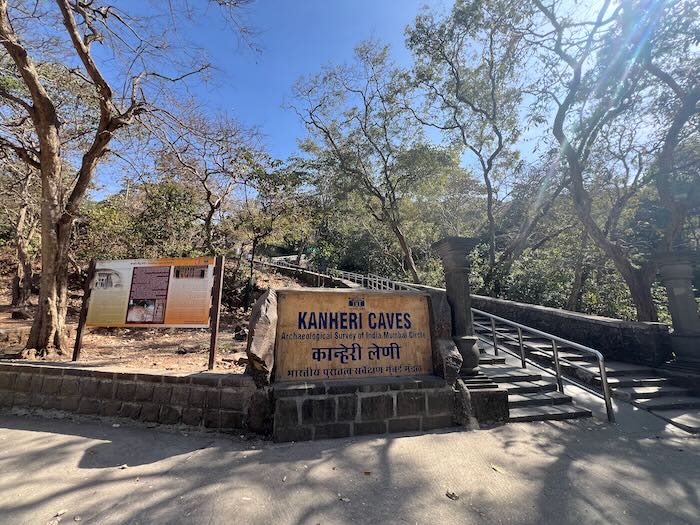

What if Mumbai’s wildest secret was not a hidden bar or rooftop restaurant, but a 2,000-year-old university carved into black mountains? Kanheri Caves sit quietly in Sanjay Gandhi National Park, holding stories that predate the city itself. These 109 rock-cut caves were once home to hundreds of Buddhist monks who turned bare basalt into a booming centre of learning and meditation. While modern Mumbai races forward with its trains and towers, Kanheri remains frozen in time, waiting for those curious enough to climb its ancient stone steps. This is not just another tourist spot gathering dust in guidebooks. This is where history breathes.

Kanheri Caves:When Merchants Carved Mountains Into Monasteries

The story begins around the 1st century BCE when Buddhist monks first looked at the dark basalt slopes of Krishnagiri and saw a possibility. These were not kings with grand armies funding massive projects. Instead, traders from nearby ports like Sopara and merchants from Kalyan pooled their resources to carve out simple meditation halls. They needed shelter during the brutal monsoon months, and the hard black rock provided exactly that.

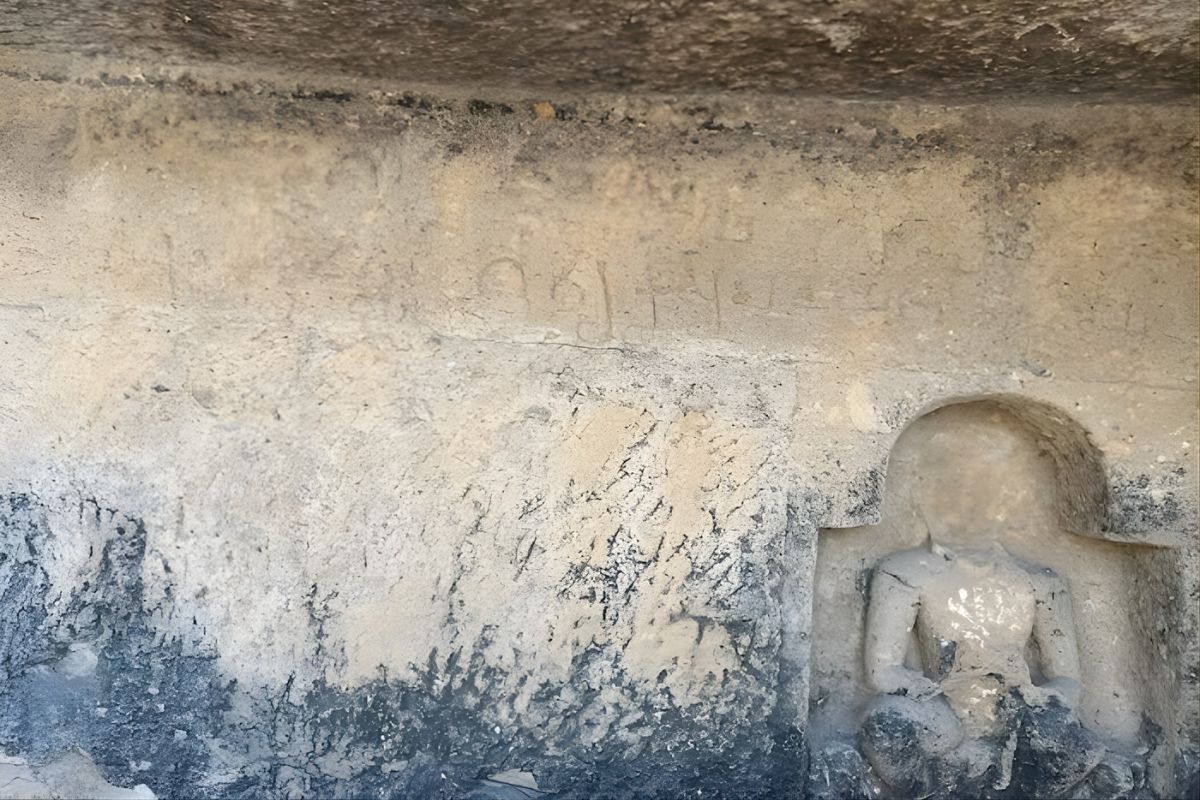

By 160 CE, during the Satavahana period, Kanheri had grown into something remarkable. The queen from the Rudradaman dynasty gifted water cisterns through her minister Sateraka, as recorded in Cave 5. Around 170 CE, ruler Yajna Sri Satakarni left his mark on the Great Chaitya in Cave 3. These inscriptions tell us that Kanheri was more than a religious retreat. It connected major trade routes with spiritual journeys, creating a unique space where commerce met contemplation.

The early caves followed Hinayana Buddhism, favouring simplicity. Plain stone cells, hard beds, and stupas without elaborate decorations defined this period. Then came the Mahayana wave after the 3rd century CE, bringing massive Buddha statues and compassionate Bodhisattvas. The Traikutaka dynasty continued to support the caves, with records from 494 CE attesting to their patronage. By the 10th century, 109 caves spread across the hillside, housing monks, students, and wandering scholars. Even Atisha, who later became famous in Tibet, studied meditation techniques here before his journey north.

Kanheri Caves: Architecture That Speaks Without Words

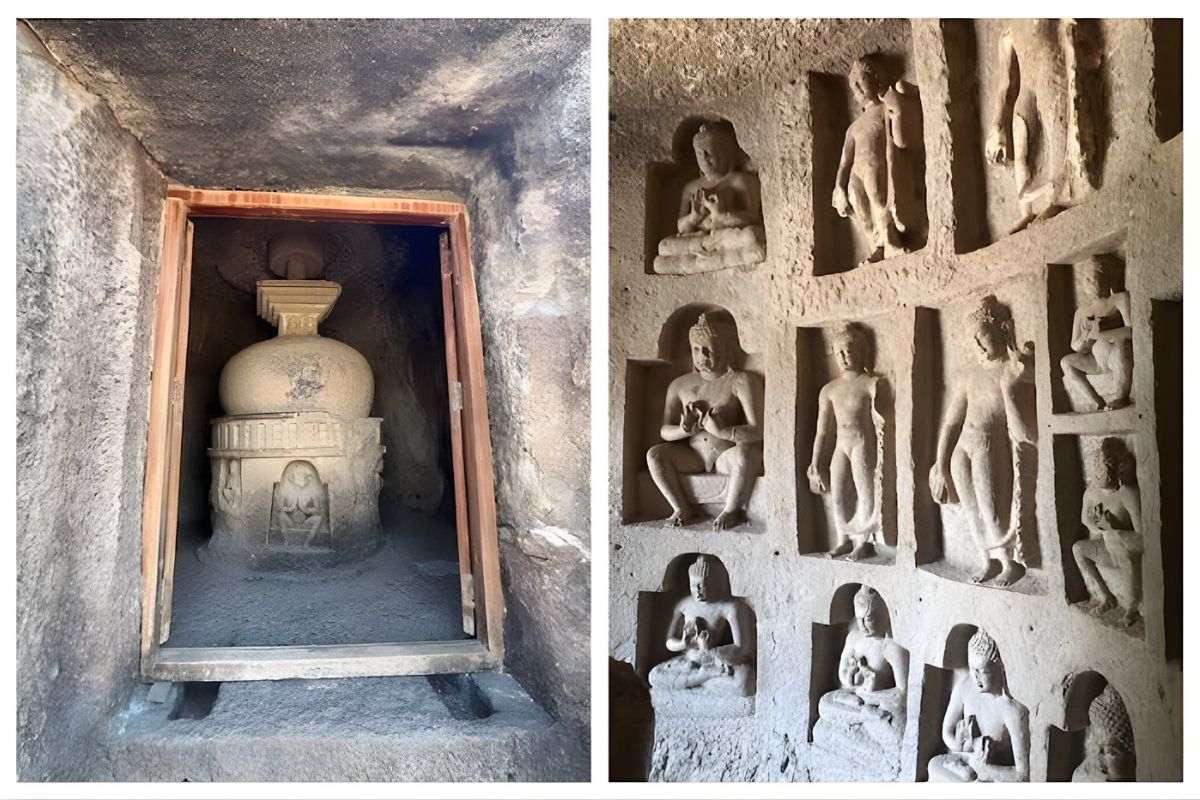

Walking into Cave 3 today feels like stepping into a different world. The Great Chaitya hall, inspired by the famous Karla Caves but with its own character, stretches before you with 34 pillars supporting a vaulted roof. At the centre stands a simple stupa, and at the entrance, two towering 23-foot Buddha statues keep watch as they have for centuries. Their robes, carved in the Satavahana style, flow with such detail that you can almost feel the fabric.

The viharas, or living quarters, scatter across the hillside like a stone village. Simple cells with raised stone beds once housed over 500 monks. Cave 11, known as Darbar Cave, served as the assembly hall where monks gathered to debate Buddhist philosophy and discuss community matters. The design mimics descriptions of Buddha’s first council, with a shrine at one end and stone benches arranged for group discussions. Cave 90 contains inscriptions in Pahlavi script, evidence that Persian traders also visited and contributed to this mountain monastery

Water management here was brilliant. Ancient engineers designed channels that caught monsoon rain from the hilltops and directed it into storage cisterns. The system in Cave 5 still works after 2,000 years, providing water to modern trekkers. While paintings have faded in most caves, the stone reliefs remain sharp. Jataka tales showing Buddha’s previous lives as various animals cover the walls. Multi-headed Padmapani carvings protected entrances from evil spirits. Smaller stupas in Caves 2 and 4 held clay seals with Buddha images, which were discovered alongside Bahmani-period coins during excavations.

Kanheri Caves: Daily Life in a Mountain Monastery

Dawn at ancient Kanheri meant the sound of chanting echoing through stone halls. Monks woke early, collected their simple porridge from donations given by visiting merchants, and began their daily routine. This was never an isolated monastery cut off from the world. Kanheri sat at the crossroads of major trade routes, with the port of Sopara just a day’s journey away. Merchants travelling with silk, spices, and precious stones stopped here, donating money and materials to gain spiritual merit.

The morning hours were spent in the chaitya halls, chanting sutras and meditating. Afternoons meant copying Buddhist texts, teaching younger monks, or carving new caves and decorations. Evenings brought community gatherings under large trees where monks debated philosophy and shared teachings. The water system that brought life to this rocky hillside required constant maintenance, with monks working together to keep channels clear and cisterns clean.

The peak period occurred between the 3rd and 6th centuries CE, when Kanheri served as a hub for scholars from Ujjain in central India and coastal trading communities. Over 100 caves were occupied, creating an authentic university atmosphere. Women also played important roles, with several inscriptions recording donations by queens who facilitated political marriages between the Satavahana and Saka kingdoms.

Archaeological excavations led by James Bird in the 1830s uncovered urns containing ashes mixed with precious items such as rubies, pearls, and gold cloth, evidence of elaborate Buddhist funeral practices. As centuries passed, changes came slowly. Hinduism gained followers, trade routes shifted, and by the 10th century, fewer monks remained. Eventually, the jungle reclaimed the caves, and Kanheri faded from active use, though never completely forgotten.

Kanheri Caves: Rediscovery and Modern Challenges

Portuguese explorers noted the caves briefly in the 16th century, but serious study began only when the British arrived. James Bird’s 1839 excavations opened sealed stupas, finding copper plates with Buddhist verses and precious stones. Later digs in 1853 by Ed West uncovered more seals and medieval coins, proving that people continued visiting Kanheri long after the monks left.

Today, Kanheri sits within the 103-square-kilometre Sanjay Gandhi National Park, officially protected by the Archaeological Survey of India. In 2025, the Bombay High Court mandated an expert panel comprising BMC officials and INTACH conservation specialists to better protect Kanheri and other nearby cave sites. Urban expansion threatens the park boundaries, yet visitor numbers keep growing. Recent archaeological surveys found seven pre-Kanheri rock shelters dating to the 1st century BCE, complete with ancient tools, proving this hillside attracted human settlement even before Buddhism arrived

Why Kanheri Matters Now

Kanheri offers something rare in Mumbai, a city of over 20 million people racing through crowded trains and endless traffic. Here, ancient water harvesting techniques inspire modern rainwater conservation projects. Buddhist groups hold meditation retreats, while weekend trekkers seek peace among the Jambulmal trees. Mini-trains ferry larger groups, but walking the 6-kilometre trail network reveals hidden corners and sudden views.

The winter months from November to February offer the best visiting conditions, with temperatures between 15 and 25 degrees Celsius and lush greenery from recent monsoons. Standing in Cave 3, touching pillars carved during the reign of the Satavahana kings, connects visitors directly to centuries past. Kanheri proves that Mumbai contains layers far deeper than its modern surface suggests, waiting for those willing to climb the stone steps and listen to what the ancient caves still have to say.

Also Read: Eklakhi Mausoleum: Pandua’s One Lakh Rupee Royal Secret

You can connect with DNN24 on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel.