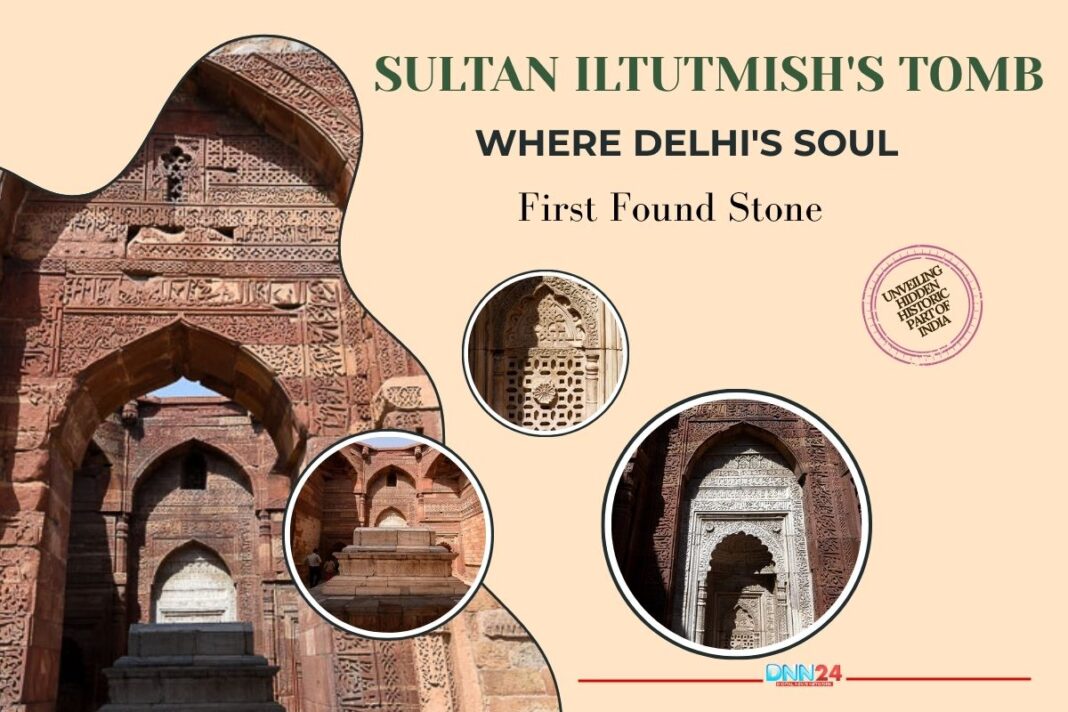

Sultan Shamsuddin Iltutmish’s tomb stands quietly in the shadow of the great Qutub Minar, yet its presence carries a weight that reaches far beyond its modest walls. Built in 1235 CE within the historic Qutub complex in Mehrauli, this red sandstone monument represents something remarkable in Indian history.

It is the first royal Islamic tomb ever constructed on Indian soil, marking the moment when rulers began to view death not as an end, but as an opportunity to leave behind beauty and memory. While many visitors flock to see the towering Qutub Minar nearby, those who pause at this square chamber discover a different kind of grandeur, one that speaks through silence, intricate carvings, and the story of a man who transformed himself from a slave to a sultan.

The tomb does not shout for attention. Instead, it invites reflection on power, mortality, and the meeting of two great civilisations. Within its weathered walls lies the beginning of a tradition that would shape Indian architecture for centuries, influencing everything from the grandeur of Humayun’s Tomb to the ethereal beauty of the Taj Mahal. This is where Delhi first learned to carve its rulers’ memories into stone, where Islamic architectural principles first blended with Indian artistic sensibilities, and where the language of memorial architecture was first written in this ancient land.

From Slave to Sovereign: The Extraordinary Journey of Iltutmish

The life of Shamsuddin Iltutmish reads like a tale that defies belief, yet history confirms every astonishing chapter. Born into the Ilbari tribe in the vast reaches of Central Asia, young Iltutmish knew the bitterness of slavery before he understood the concept of freedom. He was bought and sold multiple times, passed from master to master like common property, until fortune brought him to the court of Qutb-ud-din Aibak, the first Sultan of Delhi. There, his intelligence, military skill, and unwavering loyalty caught the eye of the Sultan, who eventually gave Iltutmish his daughter’s hand in marriage.

When Aibak died unexpectedly in 1210 CE during a game of polo, Iltutmish faced fierce opposition from rivals who questioned whether a formerly enslaved person deserved the throne. Yet by 1211 CE, through political acumen and military victories, he secured his position as the third Sultan of the Delhi Sultanate. His twenty-five-year reign transformed Delhi from a frontier outpost into the beating heart of northern India’s political and cultural life.

He introduced the silver Tanka and copper Jital coins, organised the Iqta land revenue system, and created the Chalisa, a council of forty loyal nobles who helped stabilise his rule. More importantly, Iltutmish received official recognition from the Caliph in Baghdad, legitimising the Delhi Sultanate in the eyes of the Islamic world.

Architectural Poetry Written in Red Sandstone

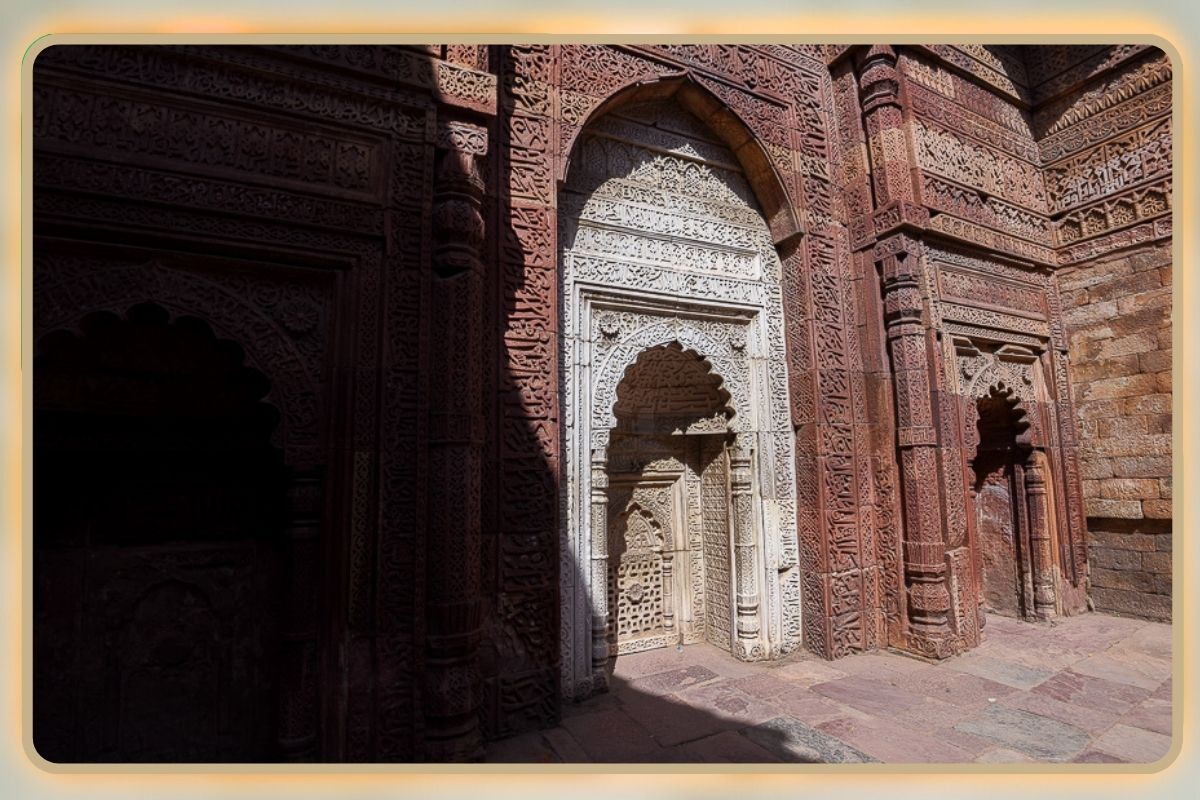

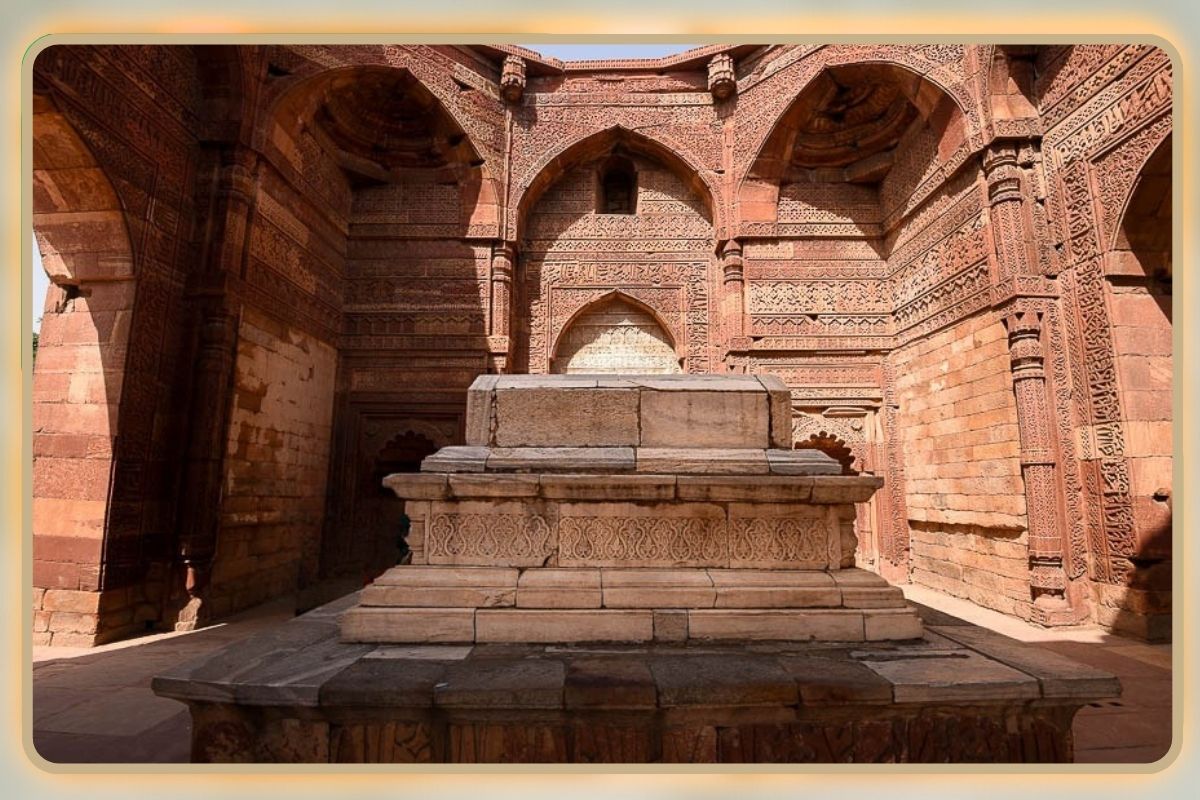

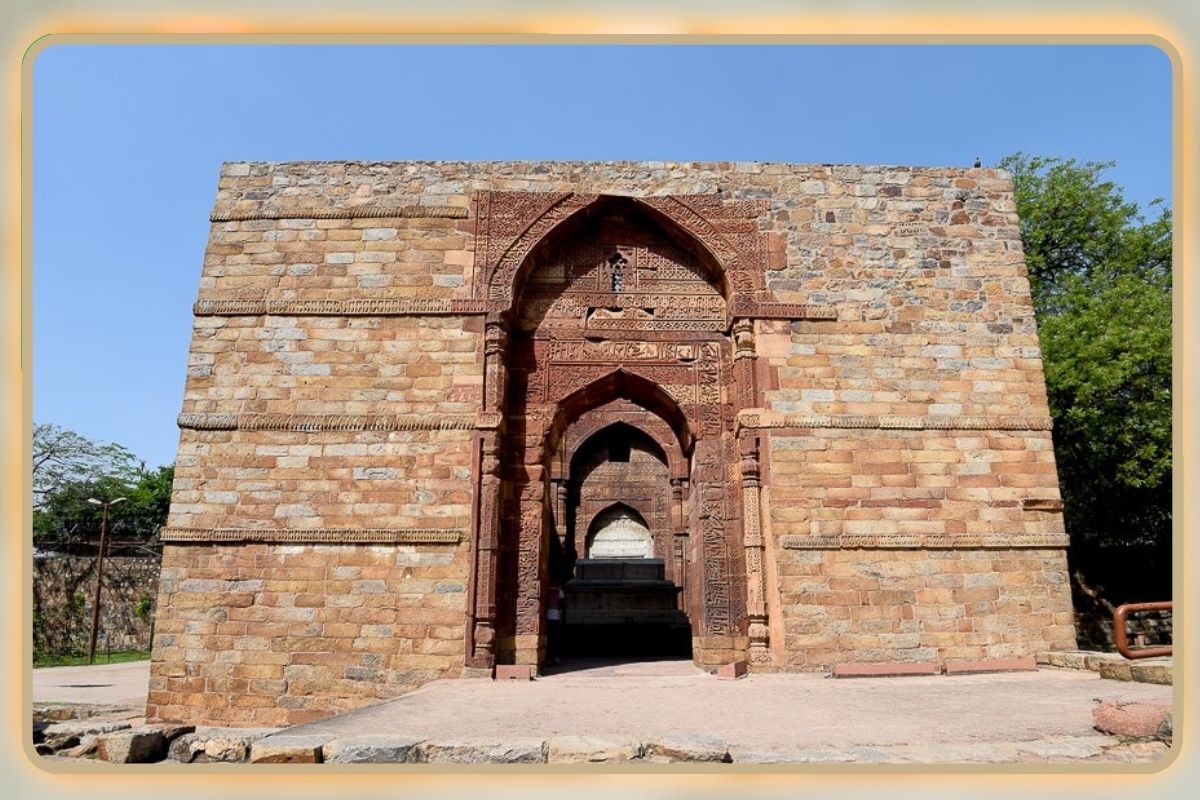

The tomb of Iltutmish reveals its beauty slowly, like a well-kept secret shared only with those patient enough to look closely. Constructed entirely from rich red sandstone quarried from the Aravalli hills, the building follows a simple square plan measuring approximately forty feet on each side. Three grand archways pierce the western, northern, and southern walls, each entrance framed with delicate carvings that demonstrate the skill of thirteenth-century artisans. The eastern fence stands solid, without any openings, oriented away from the qibla direction of prayer. Inside the chamber, the western wall features three mehrabs or prayer niches, with the central one distinguished by its gleaming white marble panels.

Initially, a magnificent dome crowned the structure. Still, it collapsed sometime during the fourteenth or fifteenth century, leaving the tomb open to the sky, a condition that somehow adds to, rather than diminishes, its spiritual character. Later rulers, including Firoz Shah Tughlaq in the fourteenth century, attempted restoration, but their efforts could not fully revive the original dome. Today, visitors enter a space where sunlight and rain fall equally on the cenotaph, creating an atmosphere of openness and humility. The interior walls carry the true treasure of this monument, intricate carvings that cover nearly every surface.

Where Two Worlds Met in Stone

The carved decorations inside Iltutmish’s tomb tell a fascinating story of cultural synthesis, revealing the moment when Islamic artistic traditions first encountered and embraced Indian creative genius. Quranic verses flow across the walls in elegant Arabic calligraphy, their sacred words offering prayers and reminders of mortality. Yet interwoven with these Islamic elements appear distinctly Indian motifs that would have been familiar to Hindu and Jain artisans of the period.

Lotus flowers bloom in stone corners, the same lotus that symbolises purity in Hindu and Buddhist traditions. Bell and chain patterns hang carved in relief, echoing designs seen in earlier Jain temples. Diamond-shaped tassels dangle decoratively, and the famous wheel and tassel motif appears prominently, borrowed directly from Hindu temple architecture.

This remarkable blending represents something more than mere decoration. The artisans who carved these walls were likely local artisans trained in traditional Indian techniques, now applying their skills to serve new patrons and new religious purposes. They did not abandon their ancestral artistic vocabulary but instead adapted it, creating something unprecedented, an Indo-Islamic style that would define North Indian architecture for centuries to come. The geometric patterns demonstrate Islamic preferences for abstract design, while the naturalistic floral work reveals Indian comfort with representing nature’s beauty. Together, these elements achieve a balance that neither conquers nor submits but finds harmony.

A Monument Among Monuments

Iltutmish’s tomb occupies sacred ground within the larger Qutub complex, surrounded by structures that collectively narrate the story of Delhi’s transformation from a Hindu kingdom to an Islamic sultanate. Just steps away stands the Quwwat-ul-Islam Mosque, constructed partly from materials taken from demolished Hindu and Jain temples, according to historical inscriptions, which mention twenty-seven temples. The towering Qutub Minar rises nearby, its red sandstone and marble storeys reaching toward heaven as a victory tower celebrating the establishment of Muslim rule in northern India. The Iron Pillar, dating back to the fourth-century Gupta period, stands as a testament to the region’s pre-Islamic heritage. Within this charged historical landscape, Iltutmish’s tomb strikes a different note.

While the Minar declares triumph and the mosque announces new religious authority, the tomb speaks of vulnerability and the universal human fate. Its relatively modest scale and the eventual collapse of its dome suggest an acceptance of impermanence. Iltutmish chose to build his final resting place here, among the monuments of power, yet his creation ultimately conveys a sense of humility. The tomb had a significant influence on subsequent Sultanate architecture. Balban’s tomb, built later in the thirteenth century, followed similar principles. Eventually, the tradition that Iltutmish began would reach its zenith in Mughal architecture, as seen in the magnificent tombs at Humayun’s complex and ultimately in the incomparable Taj Mahal.

Preserving Memory in Modern Delhi

Today, the Archaeological Survey of India maintains Iltutmish’s tomb as a protected monument, though it often receives less attention than its famous neighbours in the Qutub complex. Conservation efforts continue year after year, fighting against weather, pollution, and the simple passage of time that threatens all ancient structures. Workers carefully clean the red sandstone surfaces, removing biological growth and pollution deposits that obscure the delicate carvings. Structural monitoring ensures that the remaining walls remain stable despite the absence of the dome. Pathways around the monument receive regular maintenance, and informational plaques help visitors understand what they are seeing.

The tomb draws a diverse crowd, international tourists combine it with visits to the Qutub Minar, Indian school groups arrive for history lessons, architecture students sketch its arches and measure its proportions, and occasionally devotees come to offer prayers at this centuries-old grave. Photographers love the way afternoon light enters through the empty dome space, illuminating the prayer niches on the western wall.

On quieter days, the tomb offers something increasingly rare in bustling Delhi, a space for contemplation and connection with the distant past. The contrast between this ancient monument and the modern city surrounding it could not be starker. Beyond the complex walls, contemporary Delhi surges with energy, traffic, and the relentless push of development; yet, within these red sandstone walls, the pace slows, and centuries collapse into a single, eternal moment.

Also Read: Tomb of Bahlul Lodi: Delhi’s Hidden Sultan and His Humble Legacy

You can connect with DNN24 on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel.