Red Fort stands as more than just sandstone and marble. Diwan-i-Aam and Diwan-i-Khas stand as the twin hearts of Red Fort, where Mughal emperors governed an empire and revolutionary leaders plotted India’s freedom. This fortress embodies the essence of India’s struggle for freedom and the grandeur of the Mughal Empire. Originally called Qila-e-Mubarak or Qila-e-Shahjahanabad, the structure earned its popular name from the red sandstone that forms its imposing walls. While Agra also has a Red Fort, Delhi’s version became the recognised symbol during India’s freedom movement. Subhas Chandra Bose rallied his Azad Hind Fauj with the cry “Chalo Dilli, Lal Qile par jhanda phehrayenge.” That slogan embedded the fortress permanently in public consciousness.

The name became so widespread by the 1930s and 1940s that “Lal Qila” now refers exclusively to Delhi’s monument. Within these walls, two particular spaces held extraordinary significance. The Diwan-i-Aam and Diwan-i-Khas served as the administrative backbone of the Mughal Empire. These halls witnessed crucial decisions that shaped subcontinental history for over two centuries. Built under Shah Jahan’s vision, these courts continued to function until Bahadur Shah Zafar’s final days in 1857. Today, visitors walk through spaces where emperors once dispensed justice, received ambassadors, and governed vast territories.

The Public Court: Diwan-i-Aam’s Democratic Vision

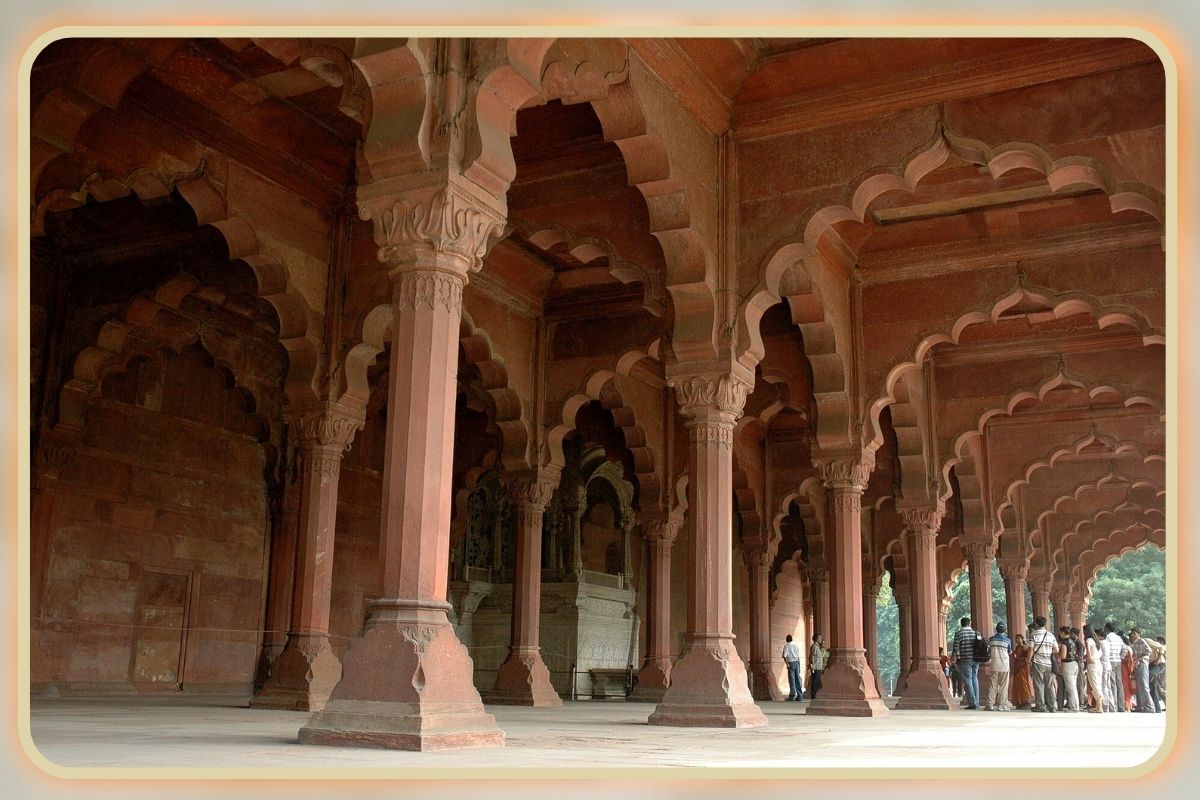

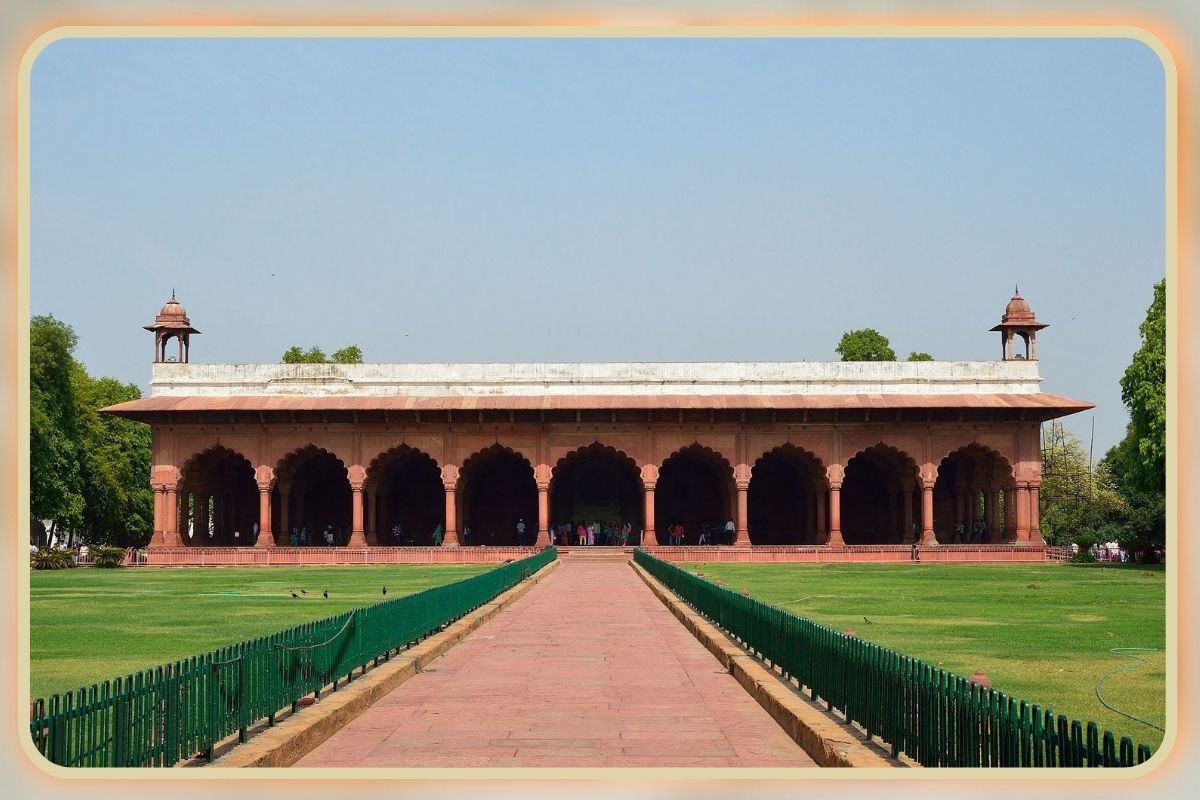

Diwan-i-Aam translates as the Hall of Public Audience, though the term “public” requires proper context. This magnificent structure served as the general court where Shah Jahan and his successors met military generals, ministers, and petitioners from across the empire. Construction was completed around 1648, after nearly nine years of intensive labour. The inaugural ceremony held exceptional grandeur. Shah Jahan entered through the Naubat Khana and proceeded directly to the Diwan-i-Aam, where his throne awaited. His son Dara Shikoh showered him with gold coins during this procession. A golden canopy decorated with pearls and precious stones sheltered the throne.

The entire setup demonstrated imperial wealth and power. This hall functioned as the Mughal equivalent of a parliament or executive secretariat. Army commanders sought orders here. Officials presented their reports. Citizens brought grievances requiring imperial attention. The space operated as the empire’s central nervous system, where information flowed inward and commands radiated outward. The tradition continued unbroken until 1857, when Bahadur Shah Zafar presided over meetings regarding the rebellion against British rule. General Bakht Khan and other revolutionary leaders gathered at this very spot to coordinate their resistance. Orders issued from the Diwan-i-Aam reached every corner of insurgent-controlled territory.

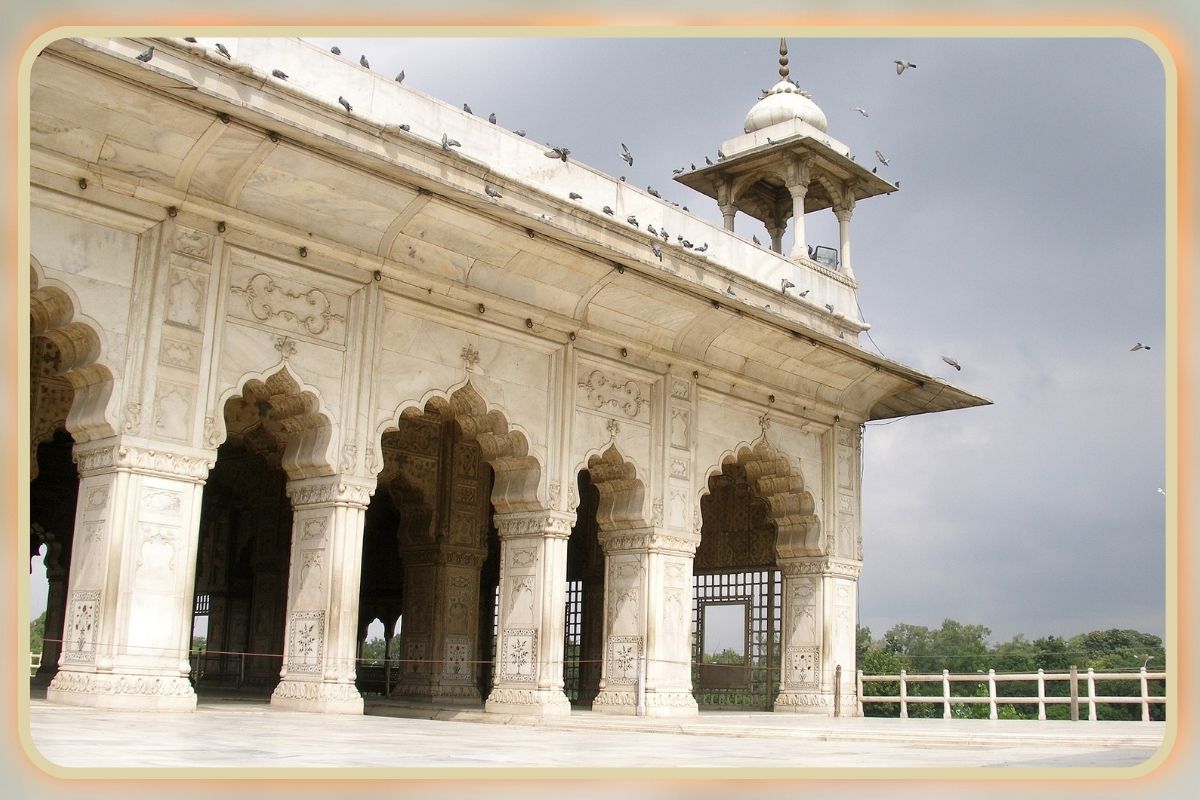

Architecture Tells Stories of Glory and Loss

The Diwan-i-Aam’s present appearance differs substantially from its original splendour. Behind the main hall, a white marble structure marks where emperors sat enthroned. The famous Peacock Throne once occupied this space. Crafted from solid gold and encrusted with diamonds and jewels, it ranked among the world’s most valuable objects. Nader Shah’s invasion in 1739 resulted in the theft of numerous treasures, including those of countless others. Successive raids stripped the hall of embedded jewels, gold leaf work, and ornamental decorations. The floor once featured precious stones set in intricate patterns.

The canopy overhead glittered with gold and pearls. Raiders and looters systematically stripped these riches over the course of decades. What remains now serves as a poignant reminder of its former magnificence. Yet the scale and proportion still convey the grandeur that once existed. The open pavilion design allowed air circulation while maintaining visibility. Shah Jahan could observe everyone present while remaining elevated above the crowd. Guards stationed at the Naubat Khana announced arrivals through musical signals that echoed through the complex. This acoustic system ensured smooth coordination of court proceedings. The white structure visible today underwent restoration, but it preserves the basic layout that facilitated Mughal governance for two centuries.

Rang Mahal: Where Culture Flourished

Adjacent to the administrative spaces stood Rang Mahal, the Palace of Colours. This section housed cultural activities and entertainment. Shah Jahan possessed not merely wealth but refined taste in spending it. He patronised arts, music, and literature while constructing architectural marvels. Rang Mahal exemplified this cultural sophistication. The palace hosted performances, artistic gatherings, and refined social interactions. Different accounts describe varying uses, partly because functions changed between Shah Jahan’s era and later periods. Each successive emperor modified spaces according to personal preferences and practical needs.

Much of the original decoration disappeared through neglect and deliberate destruction. However, the surviving structures reveal the importance placed on cultural refinement. The Mughals understood that civilisation required more than military strength. Art and culture provided the soft power that complemented administrative authority. Rang Mahal illustrates how the Red Fort served as a comprehensive ecosystem that supported governance, culture, and daily imperial life. The palace integrated seamlessly with other structures, creating a unified complex where different aspects of royal existence unfolded.

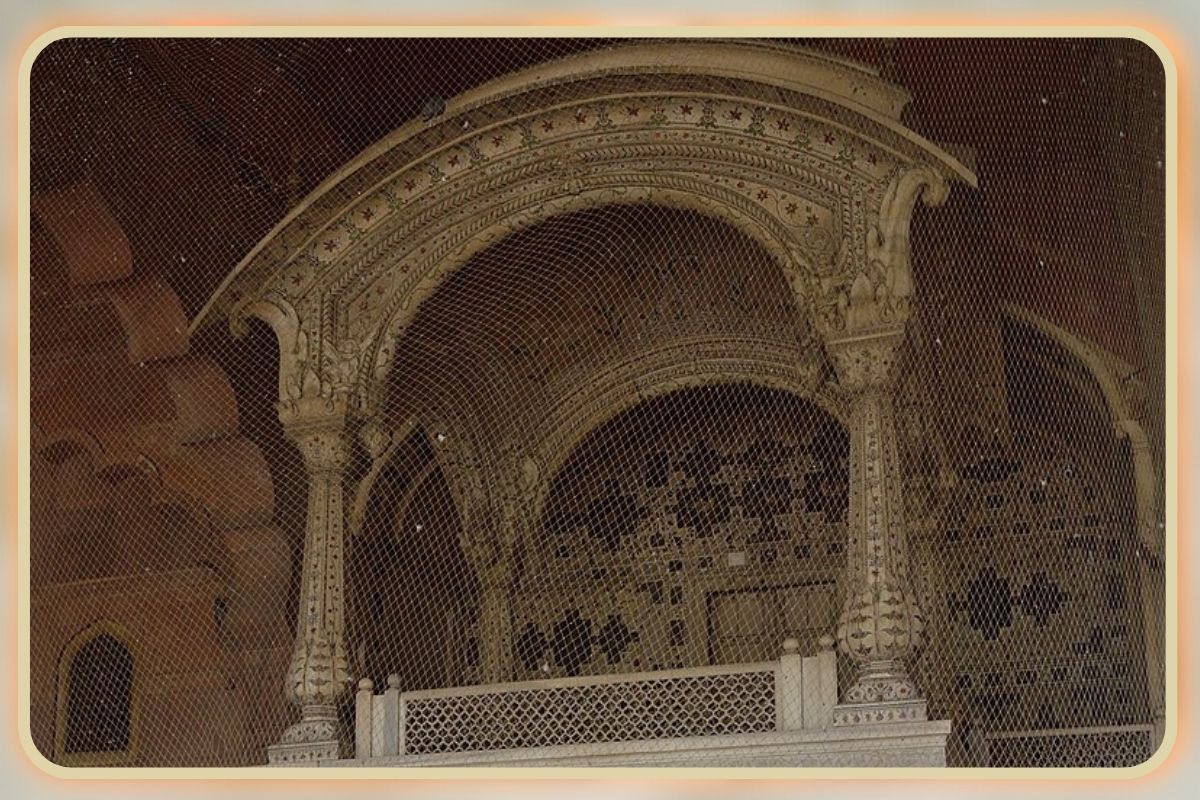

The Private Sanctuary: Diwan-i-Khas Unveiled

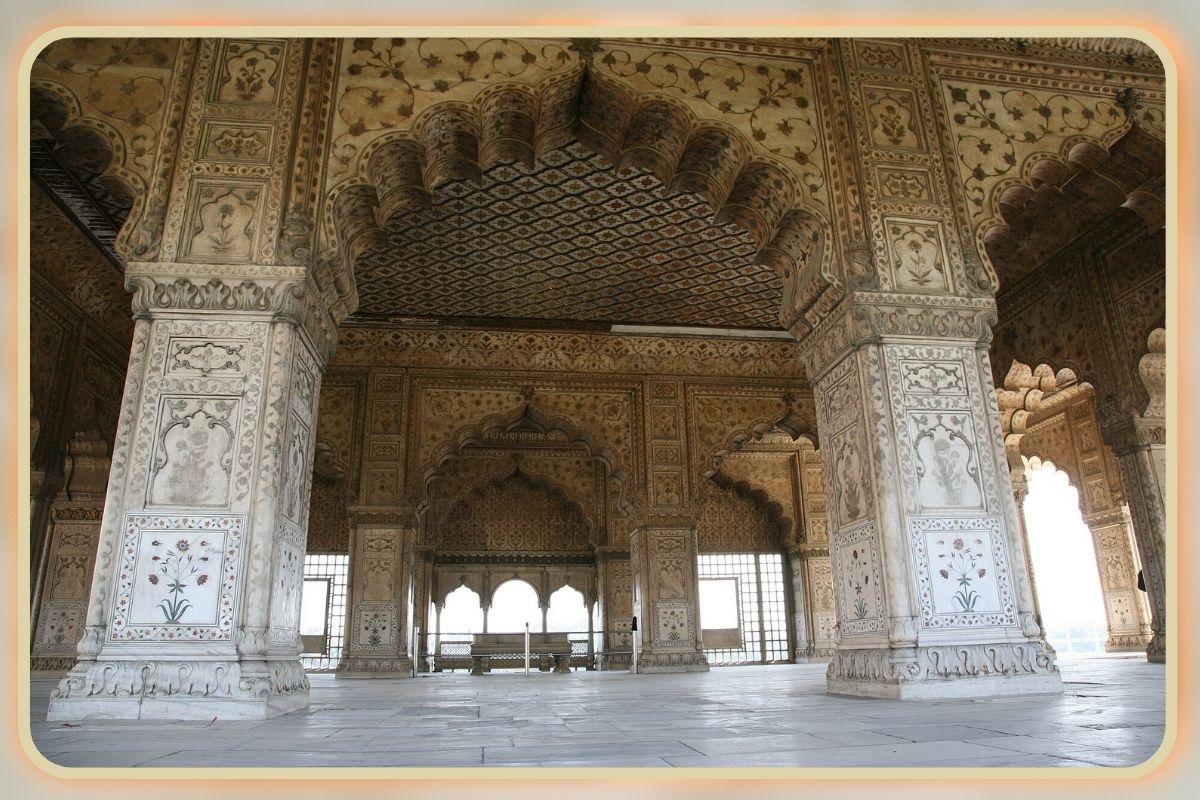

While Diwan-i-Aam handled general administration, Diwan-i-Khas served an entirely different purpose. This Hall of Private Audience hosted exclusive meetings reserved for select individuals and sensitive matters. The architectural distinction between the two halls reflects their functional separation. The Diwan-i-Khas is entirely constructed of white marble, Shah Jahan’s favoured material. The structure originally featured gold leaf engravings and embedded precious stones throughout its walls and pillars. These decorations disappeared gradually as various conquerors looted the fort. The British systematically stripped remaining valuables after 1857. Today’s structure presents bare elegance rather than jewelled magnificence.

Yet the marble craftsmanship itself remains impressive. Delicate carvings demonstrate the skill of artisans who worked under imperial patronage. The hall functioned as a combination of the Prime Minister’s office and the Royal Secretariat. Only trusted advisors, important diplomats, and close associates gained entry. Confidential discussions about military strategy, diplomatic relations, and sensitive state matters occurred within these walls. The intimate scale fostered frank conversation while maintaining a sense of ceremony. Shah Jahan designed this space to strike a balance between accessibility and exclusivity, creating an environment where serious governance could proceed without public scrutiny or unnecessary formality.

The Paradise Stream: Nahr-i-Behisht

A remarkable water system connected various sections of the Red Fort. The Nahr-i-Behisht, meaning Stream of Paradise, flowed through multiple buildings, including the Diwan-i-Khas. This network served practical and aesthetic purposes simultaneously. Fresh water circulated constantly, cooling the air in Delhi’s intense summer heat. Fountains positioned along the channel added visual beauty while enhancing the cooling effect. The system’s engineering proved remarkably sophisticated. Building orientations aligned to capture prevailing winds, which passed over water before entering inhabited spaces. This natural air conditioning provided relief long before modern technology existed. The fountain mechanisms operated through carefully calibrated water pressure rather than pumps or motors.

Unfortunately, later attempts to understand and replicate the system caused damage to its delicate components. The original designers possessed engineering knowledge that subsequent generations struggled to match. The name “Behisht” refers to paradise, suggesting the refreshing comfort this water system provided. Strolling beside flowing water while conducting state business must have offered a welcome respite from Delhi’s climate. The channels also carried symbolic meaning, representing abundance and prosperity flowing throughout the empire. Today, the channels remain dry, but their paths trace the thoughtful design that made the Red Fort habitable and pleasant despite challenging weather conditions.

A Symbol of Freedom’s Struggle

Red Fort’s significance extends far beyond Mughal history. The fortress became central to India’s independence movement, particularly after the 1857 uprising. That year’s rebellion, known as the First War of Independence by many historians, centred on Delhi, specifically at the Red Fort. Revolutionary leaders proclaimed Bahadur Shah Zafar as Emperor of India, attempting to restore legitimate governance after decades of British encroachment. The rebellion’s suppression brought horrific violence. British forces executed thousands at the fort, using cannons and public hangings to terrorise the population. They deliberately chose the Red Fort to demonstrate their power and humiliate the defeated.

Subsequently, the British held an elaborate durbar at the Red Fort, summoning Indian princes to acknowledge colonial supremacy. They aimed to replace Mughal legitimacy with their own authority. This historical context explains why Subhas Chandra Bose specifically targeted the Red Fort as a symbolic objective. Reclaiming the fortress meant reclaiming sovereignty. When independence finally arrived on August 15, 1947, Jawaharlal Nehru hoisted the national flag at the Red Fort.

This tradition continues annually, with the Prime Minister addressing the nation from the ramparts of the fort. The choice of location deliberately asserts that India’s legitimate rulers now govern from the same place where emperors and colonial masters once held power. The Red Fort thus transformed from a Mughal administrative centre to a colonial trophy to India’s most potent symbol of freedom.

Also Read: Dark History of Khooni Darwaza: Delhi’s Blood-Stained Gateway

You can connect with DNN24 on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel.