Ghiyas-ud-din Tughlaq’s tomb stands quietly at the edge of modern Delhi, a stone witness to the centuries of change that have unfolded since its construction. This ancient monument, surrounded by fortress walls and layered with history, draws not only scholars and photographers but also anyone curious about the stories that have shaped India’s capital.

Unlike the ornate structures that would follow centuries later, this tomb speaks a different language, one of strength, practicality, and survival. Built during the 14th century, it represents a unique chapter in Delhi’s architectural journey, where the need for protection shaped even the resting places of kings. The structure remains a powerful reminder that history lives not just in books but in every weathered stone and arched doorway.

Visitors today find themselves walking through more than just an old building; they step into a moment frozen between medieval power struggles and contemporary urban sprawl. The tomb is situated adjacent to the Tughlaqabad Fort, accessible via an ancient causeway, although modern roads have disrupted this historic link. What makes this monument particularly fascinating is that it defies expectations; it refuses to be simply beautiful or simply functional, instead existing as both shelter and symbol. For anyone seeking to understand Delhi beyond its busy streets and modern monuments, this tomb offers a quiet invitation to pause and remember.

The Sultan Who Built to Last

Ghiyas-ud-din Tughlaq, born as Ghazi Malik, rose from military ranks to establish the Tughlaq dynasty in 1320. He took control of the Delhi Sultanate after the chaotic years of Khilji rule, bringing with him a reputation for discipline and strategic thinking. His primary concern was not artistic legacy but survival; the Mongol invasions that threatened northern India demanded strong walls and fortified cities. This practical mindset led him to construct Tughlaqabad Fort, a massive defensive complex meant to protect his subjects and establish his power. The Sultan commissioned his own tomb during his lifetime, a common practice among rulers who wanted control over their final resting place.

His choice to build something that resembled a fortress more than a mausoleum reflected his personality and priorities throughout his reign. Tragically, his life ended suddenly in 1325 during a reception in Afghanpur, hosted by his son Muhammad bin Tughlaq. Historians continue to debate whether the pavilion’s collapse was accidental or orchestrated, but the mystery only adds depth to the Sultan’s legacy. What remains undisputed is his impact on Delhi’s landscape, the fort and tomb stand as permanent records of his vision.

The causeway connecting the tomb to Tughlaqabad Fort once allowed royal processions to move between residence and memorial, a physical link between living power and eternal rest. Today, that fort lies mostly in ruins, overrun with vegetation and scattered stones. Yet, the tomb endures with remarkable integrity, perhaps fulfilling the Sultan’s wish for something that would truly last.

Stone Walls That Tell Stories

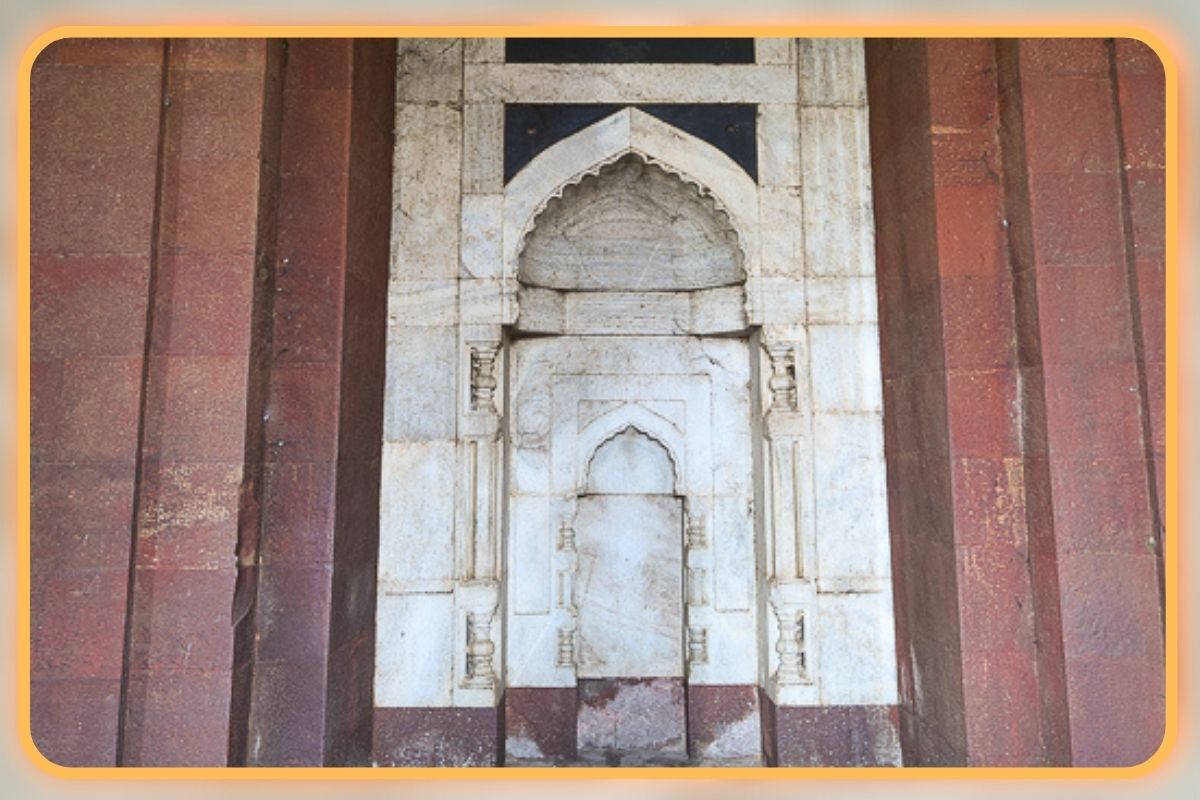

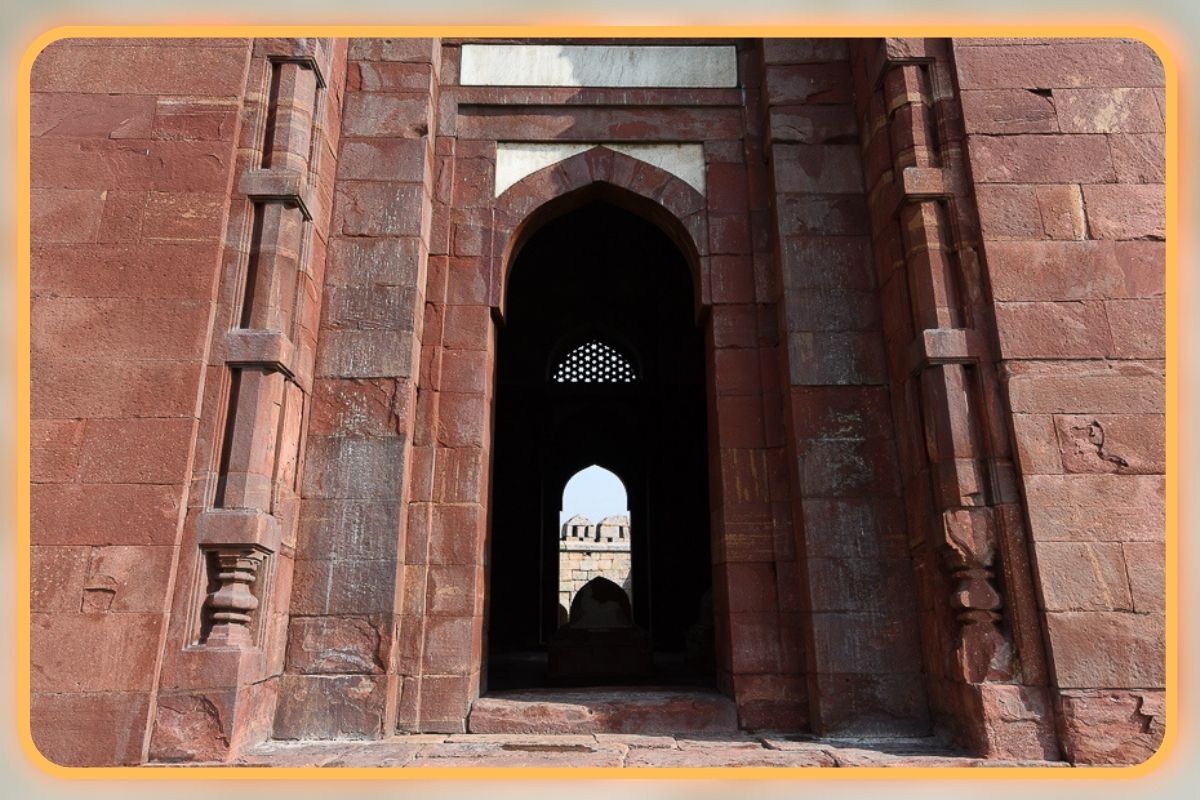

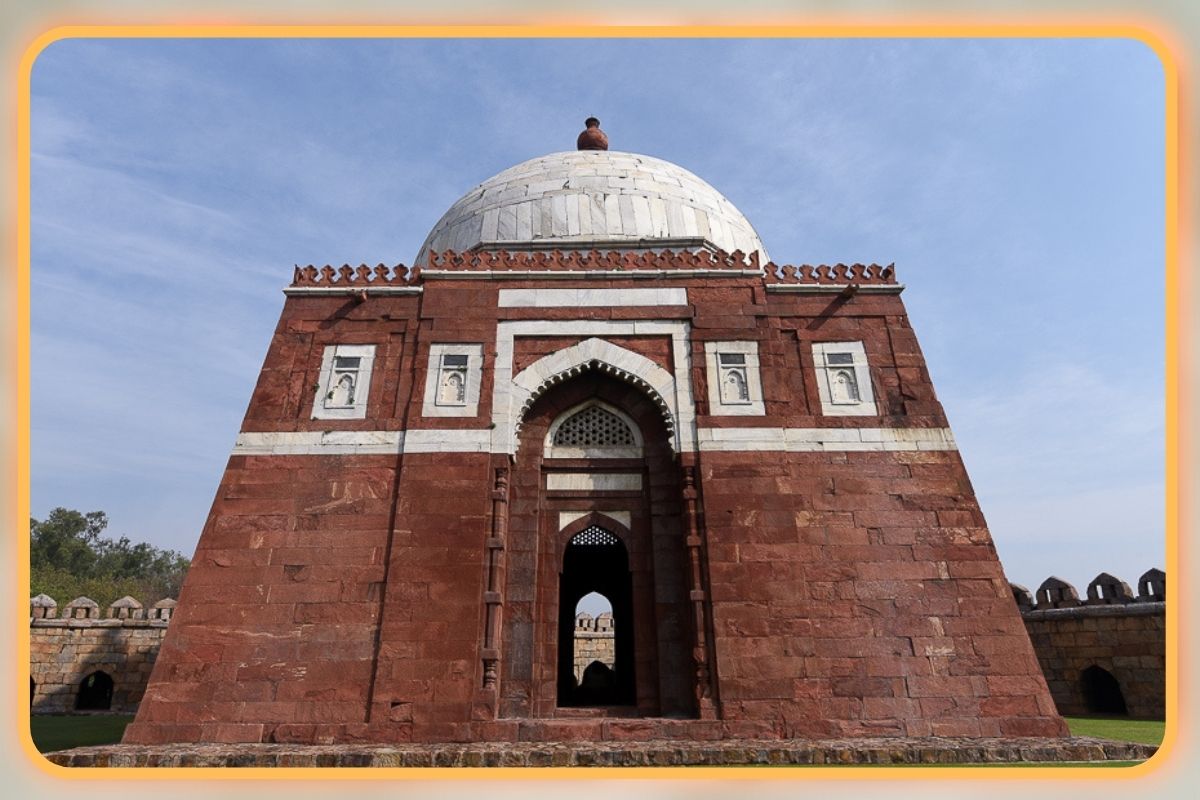

The tomb’s architecture immediately announces its defensive character; its thick walls slope inward, like the fortifications of a bastion, and the exterior is dominated by red sandstone. White marble provides contrast, used selectively for decorative elements and the dome that crowns the octagonal structure. A lotus finial sits atop the dome, an unexpected Hindu architectural element in an Islamic monument, highlighting the cultural blending that characterised medieval India. Three arched entrances allow access to the tomb chamber, while a mihrab on the western wall transforms part of the structure into a functional mosque.

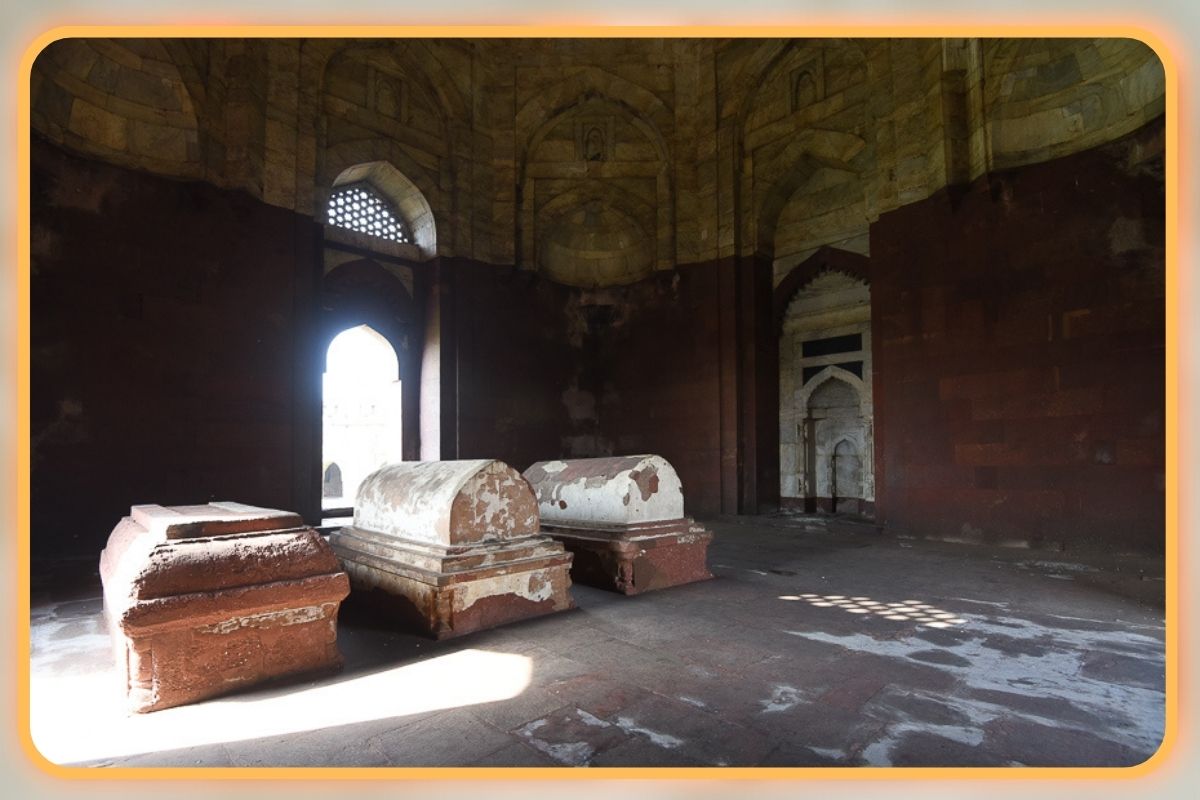

This combination of tomb and prayer space was typical of Indo-Islamic architecture, where the sacred and the memorial coexisted naturally. Inside the chamber, three graves mark the resting places of Ghiyas-ud-din, his wife Makhdum-i-Jahan, and his son Muhammad bin Tughlaq, the very ruler whose reception ended the founder’s life. The tomb’s sloping walls serve both aesthetic and structural purposes, distributing the weight of massive arches while visually connecting the building to surrounding fortifications. Ornamentation remains minimal by later Mughal standards, carved pillars, marble inlay work, and decorative battlements provide just enough detail to break the severity of the stone surfaces.

The pentagonal enclosure surrounding the tomb adds another layer of defensive architecture, creating a protected space within a protected space. Just outside stands a smaller octagonal tomb belonging to Zafar Khan, a trusted general from the previous Khilji dynasty, representing the continuity of Delhi’s political history. The design shows evident influences from earlier temple architecture, particularly in the lotus dome and stone lintel work, proving that architectural traditions crossed religious boundaries more freely than political ones. What strikes visitors most is the restraint this monument refuses to shout or overwhelm; instead, it makes its statement through solid presence and thoughtful proportion.

A Monument Living in Modern Times

Today, Ghiyas-ud-din Tughlaq’s tomb serves purposes its builder never imagined. School groups arrive regularly, with children running across the grass while teachers explain the sultanate’s politics and architectural terminology. Photographers seek the perfect angle as afternoon light catches the marble dome against Delhi’s hazy sky. Residents use the grounds for evening walks, treating the historic enclosure as both a neighbourhood park and a heritage site. The tomb attracts architecture students who study how early Tughlaq design differs from what came before and after, tracing the evolution of Indo-Islamic building traditions through specific details, such as arch shapes and wall treatments.

Heritage enthusiasts debate conservation approaches, weighing the need to preserve original materials against the practical requirements of maintaining a 700-year-old structure exposed to weather and pollution. The causeway that once connected the tomb to the fort was severed when the Mehrauli-Badarpur Road was cut through, a stark reminder that modern infrastructure often disrupts historical continuity. Yet this interruption itself tells a story about how cities grow and change, sometimes preserving their past and sometimes sacrificing it to present needs.

Tour guides blend historical facts with local legends, offering visitors a mix of documented events and folkloric embellishments that have accumulated over centuries. The tomb has become a popular backdrop for creative projects, serving as inspiration for writers seeking to capture the essence of old Delhi, artists sketching architectural details, and filmmakers capturing the atmosphere of medieval power translated into stone. What makes the monument particularly relevant now is how it challenges contemporary Delhi to reconsider its relationship with history, asking whether heritage sites should remain isolated exhibits or integrate more fully into daily urban life.

Echoes That Reach Forward

The tomb of Ghiyas-ud-din Tughlaq offers lessons that extend beyond architecture and history. Its fortress character speaks to a ruler who understood that security and beauty need not contradict each other, that strength can take elegant forms. The blend of Hindu and Islamic elements demonstrates how cultural exchange happened through craft traditions and shared aesthetic sensibilities, regardless of political divisions. Its location, once central to sultanate power, now peripheral to sprawling Delhi, illustrates how cities shift their centres over time, leaving monuments to mark old boundaries and former priorities.

The tomb stands as physical evidence that what seems permanent changes constantly, that forts crumble. At the same time, memorial structures endure, and ambitious rulers who build to defend everything often leave behind only their graves and the stories surrounding them. For modern visitors, the site offers a rare quietness in a loud city, a place where stone walls block out traffic noise and busy thoughts equally well. It reminds us that history is not abstract but physical, built by actual people who worried about invasions and family loyalty, who commissioned buildings and died unexpectedly, leaving others to interpret their intentions.

The monument invites reflection on how we remember leaders, through their military victories, their building projects, their family dramas, or simply through the fact that their tombs still stand when so much else has disappeared. In a metropolis racing toward its future with glass towers and metro lines, Ghiyas-ud-din Tughlaq’s fortress tomb anchors one corner to the past, asking Delhi and its residents to carry forward the stories embedded in every arch and every weathered stone surface.

Also Read: Tomb of Alauddin Khilji: Delhi’s Silent Monument of Power and Learning

You can connect with DNN24 on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel.