Step off the highway near Malda, leave the tea vendors and bus rattles behind, and there it stands: a brick cube topped with a fat dome, catching the Bengal sun like a crown forgotten in the dust. This is the Eklakhi Mausoleum at Pandua, built somewhere between 1425 and 1431, and it holds three graves that whisper stories of power turned to dust. Most historians say Sultan Jalaluddin Muhammad Shah rests here with his wife and son, Shamsuddin Ahmad Shah, though a few still argue over whose bones lie beneath the floor.

The name Eklakhi comes from the one lakh rupees supposedly spent building it, a fortune back then, enough to feed villages for years. That price tag made this tomb more than just a grave; it became a bold announcement of wealth and grief carved in brick. Pandua, about 3 kilometres from the massive Adina Mosque, was once the roaring capital of the Bengal Sultanate. Now it breathes quietly, and this mausoleum feels less like a tourist spot and more like stumbling into someone’s private memory. The dome still watches over Bengal’s fields, and standing under it feels like the Sultan never really left, just moved into the walls.

Eklakhi Mausoleum: Pandua, Raja Ganesh and Jalaluddin’s Journey

Eklakhi cannot be understood without first knowing Pandua, and Pandua cannot make sense without Raja Ganesh. Between 1339 and 1453, this city served as Bengal’s capital, home to merchants, scholars, soldiers, and sultans, long before anyone cared about Dhaka. Raja Ganesh was a Hindu zamindar king whose word was law across late 14th- and early 15th-century Bengal. His son Jadu grew up in that Hindu royal household, but life had other plans for him. Jadu converted to Islam, changed his name to Jalaluddin Muhammad Shah, and became the first native Muslim Sultan of Bengal, also the last to rule from Pandua’s throne.

Why he converted remains a mix of power politics, religious pressure from outside forces, and survival instinct during a time when Bengal was caught between competing faiths and armies. His life became a mirror of Bengal itself: complicated, layered, never fitting neatly into one box. When Jalaluddin died around 1433, this mausoleum was supposedly waiting for him, turning the long road from Jadu to Jalaluddin into a silent monument about how identity in Bengal was always messy, constantly changing, always more than one thing at once.

Eklakhi Mausoleum: Architecture Like a Bengal Hut Turned into a Crown

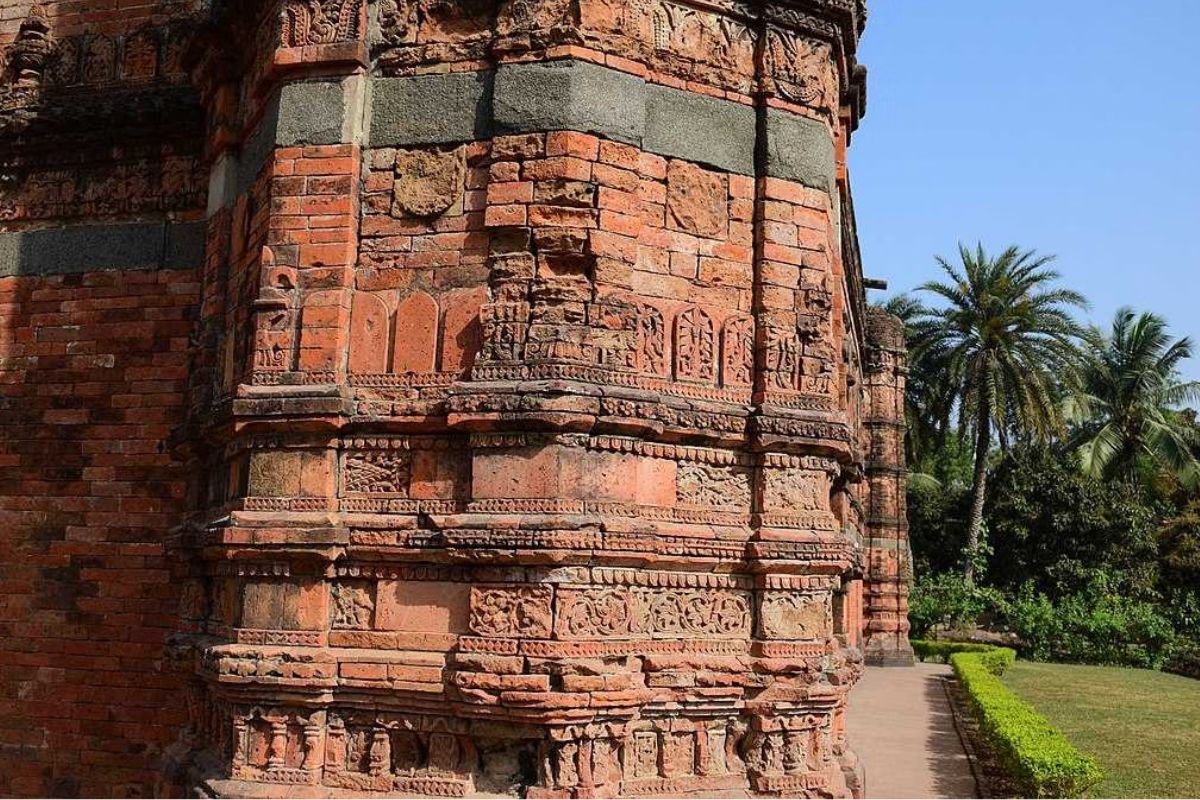

Walk up to Eklakhi and your first thought might be: this looks like a village hut, just bigger and made of brick. Yet it also feels royal, solid, permanent, like someone took a simple idea and stretched it into something grand. This is actually the oldest surviving square building with a single dome in Bengal, the first central square single-domed tomb here, a design that would get copied for generations. Built from red bricks on a base measuring roughly 25 by 23 metres, the walls are nearly 4 metres thick, thick enough to feel like a fort.

Step through the door, and the square room shifts into an octagon using squinches at each corner, letting a giant round dome float above your head without cracking. Each of the four walls once had arched openings, borrowed from the Persian chahartaq, those old four-doored fire temples, but reshaped to fit Bengal’s rains and soft soil. The curved cornice bends gently like a village thatch roof, helping rainwater slide off quickly, while terracotta and brick decorations feature only flowers and geometric patterns, no people or animals, keeping within Islamic rules. The whole building feels like a conversation between West Asian ideas and Bengali common sense, high art listening carefully to humble village construction.

Eklakhi Mausoleum: The Three Graves and a Quiet Debate

Inside the dim, cool chamber, three tombs lie next to each other like a family sleeping under one shared sky. Tradition says these are Jalaluddin Muhammad Shah, his wife, and their son Shamsuddin Ahmad Shah, who ruled Bengal briefly after his father died, carrying forward Raja Ganesh’s bloodline into the Islamic Sultanate. But some historians remain cautious, calling this identification “traditional” rather than a proven fact, reminding everyone that medieval Bengal rarely left clear name tags on its monuments.

Still, the three graves tell their own story even without labels: a ruler, the woman who knew his private worries, and the son who inherited both throne and trouble, all united in death under one dome. For anyone visiting today, this arrangement speaks louder than any inscription could. Personal life and public power were never separate back then. This tomb is not just about a Sultan; it is about a family, about love and loss turned into brick, about how even kings need someone to lie beside them when the world finally goes quiet.

Eklakhi Mausoleum: Shift from Gaur and the Birth of a Bengal Style

Eklakhi did not appear from nowhere. It grew out of a broader political and architectural shift across Bengal. Before Pandua, Gaur held all the power and all the grand buildings. When the capital moved, new experiments began, mixing local Bengali building methods with Islamic forms imported from Delhi and Persia. Eklakhi, with its square plan, single dome, engaged corner towers, and that distinctive curved cornice, became the blueprint for countless tombs and mosques built later across the Bengal Sultanate.

Scholars compare its layout to Iltutmish’s tomb in Delhi and to the old Persian chahartaq, but they also note how the builders adapted these ideas to address Bengal’s heavy monsoons and soft, shifting soil. That curved cornice, for instance, not only channels water away quickly but also echoes the shape of bamboo and thatch village roofs, proving that royal architecture was paying attention to how poor farmers kept rain out of their huts. Eklakhi sits at a crossroads: Gaur’s older traditions behind it, Pandua’s bold experiments surrounding it, and a fully Bengali Islamic architectural style growing from its foundations like new shoots from old roots.

Eklakhi Mausoleum: Today’s Relevance in a Fractured Time

In modern India, where television debates rage over religion, identity, and who belongs where, the Eklakhi Mausoleum stands quietly, offering a different conversation. Here lies Jadu, born a Hindu prince, buried as Muslim Sultan Jalaluddin Muhammad Shah, bridging two faiths, two political worlds, multiple identities in one lifetime. His tomb reminds us that Bengal’s history never divided cleanly along religious lines. Positioned between the Adina Mosque and Pandua’s green fields, this mausoleum becomes a classroom without walls, teaching about coexistence, conversion, compromise, and shared heritage through nothing but brick and silence.

For young travellers and content creators, Eklakhi offers something rare: a setting for thoughtful reels, reflective writing, or just sitting quietly while history seeps into your bones. That one lakh rupees built more than a royal grave; it built a lasting metaphor for Bengal’s layered soul. In an age obsessed with tearing things down and forgetting fast, the Archaeological Survey of India maintains these grounds, visitors keep coming, and this mausoleum refuses to be just a dead monument. It remains a living reminder that identities can shift, merge, evolve, and still stay beautifully, undeniably Indian.

Also Read: Tomb of Sher Shah Suri: An Emperor’s Dream Palace Floating On Water

You can connect with DNN24 on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel.