Delhi holds within its boundaries a place whose very name sends shivers down the spine. Khooni Darwaza, or the Blood Gate, stands today as a quiet witness to centuries of violence and tragedy. Most residents pass by this monument without a second glance, treating it like any ordinary landmark. Yet beneath its weathered stones lies a history soaked in bloodshed that few truly understand. This gateway, built during an era of empire and conquest, has witnessed some of the most horrific episodes in Indian history. From massacres to public executions, from the fall of dynasties to the struggle for independence, Khooni Darwaza has seen it all. The name itself tells a story, though not the complete one. What began as Kabuli Darwaza, a simple directional gateway, transformed into a symbol of terror and suffering through the violent events that unfolded at its threshold over the centuries.

The Original Identity: From Kabuli Darwaza to Lal Darwaza

Its current ominous name did not always include Khooni Darwaza. Historical records and the board displayed at the site still refer to it as Lal Darwaza, the Red Gate. Many historians believe its original name was Kabuli Darwaza, meaning the gateway leading toward Kabul. This naming convention followed a logical pattern used throughout Delhi, where gates indicated the direction of travel, similar to the Kashmiri Gate that pointed toward Kashmir. Sher Shah Suri, a great administrator and ruler who revolutionised road transport in medieval India, constructed this gateway as part of his extensive communication system.

His vision included the famous Grand Trunk Road, connecting distant parts of the subcontinent through an efficient network of routes and checkpoints. The gateway served a practical purpose in those times, functioning much like modern toll plazas, where travellers entering or leaving the city would be registered. Delhi had thirteen such gates, and this particular one marked the path leading northwest toward Afghanistan. The transformation from a simple directional marker to a monument associated with death and violence came gradually, earned through the terrible events that repeatedly chose this location as their stage.

Nadir Shah’s Massacre: The First Stain of Blood

The gateway’s association with bloodshed began in earnest during the eighteenth century when Nadir Shah, the Persian invader, descended upon Delhi with his armies. His attack on Hindustan marked one of the darkest chapters in the city’s history. After conquering Delhi, Nadir Shah’s soldiers unleashed a massacre so brutal and extensive that the term “Nadir Shahi” entered common vocabulary as a synonym for genocide and mass slaughter. Historical accounts suggest that Khooni Darwaza was the starting point of this carnage. The massacre began at this very spot before spreading like wildfire through the streets of Delhi, claiming countless Indian lives.

The scale of violence was unprecedented, and the memory of those days lingered long after Nadir Shah departed with his plunder. This event established the gateway’s reputation as a place of horror, though unfortunately, it would not be the last time blood would flow at its threshold. The massacre demonstrated the vulnerability of Delhi and its people during periods of weak central authority, and the gateway became forever associated with that moment when the city fell prey to foreign brutality and unchecked violence.

The Tragedy of 1857: Where Princes Were Executed

The most significant and heartbreaking episode in the history of Khooni Darwaza occurred on 22 September 1857, during the aftermath of India’s First War of Independence. Three Mughal princes, sons of the last emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar, were brought to this spot by Major Hudson of the British forces. These young men had served as commanders in the rebellion against British rule, fighting for their country’s freedom and their family’s honour. Hudson captured them after they had been promised safe passage, but betrayal awaited them instead. At point-blank range, after being stripped of their clothes and dignity, the princes were shot dead at this gateway.

Their bodies were then taken to Chandni Chowk, where they hung for days as a warning to anyone who dared resist British authority. The poet Mirza Ghalib, who lived through these terrible times, captured the anguish of that period in his verses, lamenting that these royal princes received neither proper burial nor a marked grave, their bodies treated with contempt rather than the respect their station deserved. Hudson himself boasted about the execution, claiming proudly that he had killed the leaders of the rebellion with his own hands and felt no remorse for what he called necessary justice.

The Aftermath: Delhi’s Streets Run Red

The execution of the three Mughal princes on 22 September 1857 marked not an ending but a beginning. What followed was a systematic massacre that spread throughout Delhi, starting from Khooni Darwaza and reaching every corner of the old city. British soldiers, given free rein to exact revenge for the rebellion, hunted down residents street by street, showing no mercy to anyone suspected of supporting the freedom fighters. Historical accounts describe how even Chandni Chowk’s famous thoroughfare became a killing ground, with soldiers searching houses and dragging out inhabitants for summary execution.

The scale of this retribution exceeded even the horrors of Nadir Shah’s earlier massacre. Ghalib wrote to a friend during those dark days, saying simply that he was alive and grateful for it, but warning against discussing anything further for fear of attracting deadly attention. For several months before 22 September, British control over Delhi had actually lapsed, making the recapture of the city and the brutal punishment that followed even more significant in colonial calculations. The massacre served as a deliberate demonstration of power, meant to crush any remaining spirit of resistance and establish British supremacy beyond question.

Partition Violence and Later Bloodshed

The gateway’s connection to violence did not end with the events of 1857. When India gained independence in 1947, the terrible communal riots that accompanied Partition also touched this cursed spot. Refugees attempting to flee the violence found themselves trapped and killed near Khooni Darwaza, adding yet another layer to its tragic history. The location’s association with death extended beyond the gateway itself to the surrounding area. Adjacent to Khooni Darwaza stands Maulana Azad Medical College, a respected institution today but formerly a British prison where numerous freedom fighters were hanged.

A stone plaque at the site lists the names of revolutionaries executed there, including members of the Ghadr Party who were sentenced to death in 1915 for their role in attempting to overthrow colonial rule. The entire neighbourhood thus became a landscape of martyrdom and suffering, with blood spilt across generations for different causes but united by the common thread of resistance against oppression. Stories persist among locals about supernatural occurrences at the gateway, with some claiming to have seen apparitions of Zeenat Mahal, the mother of the executed princes, or experienced unexplained phenomena that supposedly affect British visitors in particular.

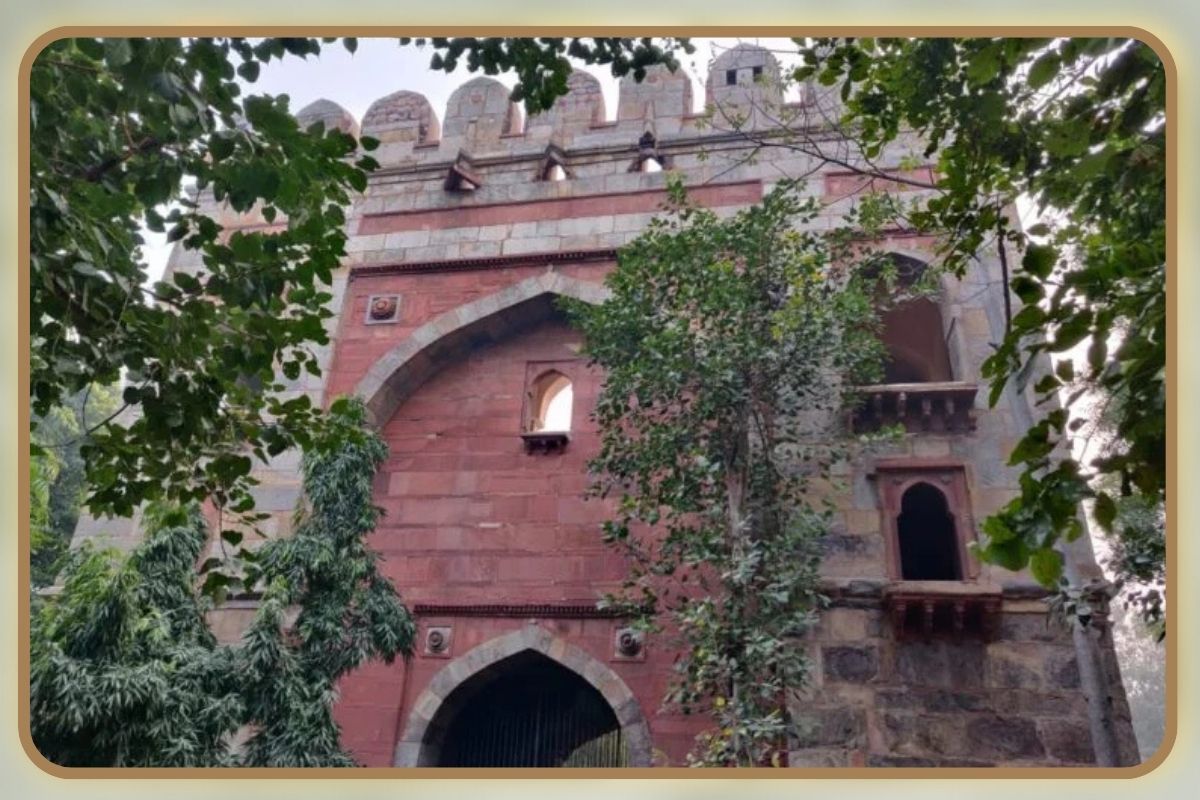

A Forgotten Monument: Why History Fades

Despite its profound historical significance, Khooni Darwaza remains largely neglected and forgotten by both authorities and the general public. The gateway is situated in a prime location near a central medical college, with thousands of people passing by daily without understanding what transpired there. The contrast between the monument’s importance and its current obscurity raises troubling questions about how we choose to remember our past. As a site where leaders of the 1857 uprising were executed without trial, where massacres began that devastated entire populations, Khooni Darwaza deserves recognition as a memorial to India’s freedom struggle.

Yet no substantial commemorative structure marks its significance beyond the original Mughal-era gateway and a small plaque mentioning the princes’ execution. Annual remembrance events remain rare or nonexistent, and educational initiatives to inform the public about the site’s history appear to be minimal. The failure to properly honour this location represents a broader problem in historical preservation and memory. When landmarks connected to defining moments in national history fade into obscurity, we risk losing touch with the struggles and sacrifices that shaped our present. The story of Khooni Darwaza deserves better than quiet neglect in the shadow of busy roads and modern institutions.

Also Read: Isa Khan’s Tomb: A Timeless Gem of Delhi’s Mughal-Era Heritage

You can connect with DNN24 on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel.