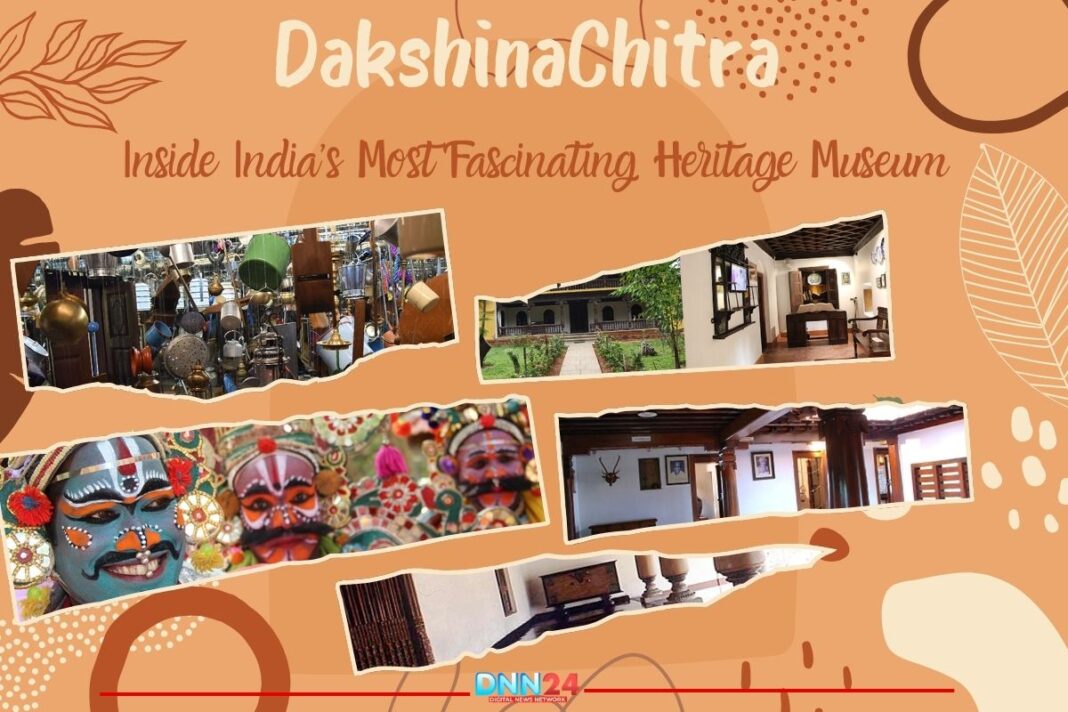

Standing at the gates of DakshinaChitra, visitors often wonder what lies beyond the traditional entrance. The answer transforms everything they thought they knew about museums.

A Museum That Breathes and Lives Beyond Glass Cases

DakshinaChitra breaks every rule about what museums should be. Forget dusty exhibits behind velvet ropes. This living museum near Chennai pulses with energy, where 18 authentic historical homes from across South India stand reconstructed on a sprawling ten-acre campus along the East Coast Road. Each structure tells stories of families who once lived within those walls, of artisans who shaped every beam and column, of traditions that survived centuries before finding sanctuary here.

The Madras Craft Foundation, guided by Dr Deborah Thiagarajan since 1984, opened these doors to the public in December 1996 with a revolutionary idea. Rather than letting beautiful vernacular architecture crumble into memory, why not save these homes from demolition and rebuild them precisely as they were? Traditional craftspeople, the Stapathis, dismantled each house piece by piece, transported the materials, and reconstructed everything with painstaking authenticity.

Visitors walk through actual Tamil, Kerala, Karnataka, and Andhra homes, touching walls that once sheltered real families, climbing stairs worn smooth by generations of footsteps. The museum preserves not just buildings but entire ways of life. Courtyards designed for monsoon rains, kitchens arranged for joint family cooking, sleeping quarters adapted to coastal humidity, every detail speaks of practical wisdom passed down through centuries. Children run through spaces their great-grandparents would recognise instantly, connecting the past and the present in ways no textbook ever could.

The Dream That Refused to Die in a Changing World

Dr Deborah Thiagarajan arrived in Chennai during the 1970s, an art historian from abroad who fell deeply in love with South Indian village life. She spent years researching in rural areas of Tamil Nadu, documenting crafts and architectural traditions. What troubled her kept growing worse. Modernisation swept through villages like a storm, demolishing old homes to make way for concrete boxes. Handicraft traditions faded as younger generations migrated to cities in search of different futures. Beautiful lime plaster gave way to cement, intricate woodwork disappeared under layers of paint, and centuries-old building techniques vanished with the artisans who knew them.

Most people would have written academic papers and moved on. Dr Thiagarajan refused to accept loss as inevitable. She founded the Madras Craft Foundation with a vision that seemed impossible to many. Preserving heritage required more than documentation or nostalgia. It demanded action, resources, and unwavering determination. The early years brought constant challenges. Funding remained scarce, bureaucratic obstacles appeared endless, and convincing traditional artisans to participate took patience and trust-building.

Many craftspeople felt hesitant about relocating their ancestral skills to an unfamiliar setting. Dr Thiagarajan persisted, often working behind the scenes, connecting people, raising awareness, and slowly building support. Her anthropological background helped her understand that preservation meant more than saving objects. Living traditions needed living contexts, spaces where crafts could evolve while staying rooted in authentic practice. That vision eventually crystallised into DakshinaChitra, a place where heritage doesn’t sit frozen in time but continues to grow and adapt.

Where Architecture Becomes Philosophy and Purpose

Laurie Baker’s name appears modestly in DakshinaChitra’s history, yet his influence runs through every corner of the campus. The legendary architect, known for championing sustainable building practices and local materials, contributed his expertise without charging a fee. Baker believed deeply that buildings should serve people and the environment rather than ego or fashion. His involvement ensured that DakshinaChitra itself embodied the values it sought to preserve. The master plan reflected Baker’s core principles. Use locally available materials, minimise environmental impact, and empower traditional builders rather than sidelining them.

He insisted that Stapathis, the hereditary master builders, should lead reconstruction efforts. These artisans possessed knowledge that no modern degree could replicate, understanding how wood responds to coastal moisture, how lime plaster breathes better than cement, and how traditional proportions create naturally comfortable spaces. Architect Benny Kuriakose joined the effort, supervising the careful reconstruction of heritage homes and designing public buildings that harmonised with vernacular structures. Together, Baker and Kuriakose created something rare in modern India.

DakshinaChitra became an architectural statement, proving that respecting tradition doesn’t mean rejecting progress. Visitors see buildings that work beautifully without air conditioning, walls that naturally regulate temperature, and courtyards that efficiently harvest rainwater. Every element teaches lessons about sustainable living that feel urgent today. The museum demonstrates possibilities rather than preaching ideology, showing how ancient wisdom offers solutions to contemporary problems. This architectural philosophy extends beyond aesthetics into ethics, celebrating craftsmanship and human-scale design over industrial standardization.

Where Tradition Dances Forward into Tomorrow’s Light

Walk through DakshinaChitra on any given day, and you encounter culture in motion. A potter shapes clay on a wheel while children watch, mesmerised. Folk musicians tune their instruments before an afternoon performance. Weavers demonstrate intricate techniques that transform thread into art. These aren’t staged displays for tourists but genuine exchanges where traditional knowledge passes to new hands. The museum runs extensive educational programs designed to make heritage accessible and engaging. Workshops invite participation rather than passive observation.

Visitors try their hands at kolam designs, experiment with natural dyes, and learn basic weaving patterns. This hands-on approach creates understanding that lectures never achieve. When someone struggles to generate even a simple clay pot, they gain instant respect for master potters who make it look effortless. Schools bring students for programs that connect classroom learning to living traditions. International seminars attract scholars and practitioners from around the world. The craft bazaars create marketplaces where rural artisans meet urban customers, helping sustain livelihoods that might otherwise disappear.

DakshinaChitra partners with Self Help Groups and NGOs, extending its impact beyond museum walls into communities where crafts still form daily life. Folk performers receive platforms that improve their skills and expand audiences. Rather than treating tradition as fragile and in need of protection from change, DakshinaChitra encourages innovation within cultural frameworks. What emerges is living heritage, not museum preservation. The museum’s work tells a larger story about resilience and hope. When Dr Thiagarajan began, the chosen site was called a sandy wasteland. Today, it blooms as a cultural haven where thousands gather annually to celebrate South Indian heritage. That transformation mirrors what happens when communities commit to preserving what matters while embracing necessary change.

Also Read: Truly Tribal: Hidden Village Art Revolution That’s Quietly Changing India

You can connect with DNN24 on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel.