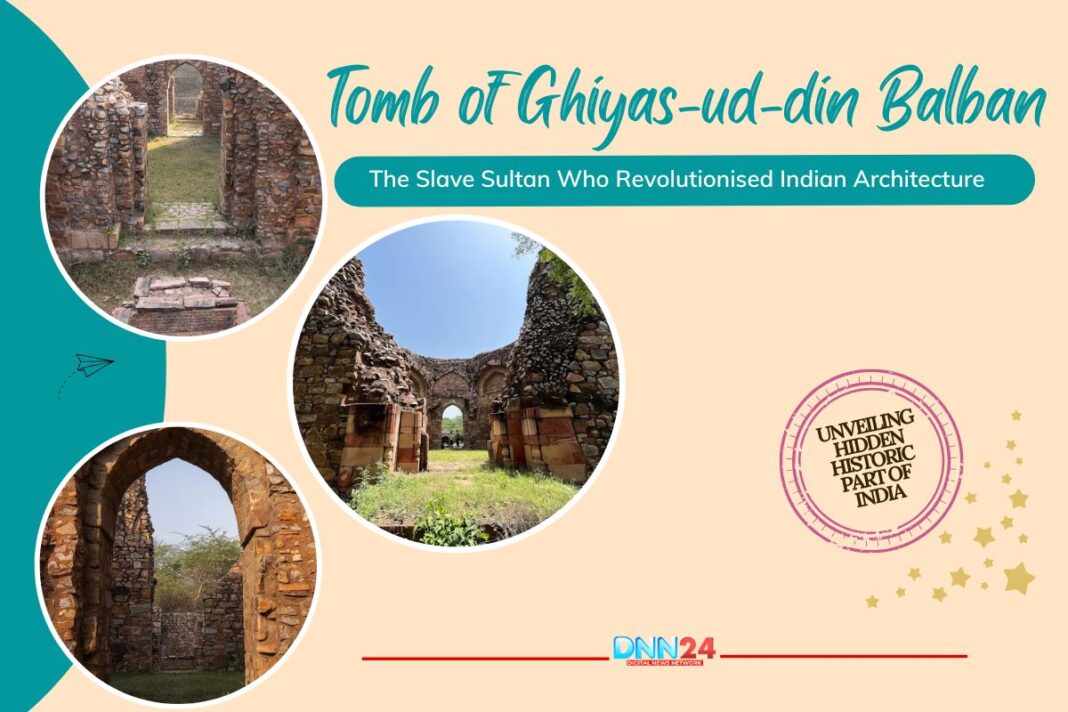

Walk through Mehrauli’s dusty lanes today, and you will find something extraordinary hiding among the wild grass and crumbling stones. The tomb of Ghiyas-ud-din Balban waits there, asking a question that most visitors never hear: how does a slave boy become the most powerful man in Delhi? This is not another decorated monument with marble screens and tourist crowds. This is raw history, stripped bare, telling a story that India has almost forgotten.

Between 1266 and 1287, Balban ruled Delhi with an iron grip, transforming a shaky kingdom into something resembling order. But before the crown, there was only a frightened boy in an Afghan slave market, purchased like cattle, dreaming of impossible things. His tomb carries no fancy inscriptions, no gold inlay, no elaborate carvings. Instead, it offers something rarer: honest stone speaking across seven centuries.

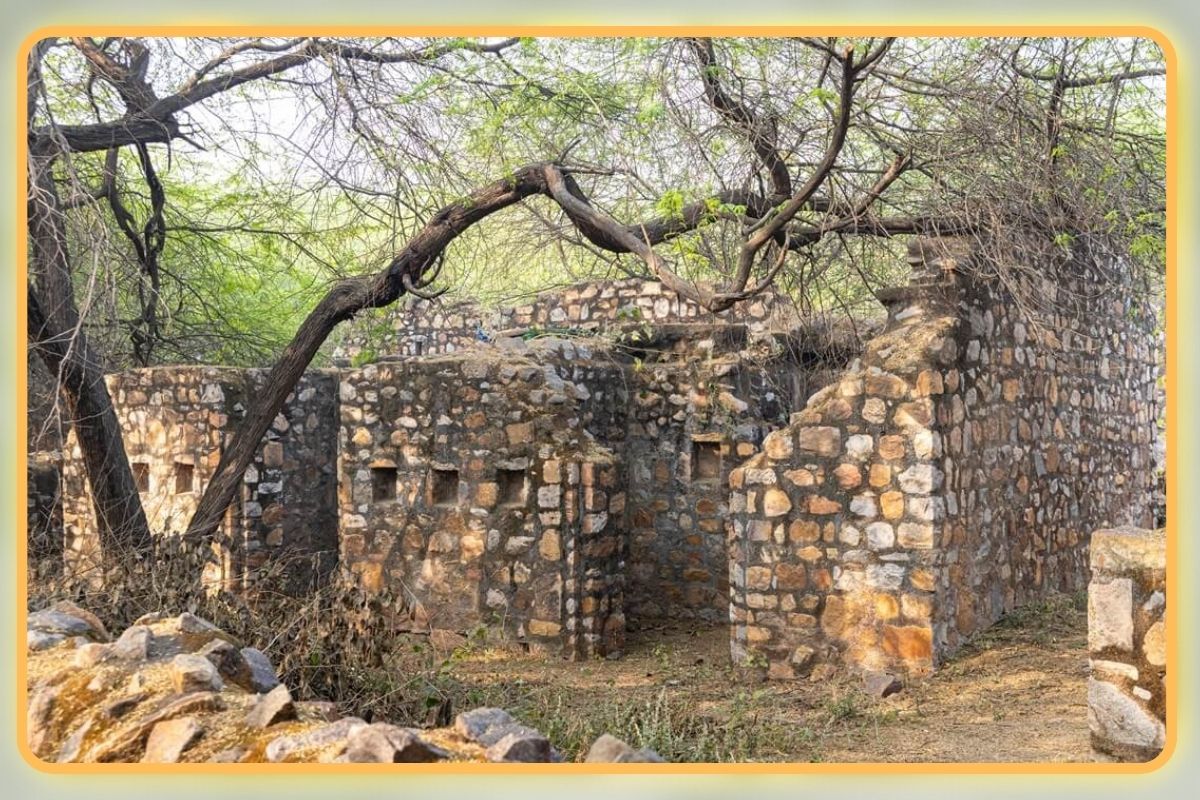

The structure stands roofless now, open to sky and rain, yet it refuses to disappear completely. Balban called this place Dar-ul-Amaan, the Haven of Safety, and perhaps he knew even then that safety is temporary, that power fades, but something deeper might survive. Today, this tomb teaches us what textbooks often miss about medieval India. It shows us that innovation does not always announce itself loudly. Sometimes the most revolutionary ideas wear the plainest clothes, waiting centuries for someone to notice what was always there.

Tomb of Ghiyas-ud-din Balban: The Arch That Rewrote Engineering Rules

Step inside these broken walls and look up at what remains. You are standing beneath India’s first true arch, a structure that changed everything about how buildings could be made. Before Balban’s tomb, Indian architecture relied on corbelled arches, where stones were stacked carefully on top of each other, each layer jutting out slightly until they met at the top. It was safe, predictable, and limited. The true arch that appeared here worked differently. It placed all faith in a single keystone at the centre, the piece that held everything together through pressure and balance rather than simple stacking. This was not just a construction technique.

This was a statement about confidence, about trusting principles that seemed to defy common sense. The arch here curves with mathematical precision, speaking a language borrowed from Central Asian and Persian builders who understood forces and weights in ways Indian artisans were beginning to explore. Some historians believe a dome once rose above these arches, which would make it India’s first true dome as well. That dome has vanished now, collapsed into dust and memory. But the arches survive, casting shadows that move across empty ground as the sun travels.

Somewhere beneath your feet, Balban’s actual grave should rest. Nobody knows exactly where. The tomb chamber shows no sign of it, no marker, no indication that the Sultan who terrorised enemies and rebuilt Delhi even lies here. Nearby stands another tomb, better preserved, decorated with Persian verses. That belongs to Khan Shahid, Balban’s son, who died fighting Mongol invaders. Visitors often confuse the two tombs, assuming the prettier one must belong to the Sultan. History plays these tricks, giving fame to the wrong places while the real revolutionaries wait in silence.

When Ruins Became Refuge: Mehrauli’s Secret Life

For centuries after Balban’s death, his tomb lived a second life that the Sultan could never have imagined. The grand Haven of Safety became an actual haven for people Delhi had cast aside. Debtors running from creditors found shelter in these vaulted chambers. Wanderers with nowhere else to go made homes against these ancient walls. The outcast, the forgotten, the desperate took refuge where a Sultan slept, creating an accidental poetry that Balban himself might have understood. After all, he knew what it meant to be powerless, to be owned by others, to claw your way up from nothing. Mehrauli grew around the tomb, becoming a neighborhood of layered histories, each century adding new stories to old stones.

The area has been transformed into an archaeological park in recent decades, where monuments from different eras stand close together like gossiping relatives. Conservation teams have started restoration work on Balban’s tomb, carefully stabilising walls that have survived against improbable odds. Experts call this structure a textbook example of early Indo-Islamic architecture, the moment when Indian building traditions began mixing with techniques from Central Asia and Persia. But treating it only as an educational example misses something important.

This tomb breathed with human desperation and hope for hundreds of years. Its walls heard prayers from people who had nothing left except these stones. The wild grass growing through cracks tells its own story about nature reclaiming what humans build. Birds nest in the high corners where the dome once curved. Every monsoon tests the old mortar, washing away a little more of the past. Yet enough remains to spark imagination, to make visitors wonder about the man who ordered these arches built, who chose simplicity over decoration, strength over beauty.

Tomb of Ghiyas-ud-din Balban: What Balban’s Silence Teaches Modern India

Standing in this roofless tomb today feels different from visiting the Taj Mahal or Humayun’s Tomb. There is no ticket counter, no guide reciting memorised facts, no crowd jostling for photographs. Instead, there is space for thinking, for connecting present concerns with medieval solutions. Balban’s legacy speaks to contemporary India in unexpected ways. His rise from slavery to sultanate reminds us that the past contains more social mobility than we sometimes imagine.

His architectural innovation shows that major changes often happen quietly, without fanfare or immediate recognition. His choice to build a plain tomb rather than a decorated monument suggests a different relationship with mortality and memory. He may have understood that true permanence comes from ideas rather than ornamentation.

The students who sketch these arches in their notebooks are learning more than architectural history. They are absorbing lessons about resilience, about how structures survive when they are built on sound principles rather than surface appeal. Conservation workers restoring the tomb understand they are not just preserving old stones but protecting a specific moment when Indian culture was being remade by contact with other traditions. History lovers who seek out this obscure monument instead of famous tourist sites are choosing complexity over simplicity, real stories over polished narratives. Mehrauli’s archaeological park has become a classroom without walls, teaching anyone willing to listen about Delhi’s origins, about the Sultanate period that shaped North India for centuries.

In this tomb’s bare honesty, in its refusal to pretend or decorate, there lives a challenge to our current moment. Modern India builds constantly, erecting shopping malls, apartment towers and metro stations. But how much of what we make today will matter in seven hundred years? What innovations are we pioneering that future generations will study? Balban’s tomb suggests that lasting impact comes not from size or decoration but from solving fundamental problems in new ways.

The true arch, the confident keystone, the structural logic that defies gravity through understanding rather than force, are these walls’ real inheritance? Stand here long enough and the present moment feels less urgent, less final. Empires rise and crumble, buildings decay, graves get lost, yet somehow the essential innovations survive, waiting in plain sight for anyone curious enough to look beyond the obvious.

Also Read: Students’ Sea Turtle Conservation Network: Chennai’s Midnight Warriors Saving Ancient Lives

You can connect with DNN24 on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel.