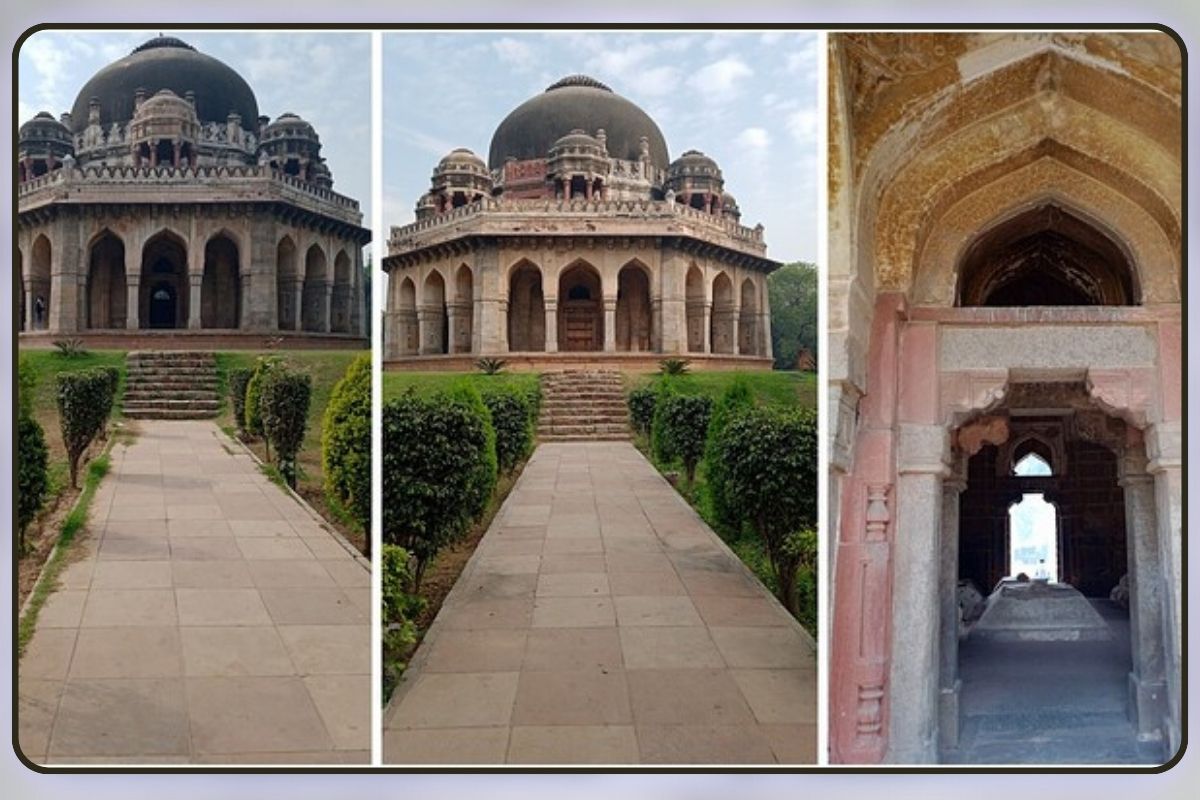

The tomb’s octagonal shape makes it stand out among Delhi’s many monuments. Eight sides rise from a raised platform, each decorated with care and attention. Around the central dome sit eight smaller domed pavilions called chhatris, each topped with lotus-shaped finials that show Hindu influence on Islamic architecture. The pillars are made from Delhi quartzite, a strong stone that has survived nearly six centuries of weather, wars, and neglect. Walking inside feels like entering a different world. The main chamber holds eight graves, with Mohammed Shah’s in the centre and seven others, probably family members, arranged around him. The walls carry intricate plasterwork with geometric patterns, floral designs, and bands of calligraphy.

Some original colours remain visible, touches of red, blue, yellow, and green that once covered much more of the interior. The Sayyid rulers had little money compared to earlier Delhi sultans, but they made every rupee count. The tomb shows a return to decorative architecture after the plain, fortress-like buildings of the Tughlaq period. The chhatris, the carved details, and the careful proportions all influenced later Mughal architecture. Experts say that this tomb helped inspire the design of Sikander Lodi’s nearby tomb and contributed ideas that eventually influenced Humayun’s Tomb and the Taj Mahal. The building proves that creativity does not need unlimited budgets. Sometimes the most memorable architecture emerges from working within limits, where every design choice matters because resources compel you to be thoughtful rather than extravagant.

Mubarak Khan-ka-Gumbad: A Monument That Survived Against All Odds

For nearly 600 years, Mubarak Khan-ka-Gumbad has stood in Delhi, watching the city change around it. The Sayyid dynasty fell, followed by the Lodis, then the Mughals, then the British, and finally, independent India. Through all these changes, the tomb remained, though not always in good condition. By the 20th century, the structure had begun to crumble. Cracks appeared in the walls, the decorative plasterwork was falling away, and rain was damaging the foundations. The Archaeological Survey of India and INTACH stepped in to save it. Restoration teams worked carefully to stabilise the structure, repair damage, and protect the fragile carvings. They brought back some of the lost colours and strengthened the dome.

Today, the tomb is situated within Lodi Gardens, one of Delhi’s most popular public spaces. Every day, thousands of people visit the gardens for morning walks, evening picnics, or to escape the city’s noise and bustle. Many stop at the tomb to rest in its shade or admire its beauty. Photography students come to capture its lines and shadows. Heritage walk groups listen to guides explain its history. School children run around it during field trips. The tomb has become an integral part of daily life for many Delhiites, yet it retains its dignity and historic significance. This balance between being a living public space and a protected monument is rare and valuable. The tomb reminds modern Delhi that the past is not separate from the present but woven into it, that history lives not just in books but in the stones we walk past every day.

Mubarak Khan-ka-Gumbad: Why This Tomb Still Matters Today

Mubarak Khan-ka-Gumbad teaches important lessons to anyone willing to listen. It demonstrates that dignity and beauty can coexist even during challenging times. Mohammed Shah’s reign was short and troubled; his kingdom was falling apart, and his reputation suffered, but his son still built him a memorial that has lasted centuries. The tomb proves that loving remembrance can outlive political power. It also demonstrates the richness of Indo-Islamic architecture, how Indian and Islamic design traditions combined to create something neither could have produced alone. The lotus finials, the octagonal plan, and the decorative patterns all demonstrate cultural exchange and artistic innovation, even during periods of political chaos.

For architecture students, the tomb is a textbook in stone, illustrating how limited resources can inspire creative solutions. For historians, it marks a significant transition period between the Tughlaq and Lodi dynasties. For ordinary visitors, it offers a peaceful spot to sit and reflect, a reminder that Delhi’s history extends deeper than textbooks usually convey. The monument stands as proof that even forgotten kings and collapsed dynasties leave lasting marks. Mohammed Shah Sayyid may not be remembered as fondly as Akbar or Shah Jahan, but his tomb still draws visitors, still inspires artists, and still anchors a corner of one of Delhi’s most beloved gardens. In this way, his son’s wish ultimately came true.

Also Read: Kovai Kulangal Padhukappu Amaippu: Ordinary Citizens Revived Coimbatore’s Dying Lakes and Rivers

You can connect with DNN24 on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel.