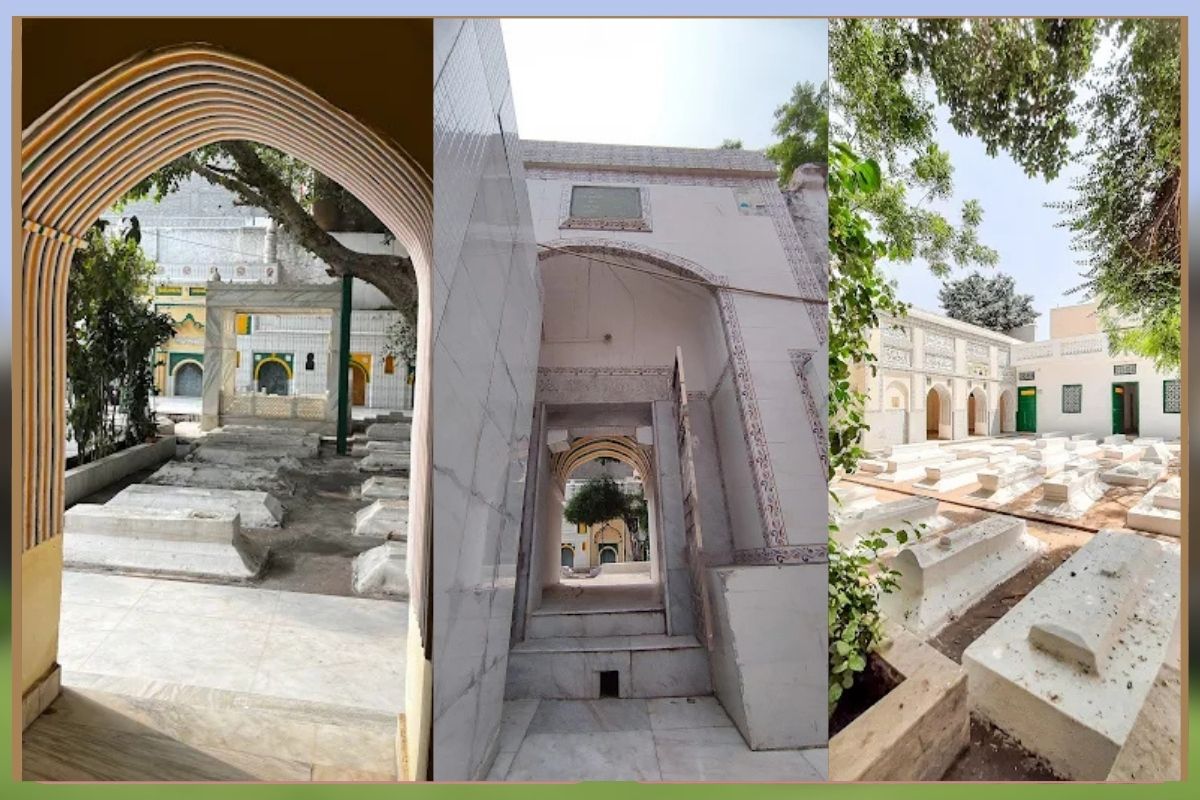

In the heart of South Delhi’s Mehrauli lies a monument that doesn’t scream for attention but quietly draws you in with its stillness, Hijron ka Khanqah. A world of serenity opens up through a simple green gate, where 49 whitewashed tombs rest in quiet dignity. At the centre lies the grave of Miyan Saheb, a leader among Delhi’s hijra community, whose memory continues guiding and inspiring generations. The space, built in the 15th century during the Lodi period, is not grand in scale or design, yet its aura surpasses many larger monuments.

It offers the hijra community a place of prayer and a sanctuary of belonging in a city that has often refused recognition. Since the 20th century, the community of Turkman Gate has been the custodian of this sacred space, tending to it with care and reverence. Unlike monuments that crumble under neglect, this khanqah has lived because of the love of those who see their history reflected in its walls. Every visit is more than a history lesson; it is an encounter with resilience, a reminder that spaces acquire soul when nurtured not just as stone, but as memory.

Echoes of the Lodi Era and Sufi Roots

Hijron ka Khanqah carries within it the fragrance of Delhi’s medieval past, particularly the days of the Lodi dynasty when Sufism flourished across northern India. In that period, khanqahs were not mere retreats; they were places of inclusivity, bringing together kings, commoners, mystics, and communities often pushed to the edges of society. The hijra community, known for loyalty and discretion, found respect in the courts of sultans as guardians, attendants, and sometimes trusted officials. Their identity, though different, was not always marked by stigma. The khanqah reflects this inclusiveness. Built as a Sufi retreat, it became a rare resting ground for the hijra community, enshrining their memory within Delhi’s spiritual geography.

The most prominent grave belongs to Miyan Saheb, remembered as a follower of the great saint Qutbuddin Bakhtiyar Kaki, among the most celebrated Sufis of Delhi. His presence at the khanqah strengthens its spiritual gravity, linking the space to Delhi’s larger Sufi traditions. The monument endured the fall of dynasties and the rise of new rulers, even as colonial rule reduced the hijra community to ridicule and marginalisation. Through all transitions, this khanqah remained, not as a grand fort or mosque, but as a quiet witness of resilience. Its white tombs are more than markers of the dead; they testify to a culture honing inclusion long before it became a modern debate.

Guardians of Tradition and Community Bonds

What keeps Hijron ka Khanqah alive is not government preservation but the guardianship of the hijra community itself. For decades, individuals like Kokila Haji and Shri Pal have taken the responsibility of maintaining the monument, sweeping its courtyard, painting its walls, and keeping its rituals alive. Their devotion reflects more than duty; it shows a deep bond between people and their sacred history. In a society that often strips the hijra community of dignity, the khanqah restores it by providing a space where they are not outsiders but rightful keepers of tradition. It is also a space where identity is celebrated rather than hidden. Generations gather here for prayers, storytelling, solidarity, and collective healing.

The rituals performed here bind the past with the present, weaving ancestors’ struggles into the hope of today. Visitors who step into the courtyard do not just find a historical relic; they find living voices that speak of endurance, faith, and acceptance. Every corner tells of continuity, reminding us that heritage is not only about preserving stone but about sustaining meaning. This intergenerational care, passed on through the hijra community, makes the khanqah unique. It is not frozen in time like many old monuments; it continues to evolve, absorb, and breathe, much like the community that nurtures it.

Festivals that Nourish the Soul

Twice a year, the quiet courtyard of Hijron ka Khanqah transforms into a vibrant celebration hub during Muharram and Shab-e-Baraat. These festivals bring together the community for spiritual rituals and acts of generosity and sharing. On Muharram, the hijra community gathers through the night, offering prayers and recitations to honour the martyrs of Karbala. The storytelling makes the rituals here distinctive; members openly share personal experiences of pain, joy, and resilience, blending their narratives with spiritual remembrance. Shab-e-Baraat, the night of forgiveness and charity, brings another dimension.

Large quantities of food, 30 kilograms of mutton, hundreds of rotis, and sweet halwa, are prepared and distributed to people experiencing poverty, keeping the Sufi tradition of langar. These gatherings are not mere rituals; they are acts of community building. They create a sense of belonging beyond the hijra community, embracing neighbours, visitors, and anyone who walks through the green gate. The festivals also remind us that charity is not about abundance but intent; feeding the hungry celebrates humanity. In these moments, the khanqah is more than a shrine; it becomes a living classroom, teaching lessons of equality, compassion, and the strength of collective spirit.

Festivals of Faith: Muharram and Shab-e-Baraat

Every year, the quiet of Hijron ka Khanqah is broken by the rhythm of devotion during Muharram and Shab-e-Baraat. These two occasions transform the khanqah from a silent sanctuary into a living arena of remembrance and generosity. On Muharram, the hijra community gathers under the night sky, sitting close to the tombs as verses are recited in memory of the martyrs of Karbala.

The gathering is about mourning and sharing stories of personal struggles, whispers of resilience, and prayers that tie past and present into one unbroken thread. Unlike the more formal processions in Delhi, the rituals are intimate, woven with tears and laughter, and storytelling as sacred as the prayers. Shab-e-Baraat, however, is a night of abundance and charity.

Massive pots bubble with meat and rotis, and the air fills with the sweet smell of halwa. Thirty kilograms of mutton and hundreds of flatbreads are prepared, not for feasting but for distribution, food passed with affection to people experiencing poverty who gather at the gates. The act is deeply Sufi in nature: feeding the hungry to feed the soul. These festivals keep the khanqah rooted in continuity. Every prayer recited, roti shared, and story told ensures that the space does not fade into lifeless stone but thrives as a heart that beats with grief and joy. For the hijra community, these observances are not just traditions but acts of survival, belonging, and self-affirmation.

Unique Rituals of Muharram at the Khanqah

Muharram at Hijron ka Khanqah carries a rhythm unlike anywhere else in Delhi. The rituals here do not follow the grandeur of large imambadas or the solemnity of public processions; instead, they are steeped in intimacy, adapted to the spirit of the hijra community. The courtyard becomes a theatre of memory where voices rise not in chorus but in overlapping cadences, each mourner carrying their personal grief into the collective. No ornate tazias or grand alams dominate the space. Instead, simple symbols, candles flickering near the tombs, verses softly recited under breath, and the slow thump of hands on the chest create a raw and profoundly moving atmosphere. What makes these rituals unique is their inclusivity.

The hijra community opens the doors of the khanqah to neighbours, travellers, and anyone who wishes to sit in remembrance. People share food, stories, and silences, blurring boundaries of religion and identity. Muharram here is not only about recalling the tragedy of Karbala but also about recognising suffering in all its forms, such as social rejection, personal loss, and the longing for dignity.

For the hijras, every act of mourning becomes an act of defiance: a refusal to be erased from history or denied a place in devotion. In this sense, the rituals are both spiritual and political. They reaffirm the khanqah as a sacred space where grief is transformed into solidarity, and marginalisation is answered with remembrance. Muharram at Hijron ka Khanqah is thus not just a ritual; it is resilience performed year after year, stitching a community into the fabric of Delhi’s spiritual life.

A Living Poem of Memory and Hope

Hijron ka Khanqah is not just about old stones and fading inscriptions but about the spirit that breathes through them. Every tomb holds an unspoken history, stories of those who lived on the margins yet carved a place for themselves in the city’s spiritual memory. For the hijra community, the khanqah is both a memorial and a site of transformation. It strengthens them to reclaim their past, honour their ancestors, and find renewed meaning in their present. In a fast-changing city like Delhi, where modernity often erases traces of the old, the khanqah stands as a gentle teacher. It tells us that genuine respect lies not in labels but in recognition of humanity.

Its guardians continue weaving medieval wisdom with modern challenges, making the space a beacon of hope. Visitors who enter its courtyard leave not with nostalgia alone, but with a renewed understanding of what inclusion and dignity mean. The khanqah is, in many ways, a living poem, each line written in stone, each stanza echoing resilience, and each verse urging society to build bridges instead of boundaries. It remains a monument of the past and a conversation with the future, reminding India that acceptance is not charity but justice, and that memory, when honoured, becomes the foundation of hope.

Also Read: Adham Khan’s Tomb: The Maze of Betrayal and the Price of Power

You can connect with DNN24 on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel.