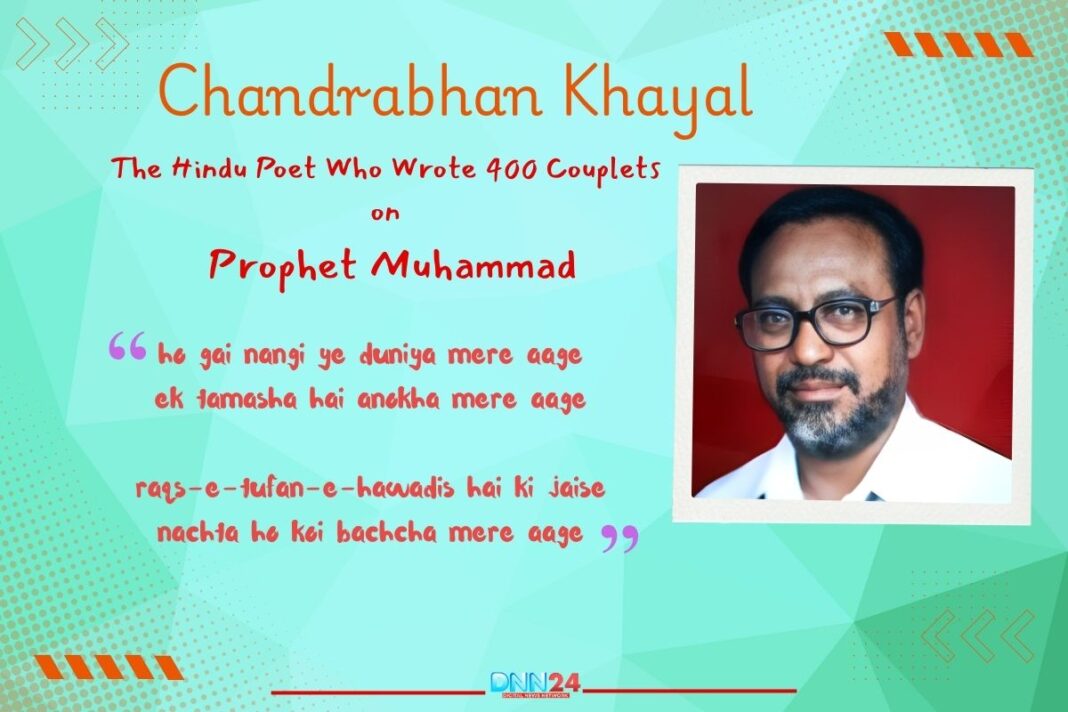

A dusty village lane in Madhya Pradesh. A ten-year-old boy crouching over borrowed Urdu books, teaching himself a script his school never offered. No teacher stood beside him. No madrasa welcomed him. Just raw determination and a heart that refused to accept the boundaries others built between languages and faiths. This boy, Chandrabhan Khayal, would grow up to shake the very foundations of what India believed about religious and linguistic borders.

sirf ek hadd-e-nazar ko aasman samjha tha main

Chandrabhan Khayal

aasmanon ki haqiqat ko kahan samjha tha main

Born in April 1946 in Babai village of Hoshangabad district, Chandrabhan came from modest means. His family worked the land and ran small trades, nothing extraordinary by village standards. But something burned inside this child that nobody quite understood. While other boys played in the fields, he haunted the local library, memorising Ghalib and Mir Taqi Mir by lamplight.

ho na ho aas-pas hai koi

Chandrabhan Khayal

mere jitna udas hai koi

After graduating from Sagar University, he did what countless dreamers before him had done. He left for Delhi, taking a job at a petrol pump while his real life unfolded in poetry gatherings across the city. The legendary Firaq Gorakhpuri spotted something special in this young man and gave him a new identity: Khayal, meaning a fleeting thought. Under the guidance of Pandit Ramkrishna Muztar Kakodwi, that fleeting thought became an eternal flame.

From Village Dust to Literary Legend

Babai village offered little to a boy hungry for words that lived beyond the visible world. The nearest library became young Chandrabhan’s second home, though it stocked mostly Hindi texts. Urdu poetry called to him like a secret language of the heart, and he answered by teaching himself from whatever fragments he could find. At a railway bookstall during a family wedding trip to Bhopal, he bought a Hindi-Urdu primer for fifty paise. Three months later, locals stood amazed at his fluency in a script and language he had never formally studied.

chilchilati dhup sar par aur tanha aadmi

Chandrabhan Khayal

aah ye KHamosh patthar aur tanha aadmi

His parents could not quite grasp this obsession. Farming needed hands, not dreamers. But Chandrabhan proved that dreaming and working were not opposites. He completed his studies while devouring poetry collections, writing his early verses under the pen name Chandra. Village gatherings gave him his first taste of applause, but his ambitions stretched far beyond those dusty courtyards.

justuju ke panw ab aaram sa pane lage

Chandrabhan Khayal

ab hamare pas bhi kuchh raste aane lage

Delhi in the 1960s and 70s buzzed with Urdu culture, despite the wounds of partition still being fresh. Chandrabhan worked at a petrol pump during the day, his hands smelling of grease and fuel. Nights belonged to mushairas, those poetry gatherings where words carried more weight than gold. He attended every session he could afford, often going hungry to save money for entry.

phir lauT ke aaya hun tanhai ke jangal mein

Chandrabhan Khayal

ek shahar-e-tasawwur hai ehsas ke har-pal mein

The legendary Firaq Gorakhpuri heard this young man’s verses at one such gathering. Something about the raw honesty and the unique perspective of a Hindu voice in Urdu poetry struck Firaq deeply. He renamed the young poet Khayal, transforming an identity and setting a destiny in motion. Under Pandit Ramkrishna Muztar Kakodwi’s mentorship, Khayal’s verses gained polish without losing their fierce originality.

Building Bridges Through Words

Journalism opened new doors for Khayal. He joined Urdu dailies like Savera and Qaumi Aawaz, learning to sharpen his thoughts into headlines while keeping his poetry alive in the evening hours. Rising to become chief editor of Bhavya Bharat Times gave him a platform to promote the very thing he embodied: unity across false borders.

zindagani ranj aur gham ke siwa kuchh bhi nahin

Chandrabhan Khayal

uf ki har-dam sog-o-matam ke siwa kuchh bhi nahin

His first major collection, Sholon ka Shajar, appeared in 1979 and set Urdu literary circles ablaze. Here was a voice that refused easy categories, a Hindu poet writing with the depth and devotion usually associated with Muslim masters of the form. Critics struggled to place him. Readers loved him. International recognition arrived when Iran invited him to symposiums, where his recitations left audiences of 150 poets stunned.

daulat-e-haq mujh ko hasil ho gai hai

Chandrabhan Khayal

zindagi ab aur mushkil ho gai hai

His masterwork, Laulak, published in 2002, changed everything. Thirteen years in the making, this epic nazm of 400 couplets spanning 100 pages told the life story of Prophet Muhammad. No poet had attempted something of this scale and devotion in nazm form. The title itself carried weight: Laulak, meaning “if you were not there,” expressing the divine significance of the Prophet’s existence. The book earned him invitations to Mashhad in 2004, where his recitations moved audiences to tears.

sard sannaTon ki sab sargoshiyan le jaunga

Chandrabhan Khayal

main jahan bhi jaunga dil ki zaban le jaunga

Awards followed in waves. The Uttar Pradesh Urdu Academy honoured him. Delhi Urdu Academy recognised his contribution. Madhya Pradesh bestowed the title of Sheri Bhopali. The prestigious Makhanlal Chaturvedi Samman acknowledged his role in building cultural bridges. Yet his most powerful recognition came from ordinary readers across faiths who found in his words a reflection of the India they wanted to live in.

The Couplet That Defines Our Times

Among Khayal’s vast body of work, one couplet cuts through the noise of contemporary India with surgical precision: “Inhen mandir banana hai, unhen masjid banana hai / Koi sunta naheen unki, jinhen ik ghar banana hai.” Some want to build temples, others want to build mosques. Nobody listens to those who want to build a home. Written decades ago, these lines could have been composed yesterday.

kabhi jo shab ki siyahi se na-gahan guzre

Chandrabhan Khayal

hum ahl-e-zarf har ek soch par garan guzre

Khayal’s other works carry similar weight. Sulagti Soch ke Saye, written in Hindi, addresses the burning shadows of divisive thoughts. Subh-e-Mashriq ki Azan calls out like a dawn prayer for a divided land. Gumshuda Aadmi ka Intezar speaks of waiting for lost souls, a theme that resonates painfully with today’s migrant crises. Kumar Pashi: a selection of his finest poems and his complete works, published by the National Council for Promotion of Urdu Language in 2012, stand as testaments to a life lived in service of words that heal.

KHol ke andar simaT kar rah gaya main

Chandrabhan Khayal

apne sae se bhi kaT kar rah gaya main

His position as vice chairman of the National Council for Promotion of Urdu Language was not just an administrative role. Khayal used it to actively promote Urdu as a language belonging to all Indians, not just Muslims. He appeared regularly on television and radio, bringing poetry to audiences who might never attend a traditional mushaira. In an era when Urdu is often falsely branded as a “Muslim language,” Khayal’s entire life stands as a correction to that dangerous misconception.

Why Khayal Matters More Than Ever

The India of 2025 needs Chandrabhan Khayal’s voice more desperately than the India of his youth ever did. Social media amplifies divisions at lightning speed. Politicians exploit religious fault lines for electoral gains. Communities that lived together for centuries suddenly view each other with suspicion. Into this poisoned atmosphere, Khayal’s life and work arrive like a blast of clean air.

khol simaT ke andar simaT kar rah gaya main

Chandrabhan Khayal

apni sae se bhi kaT kar rah gaya main

His story carries a message that no manifesto or political speech can match. A boy from a Hindu family in a small village in Madhya Pradesh taught himself Urdu because he loved it. He became one of the language’s greatest modern poets. He wrote devotional poetry about the Prophet Muhammad that earned praise from scholars in Iran. He spent his career building bridges while others profited from burning them.

milta nahin KHud apne qadam ka nishan mujhe

Chandrabhan Khayal

kin marhalon mein chhoD gaya karwan mujhe

For today’s young people, especially content creators and writers, Khayal offers a roadmap through confused times. You do not need elite education to achieve greatness. A railway bookstall, a primer, and fierce determination can open worlds. You do not need to reject one identity to embrace another. Khayal remained proudly Hindu while becoming an Urdu master. His journey from petrol pump worker to nationally celebrated poet proves that circumstances of birth do not dictate circumstances of life.

ghaDi-bhar KHalwaton ko aanch de kar bujh gaya suraj

Chandrabhan Khayal

kisi ke dard ki lai par kahan tak nachta suraj

The fact that his most powerful couplets addressing religious division were written decades ago and still cut to the heart of current debates shows that some wisdom is timeless. Poetry, when written with truth and skill, does not age. It waits patiently for the moment when the world finally catches up to what the poet already knew.

aa raha hai shabab aane do

Chandrabhan Khayal

ab to ye inqalab aane do

Chandrabhan Khayal passed away, leaving behind a legacy that India will spend generations fully understanding. In archives and libraries, his books wait for readers ready to see that unity is not weakness but strength, that crossing borders enriches rather than diminishes, that a Hindu writing Urdu poetry about the Prophet is not a contradiction but a beautiful example of what India at its best has always been. The tomb of Chandrabhan Khayal is not made of stone. It is built from verses that refuse to let hate have the final word, from a life that insisted on seeing the human before the label, from a dream that one home for all matters more than a hundred separate shrines.

Also Read: Aazam Khursheed : The Poet Who Made Faces Speak & Still Matters

You can connect with DNN24 on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel.