Nobody puts Vijaygarh Fort on their travel list the first time. You hear of it sideways, through an old travel note, a line in a regional novel, or a fellow traveller who stood before its broken gateways and felt something unexplained. You do not reach it by wide highways and painted signboards. You approach through a landscape where the road narrows, trees press closer, and the noise of the present thins out. The fort does not announce itself like a polished monument. It appears almost reluctant, its ramparts half-swallowed by creepers, its stones worn loose by weather, yet its bearing firm, as though it has not quite finished deciding whether to accept its own ruin.

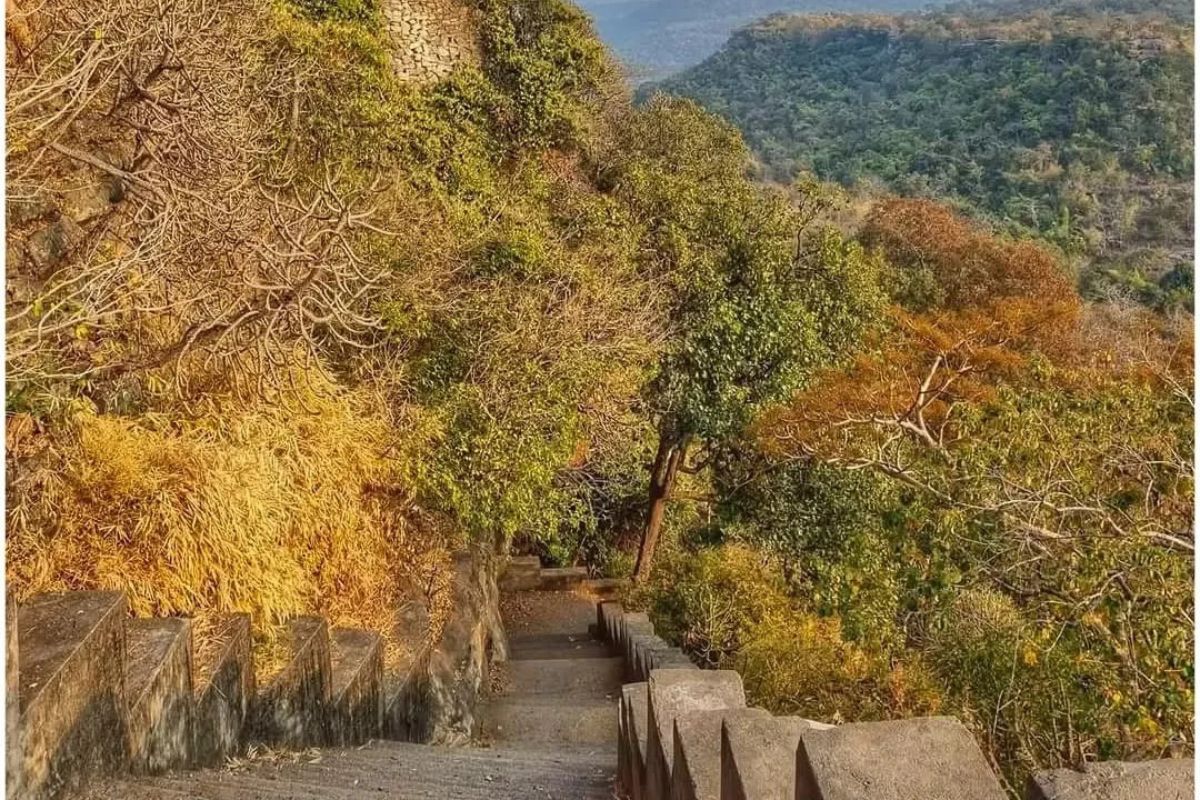

Vijaygarh Fort stands in Mau Kalan village of Chatra block in Sonbhadra district, Uttar Pradesh, about thirty kilometres southeast of Robertsganj. It rises near Dhandhraul Dam on the Robertsganj to Churk road, set against the stern hills of the Kaimur Range. The fort is nearly one hundred and five kilometres from Varanasi and can be reached by road, followed in parts by a short trek.

Its builders did not choose the ground by accident. The surrounding hills formed a natural line of defence. Thick forests offered both concealment and strategic advantage against advancing forces. Reservoirs close to the fort walls ensured a steady water supply for soldiers during sieges and for travellers and pilgrims in the harsh summer months. Today, its fractured courtyards still hold the quiet tension of royal ambition, military foresight, and the measured observations of colonial chroniclers, all layered within the same fading stone.

Foundations Built on Legend and Stone

Every old fort carries a founding story, and Vijaygarh holds one close to its roots. Local tradition connects this hill to a ruler from the age of the great epic wars, tying the fort to sacred imagination long before any dated inscription appeared on its walls. Whether that tradition is history or belief is a question that scholars debate quietly; the hill itself keeps its answer to itself.

What the ground record does suggest is that early medieval chiefs and tribal lineages settled this height and shaped it into a watchful post over routes, rivers, and the movement of grain, goods, and armies. Stones that lie scattered today have borne many languages and many names over what is believed to be roughly 14 or 15 centuries of habitation and use.

The name itself originated with a Rajput ruler, Vijay Pal, who is credited with rebuilding or substantially renovating the structure around the eleventh century. He called it the fort of victory. Standing among its present ruins, that word sounds almost contrary to what one sees. But it was never a description of a finished state. It was a declaration of intent, a bold announcement that this rock and height were meant to be a lasting statement of power rather than a temporary shelter.

Design as Strategy: Walls, Water, and Winding Paths

The fort’s builders did not think in straight lines. Pathways twist and double back rather than climb directly, forcing anyone approaching under hostile conditions to slow down, spread out, and expose themselves. Gateways were positioned to deny attackers clear sight lines. Inner areas remained hidden from direct view until the moment of approach. The thickness of the walls speaks not of decoration but of people who had learned, perhaps through earlier defeat, that survival depends as much on concealment as on force.

Water was treated as seriously as stone. Ponds like Ram Sagar near the fort stored reserves for daily use and for periods when the gates remained shut against external threats. Every drop was part of the plan. This kind of foresight was not common to every fort of the period. It marks Vijaygarh as a structure designed by minds that thought in terms of time, not only of battle.

As regional kings connected with the old city on the sacred river extended their influence, the fort shifted from a purely military structure into a node within a broader network of estates and outposts. Even as Mughal authority spread across the map, the fort adapted. It housed representatives, served as a managed post, and bent just enough to remain useful without losing the core weight of its stone identity.

Wars Fought in Low Tones

Vijaygarh’s battles are not the kind that fill the pages of standard history books. They breathe in lower registers: skirmishes on forested slopes, quiet resistance, alliances made and unmade across generations, during the centuries when northern and central territories saw repeated clashes between regional powers and incoming forces from the northwest. Holding a fort at this height meant controlling routes that carried both armies and provisions. Local tradition links Vijaygarh to the wider disturbances involving Turkic and Afghan campaigns, though detailed records of those confrontations are thin.

Later, figures from the Kashi line, among them Maharaja Balwant Singh and Chet Singh, appear in the fort’s recorded history. These were decades when the conflict was not simply between the king and outside force but between hereditary authority and a colonial company that used revenue demands, diplomatic pressure, and military threat as coordinated tools. When Chet Singh’s resistance against that company collapsed, the redistribution of estates directly affected Vijaygarh. Authority is divided between old landowning families and new political masters. The fort did not fall in a single remembered siege. It slowly leaked power across generations until silence replaced the last order issued from its walls.

Chandrakanta and the Fort of Fiction

If its military history whispers, its fictional life speaks at full volume. A nineteenth-century Hindi novelist placed Vijaygarh at the centre of a romance-adventure story full of tilisms, hidden passages, brave warriors, and a princess whose name, Chandrakanta, stayed in the popular imagination long after the book left the press. That novel gave the fort an emotional reality that no campaign map could provide. Readers who had never seen its walls began to picture them as the backdrop to loyalty, betrayal, and love.

The effect continues. Local guides point at certain corners and speak of underground tunnels and enchanted spaces drawn from the novel rather than from surveyed ground. Tourism planners in the region propose a Chandrakanta circuit with Vijaygarh as its anchor, inviting visitors to walk through the physical setting of a story that once kept an entire generation reading past midnight. Archive and imagination have become difficult to separate here, and that combination has given the fort a second kind of fame, one built not on conquest but on the staying power of a good story.

Present Condition: Pilgrims, Plans, and Open Questions

Today, Vijaygarh occupies several roles at once. It is a decaying military structure where vegetation has taken back what soldiers once held with considerable effort. It is a spiritual stop, particularly during the month of Shravan, when pilgrims collect water from its ponds and begin their journey to Shiva shrines, folding the fort quietly into a devotional route that has nothing to do with its military past. And it is a subject of tourism plans that speak of improved roads, better signage, and basic visitor facilities.

Conservation here is complicated by forest regulations and ecological sensitivity, which limit construction even as visitor numbers grow. That tension, between protecting the stones and maintaining the surrounding tree cover, defines the immediate challenge. The fort’s walls cannot simply be shored up with cement and called restored. The context that gives them meaning, the forest, the water bodies, and the old pathways, must stay intact alongside them.

Why Vijaygarh Deserves More Careful Attention

For a researcher or a traveller with patience, Vijaygarh offers something that more celebrated forts rarely provide: the chance to look closely at a place that sits in partial shadow, significant in its period, half-recorded in surviving documents, yet still carrying a layered account under every cracked stone.

It has served epic tradition, tribal settlement, Rajput ambition, regional kingship, Mughal administration, colonial revenue records, pilgrimage routes, and the pages of a beloved novel. It belongs completely to none of those roles. That is its most honest quality. Places of this kind outlive every label attached to them and go on standing, quietly and without ceremony, long after the purposes they were built for have changed or disappeared entirely.

Also Read:Agha Shah Dargah Holds Something Modern Life Has Almost Forgotten

You can connect with DNN24 on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel.