What if the greatest emperor’s power began not in a palace, but at his father’s grave?

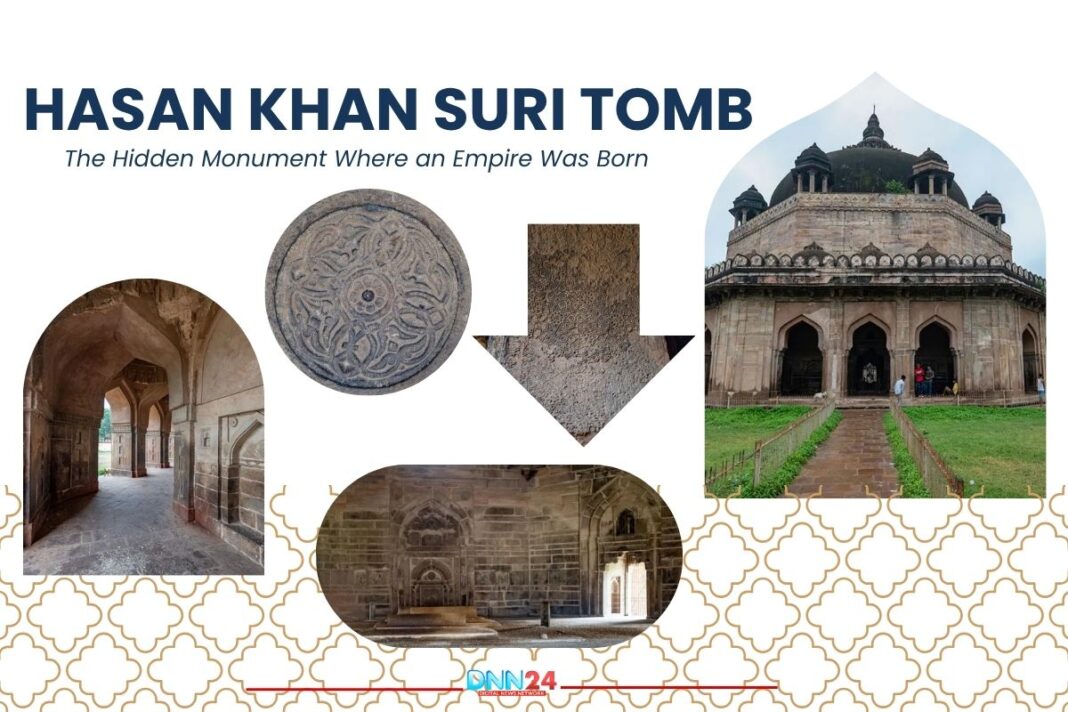

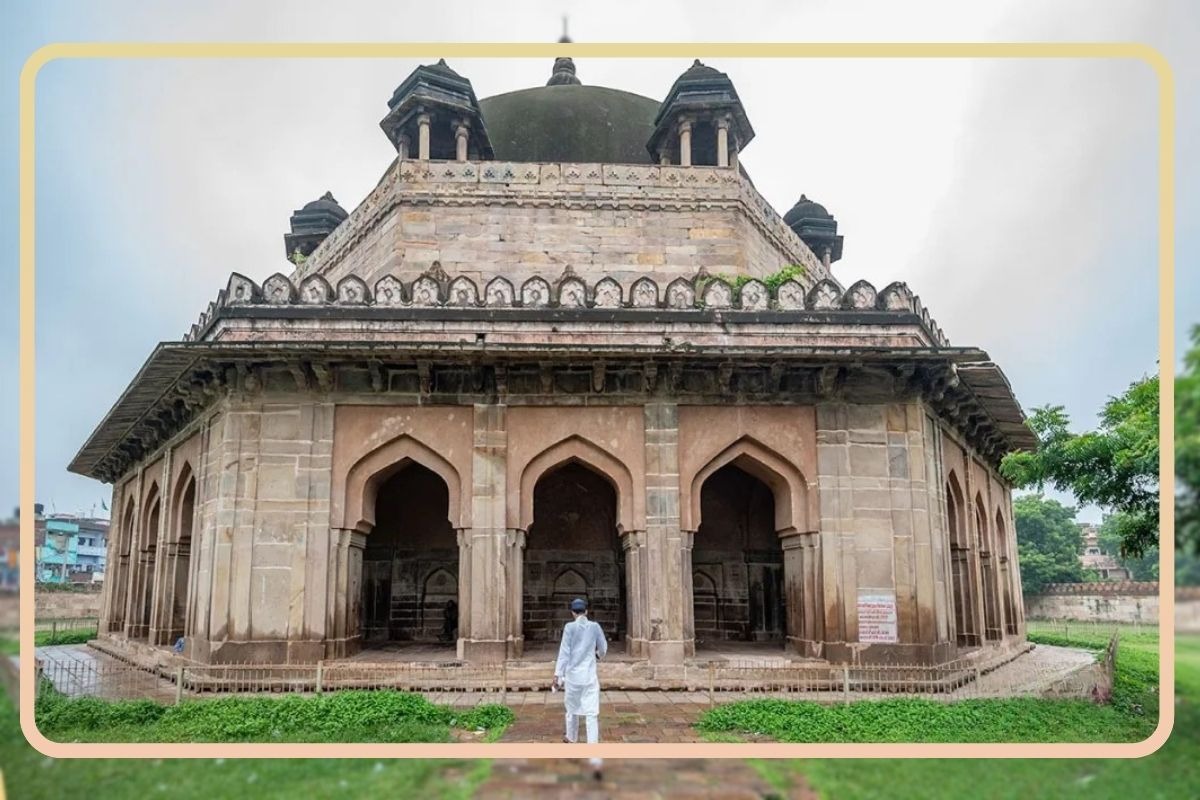

Deep in the heart of Sasaram, Bihar, stands a monument that most tourists rush past without a second glance. They are heading to the grand mausoleum by the lake, the one with marble gleaming in the afternoon sun. But they miss something remarkable. The Hasan Khan Suri Tomb, also known as Sukha Rauza or the “dry tomb”, holds secrets that shaped one of India’s most efficient empires. This is not just another mediaeval structure. This is where Sher Shah Suri, the emperor who challenged the Mughals and built the Grand Trunk Road, honoured his father with stone and devotion. Built around 1535, this octagonal wonder combines Afghan architectural traditions with Indian craftsmanship in ways that still puzzle historians today.

The Man Behind the Monument

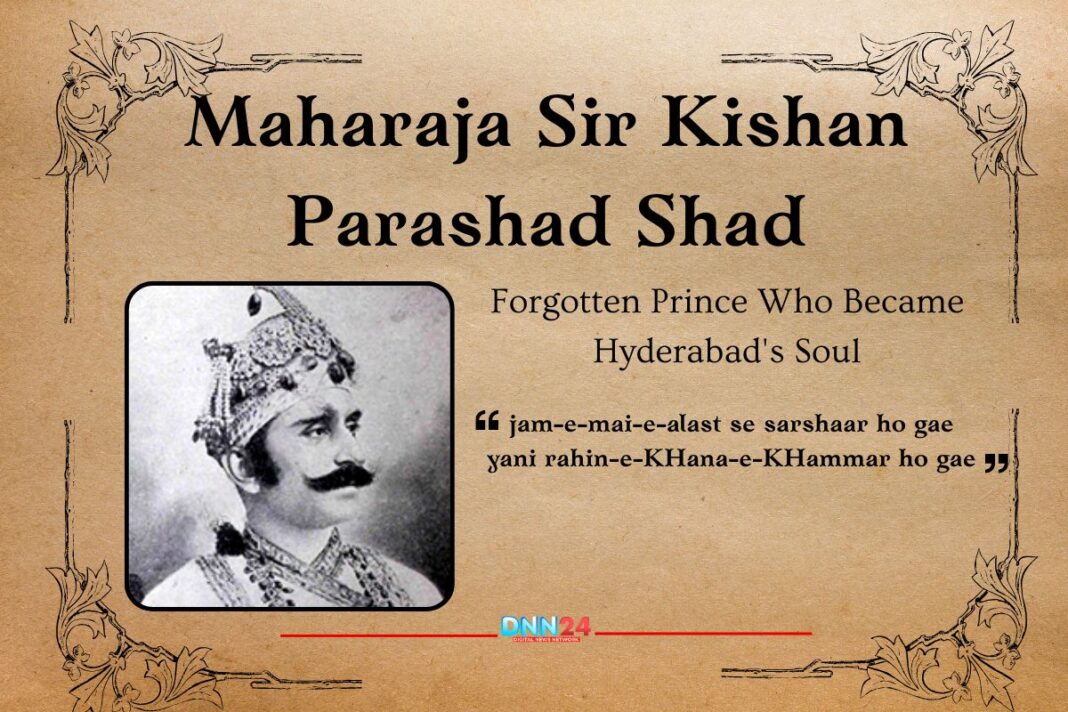

Hasan Khan Suri was no ordinary man, though history often forgets him in the shadow of his famous son. He served as a jagirdar under the Lodi dynasty, managing lands and people during one of mediaeval India’s most turbulent periods. His family had travelled from Afghanistan to settle in the plains of Bihar, bringing with them traditions, ambitions, and survival instincts sharpened by generations of political upheaval. When Hasan Khan died around 1526, the world barely noticed. He was just another nobleman in a time when empires rose and fell like seasons.

But his son Sher Shah noticed. After defeating Humayun and claiming the title of Sultan, Sher Shah did something extraordinary. He did not build his father a simple grave marker. He commissioned architect Aliwal Khan to create a tomb worthy of imperial lineage. This was not just about love or duty. This was a political statement written in sandstone and mortar. By elevating his father’s memory, Sher Shah was declaring that the Suri dynasty deserved its place among India’s ruling families. The tomb became proof that the Suris were not upstarts or temporary rulers but a family with roots, history, and legitimacy.

The construction reflected both personal devotion and dynastic ambition. Every arch and dome announced to rival kingdoms that Sher Shah’s authority came not from conquest alone, but from heritage. The tomb sits within a square walled enclosure, surrounded by a functioning mosque and an ancient stepwell. These were not decorative additions. They served the living community, ensuring that Hasan Khan’s memory remained woven into daily life rather than isolated in royal remembrance.

Architecture That Speaks Without Words

The first thing that strikes visitors is how different this tomb feels from typical Mughal architecture. There is no artificial lake, no grand causeway, and no elaborate gardens. The structure rises from the earth with quiet confidence, its grey sandstone walls weathered by centuries of Bihar’s monsoons and summers. The octagonal design, a signature of Afghan tomb architecture, creates eight equal faces, each featuring three arched openings. These are not random choices. The octagon symbolises the connection between the earthly square and the divine circle, a concept shared across Islamic architectural traditions.

The central dome crowns the structure, surrounded by smaller ornamental chhatris that add grace without overwhelming the design’s simplicity. Walk through any of the arched gates, and you enter a single-storey verandah that circles the inner chamber. The space feels intimate rather than imposing. Light filters through the arches in geometric patterns that shift throughout the day, creating shadows that dance across the floor where Hasan Khan’s grave rests. The ceiling inside shows traces of what must have been beautiful decoration once, though time has worn away most details.

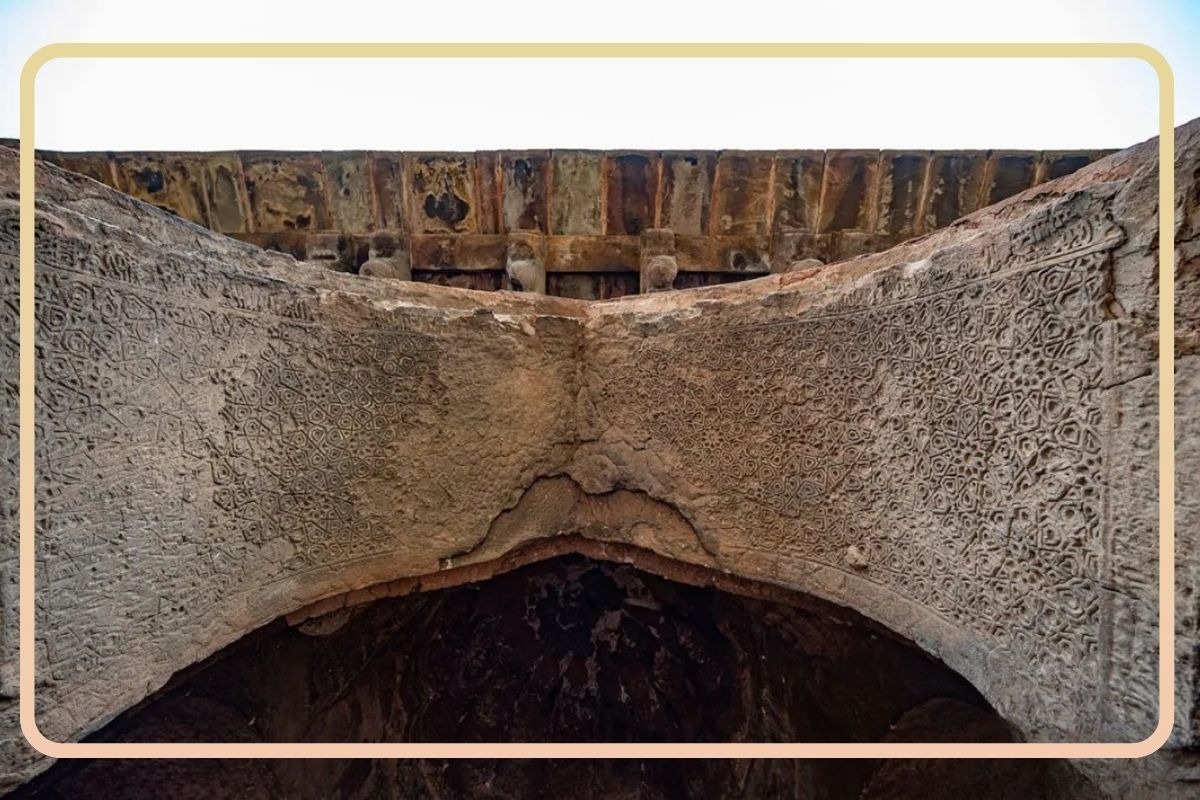

What makes this tomb architecturally significant is how it blends influences. The Afghan octagonal form meets Indian craftsmanship in the detailed stonework. The proportions follow mathematical principles that ensure visual harmony from every angle. Unlike many tombs that dominate their surroundings, this one sits comfortably within its enclosure, as if in conversation with the mosque and stepwell rather than commanding attention. The western wall of the mosque contains a mihrab with inscriptions in Naskh script, one of the few remaining clues about the tomb’s construction and purpose.

Modern architects and historians study this tomb because it represents a transitional moment in Indian architecture. It stands between the Delhi Sultanate styles and what would later become Mughal refinements. You can see experiments here, ideas being tested that would appear in more famous monuments decades later. The simplicity is deceptive. Every measurement, every angle, every arch represents a sophisticated understanding of structure, aesthetics, and meaning.

Stories Carved in Stone

The inscription above the mosque’s mihrab tells us that Sher Shah built this tomb after becoming Sultan as an act of remembrance for his father. But monuments speak louder than words. The choice to build in Sasaram rather than a more prominent capital city reveals Sher Shah’s connection to his roots. This was his homeland, the place where his father had established their family’s presence. By building here, Sher Shah was honouring not just a man, but a journey, a struggle, and a family’s rise from Afghan origins to Indian sovereignty.

Local people in Sasaram have their own stories about the tomb. Some say that on certain evenings, you can hear whispers in the verandah, though it is probably just wind through the arches. Others talk about how their grandparents remembered when the stepwell still provided water to travellers, when the mosque hosted regular prayers, and when the tomb was not yet protected by archaeological surveys but was simply part of the neighbourhood. These oral histories add layers that official records miss.

The tomb also tells the story of preservation and neglect. Unlike Sher Shah’s own magnificent tomb nearby, which attracts tourists and receives regular maintenance, Hasan Khan’s tomb often sits quietly with minimal visitors. Guards sometimes absent themselves for hours. Weeds grow in corners that should be swept. Yet the structure endures. The Archaeological Survey of India maintains it under protected monument status, ensuring that even if public attention wanders, the physical fabric remains intact for future generations.

What strikes thoughtful visitors is the contrast between this tomb and its famous neighbour. Sher Shah built his own mausoleum in the middle of an artificial lake, a grand statement visible from a distance. But his father’s tomb speaks softly and requires you to approach, to enter, to pause and listen. Perhaps this difference reveals something about Sher Shah himself, his understanding that different kinds of respect require different expressions.

Why This Tomb Still Matters

In twenty-first-century India, where new construction rises faster than memory, old monuments face an identity crisis. Are they tourist attractions? Educational resources? Sacred spaces? Community property? The Hasan Khan Suri Tomb embodies all these roles without fully committing to any single one. Historians value it as evidence of architectural evolution. Students study it in courses about Indo-Islamic architecture. Locals consider it part of their neighbourhood landscape. The occasional tourist stumbles upon it while visiting Sher Shah’s tomb and discovers unexpected beauty.

The monument’s real significance lies in what it represents about legacy and memory. Sher Shah ruled for only five years before dying in battle, yet he accomplished administrative reforms that even Akbar, the great Mughal emperor, chose to continue. The Grand Trunk Road, postal system, standardised currency, and land revenue reforms all originated during Sher Shah’s brief reign. Yet he took time to build this permanent memorial to his father. This tells us something important about how he understood power and responsibility.

Today, the tomb serves as a reminder that history consists of layers. The famous stories get retold endlessly, while quieter narratives wait patiently for someone to notice. Hasan Khan Suri was not a sultan or a great warrior. He was a father who raised an exceptional son. The tomb his son built transforms that ordinary relationship into something monumental, suggesting that sometimes the most important historical figures are those who shaped the shapers of history.

Standing in the verandah of Hasan Khan Suri’s tomb, you can almost feel the weight of choices made centuries ago still pressing against the present. Every empire starts somewhere, with someone, often in places far humbler than history books suggest. This grey sandstone octagon in Sasaram is not just about one man’s death or one son’s devotion. It is about how we remember, what we choose to preserve, and why some stories deserve telling even when they do not come with crowds or glory attached.

Also Read: Tomb of Sher Shah Suri: An Emperor’s Dream Palace Floating On Water

You can connect with DNN24 on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel.