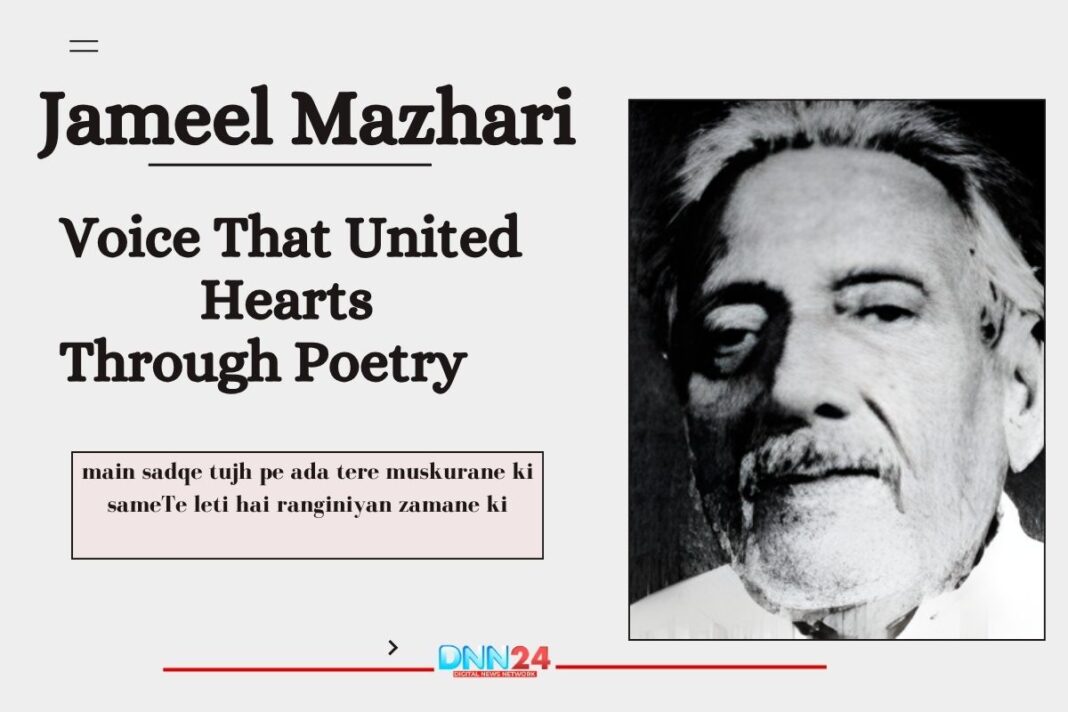

Syed Kazim Ali was born in 1904 in Patna, where books lined the shelves and poetry floated through the evening gatherings. His family believed in education the way some believe in medicine. They saw it as necessary, healing, and transformative. Young Kazim, who would later take the pen name Jameel Mazhari, grew up watching his elders recite Urdu and Persian verses after dinner. He listened carefully.

Jalane wale jalate hi hain charagh aakhir,

Jameel Mazhari

Ye kya kaha ki hawa tez hai zamane ki

By the time he was a teenager, he was writing his own poems, and they were of a high standard. Really good. His teacher, Wahshat, read them and found almost nothing to fix. That rarely happens with young writers, but Mazhari had something special. He understood rhythm. He understood pain. And he understood how to turn both into beauty. When he finished his Master’s degree from Calcutta University in 1931, India was restless under British control.

Hum mohabbat ka sabaq bhool gaye,

Jameel Mazhari

Teri aankhon ne padhāyā kya hai.

Students talked about freedom in hushed voices. Newspapers were censored. But education opened Mazhari’s eyes wider than any political speech could. He saw how power worked, how it crushed ordinary people, how it demanded silence. That awareness never left him. It seeped into his poetry like monsoon rain into dry earth. His writing became a place where sorrow met strength, where personal grief intersected with national struggle, and where faith posed challenging questions about justice and morality.

Hone do charaghan mahlon mein kya, humko agar Diwali hai,

Jameel Mazhari

Mazdoor hain hum, mazdoor hain hum, mazdoor ki duniya kaali hai.

When Courage Became Poetry

Jameel Mazhari did not write about bravery from a distance. He lived it. After university, he entered journalism and wrote articles that made people uncomfortable, the kind that authorities took notice of. In 1937, the Congress Party made him a publicity officer when they formed the government. It was a respectable position, stable, secure. But when 1942 arrived and the British government tightened its grip during the Quit India Movement, Mazhari faced a choice.

Kise khabar thi ki le kar charagh-e-Mustafavi,

Jameel Mazhari

Jahan mein aag lagati phiregi bu-lahabi.

He could stay silent and keep his job, or he could speak and lose everything. He chose the latter. According to stories passed down, he wrote his resignation letter using his own blood as ink. Whether entirely true or partly legend, the tale captures who he was. A man who would not pretend. After that, prison came. Hardship came. But so did poetry. His collections, such as “Naqsh-e-Jameel” and “Fikr-e-Jameel,” arrived during these difficult years.

Ba qadr paimana-e-takhayyul suroor har dil mein hai khudi ka,

Jameel Mazhari

Agar na ho ye fareb-e-paiham to dam nikal jaye aadmi ka.

His long poem “Masnawi Ab-o-Sarab” spoke about humanity’s thirst for meaning in a world obsessed with material gain. He wrote that people chase mirages while ignoring the real water nearby. After independence, he became a professor at Patna College. He could have rested then, enjoyed the stability.

Aaya ye kaun saya-e-zulf-e-daraaz mein,

Jameel Mazhari

Peshani-e-sahar ka ujala liye hue.

But Mazhari kept writing, kept questioning, kept feeling deeply. Even when Bombay’s film industry called him between 1945 and 1946, offering him work on films like “Kurukshetra” and “Baghawat”, he did not stay long. The glamour did not suit him. He returned to teaching, to simpler days, to students who needed guidance more than audiences required entertainment.

Inhi hairat zada aankhon se dekhe hain wo aansu bhi,

Jameel Mazhari

Jo aksar dhoop mein mehnat ki peshani se dhalte hain.

Building Bridges While Others Built Walls

India in the twentieth century saw terrible division between communities. Riots broke out. Neighbours became strangers. Fear replaced trust in many places. But Jameel Mazhari refused to accept this as usual. His poetry became a fragile yet real bridge between Hindus and Muslims. He believed in what people call Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb, that beautiful old idea that India’s cultures flow together like rivers, separate but mingling, creating something richer than either alone.

Buton ko tod ke aisa khuda banana kya,

Jameel Mazhari

Buton ki tarah jo ham shakal aadmi ka ho.

Mazhari did not just write about harmony. He practised it. He attended Hindu festivals, not as a guest keeping polite distance, but as someone who genuinely celebrated. He wrote poems about Diwali, about the lamps that push back darkness, about Holi and its colours that erase boundaries for a day. His home in Patna welcomed friends from all backgrounds. On Diwali nights, diyas burned in his windows too.

Ae sajda farosh-e-ku-e-butan, har sar ke liye ek chaukat hai,

Jameel Mazhari

Ye bhi koi shan-e-ishq hui, jis dar pe gaye sar phod liya

He once wrote in a letter that light does not check your religion before it illuminates your path. It just shines. For him, that was how people should be. In his poem “Ae Madar-e-Hindustan”, he sang about a country where hearts glow brighter than any festival lamp, where brotherhood is not a political slogan but a daily prayer.

Nahin afsoon hi ko afsane ki manzil maloom,

Jameel Mazhari

Galat aaghaz ka hota hi hai anjam galat

He studied Sufi mystics and Bhakti saints, those ancient voices that spoke of love crossing every boundary. They inspired him deeply. When people asked about his faith, he would say that genuine faith is love, and love cannot be divided by walls, rules, or fear.

Hasti hai judaai se uski, jab vasl hua to kuch bhi nahin,

Jameel Mazhari

Dariya mein na tha to qatra tha, dariya mein mila to kuch bhi nahin

A Legacy That Still Lights the Way

Jameel Mazhari passed away in 1980 in the city where he was born. He never married. He spent his salary helping widows, orphans, and students who could not afford books. In his last years, people saw him walking through Patna’s old neighbourhoods, sometimes carrying sweets during Eid, sometimes visiting Hindu families during Diwali. There is a story, probably true, about him helping rebuild a neighbour’s house after a fire destroyed it.

hamara to koi sahaara nahin hai

Jameel Mazhari

KHuda hai to lekin hamara nahin hai

The neighbour was Hindu. When someone asked why he did it, Mazhari reportedly said that faith only burns when humanity dies first. He won the Ghalib Modi Award in 1974, but prizes never changed him. He stayed quiet, modest, more interested in conversation than recognition. His poetry was melancholic but never without hope. It trembled with compassion for everyone, regardless of where they prayed or what language they spoke at home.

dariya ka chaDhaw dekhta hun

Jameel Mazhari

tinkon ka bahaw dekhta hun

Today, when India needs voices that unite rather than divide, Mazhari’s words matter more than ever. He proved that poetry can heal, that one person’s courage can inspire thousands, that kindness is not weakness but the hardest strength of all. Through decades of pain and beauty, struggle and grace, Jameel Mazhari became exactly what a poet should be. Not just a writer of pretty words, but a heartbeat of the nation.

Also Read: Bilqis Zafirul Hasan: The Poet Who Found Her Voice in Silence

You can connect with DNN24 on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel.