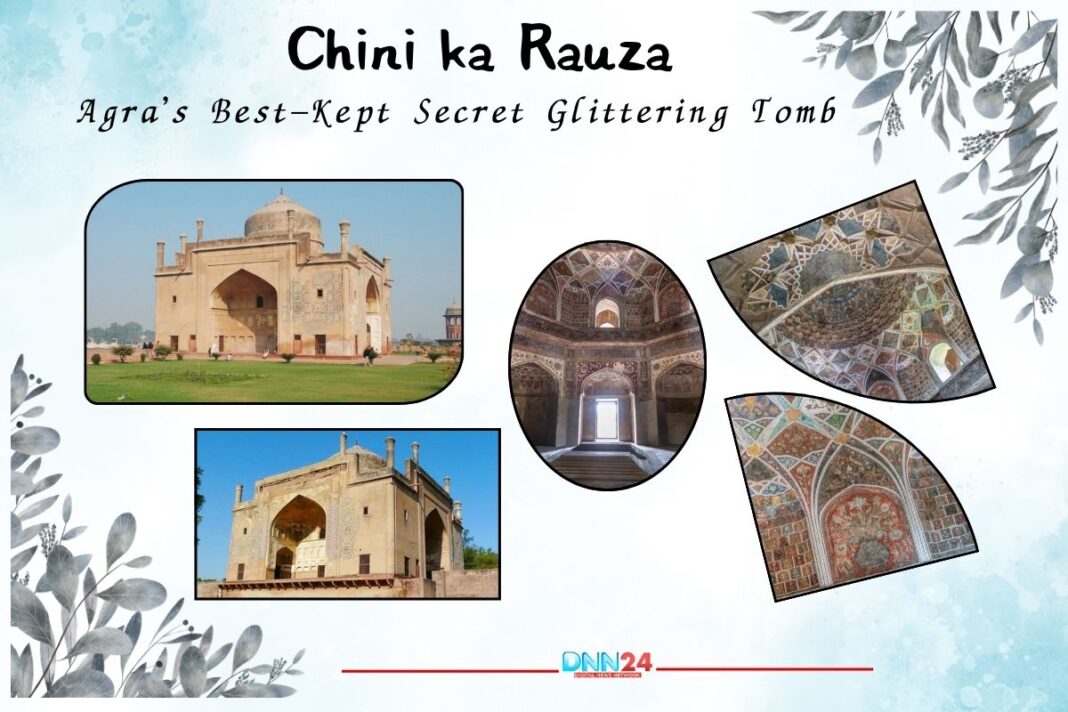

Most people rush past it without a second glance. While tourists flock to the Taj Mahal by the thousands, another tomb sits quietly on the opposite bank of the Yamuna River, fading into obscurity. Chini ka Rauza was once covered in tiles so brilliant they could be seen sparkling from across the water. Built in 1635 for Afzal Khan Shirazi, the powerful prime minister and poet under Shah Jahan, this mausoleum tells a story that few people know.

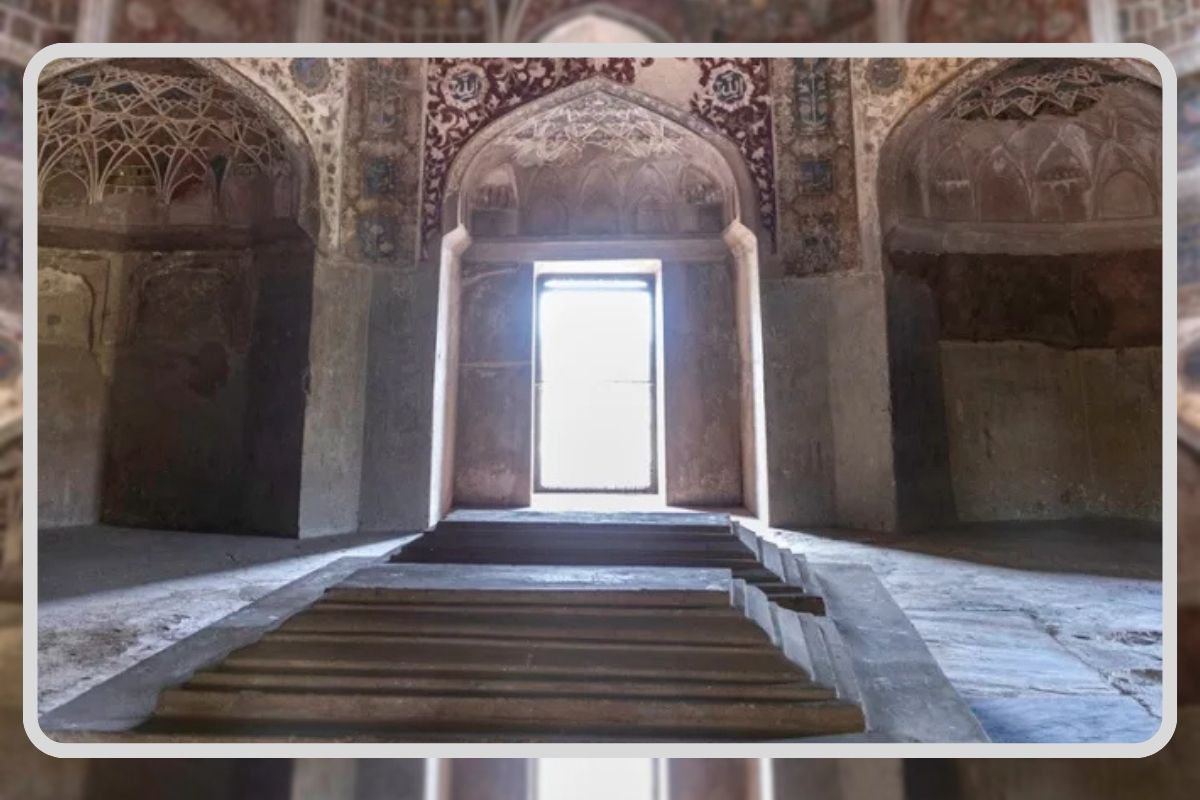

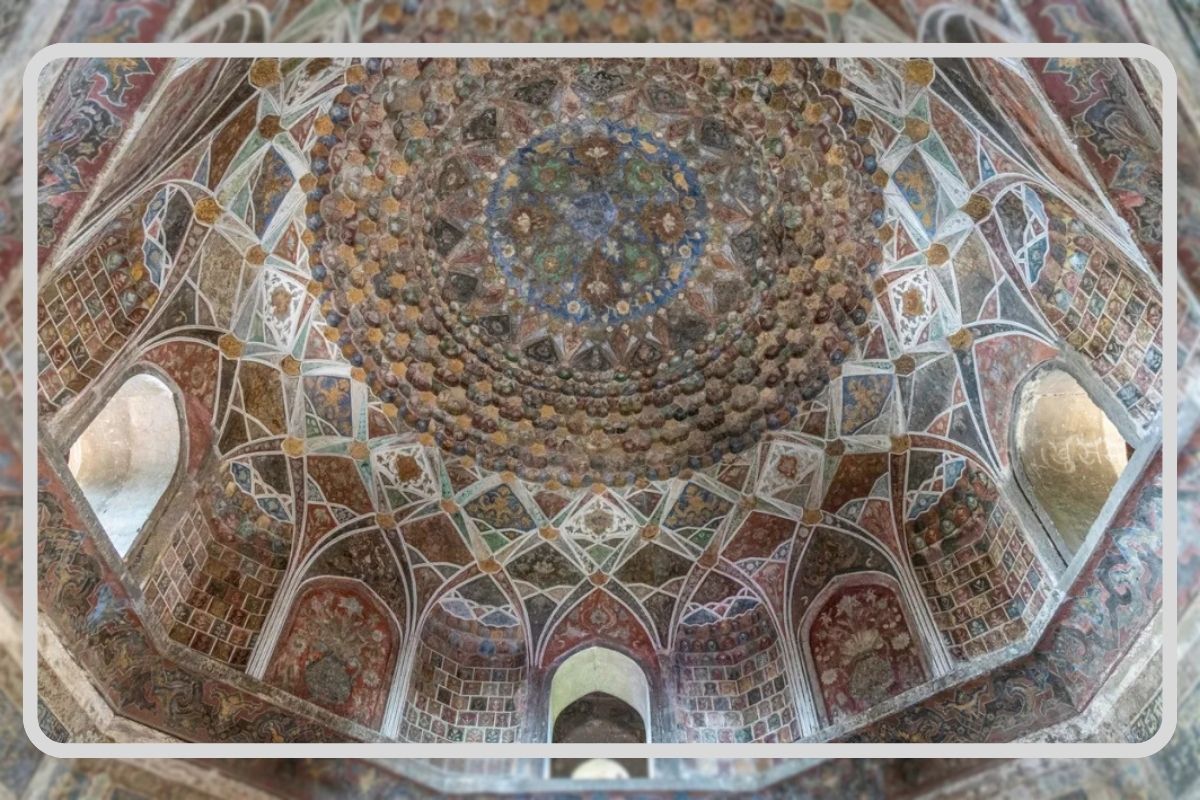

The name translates to “China’s Tomb,” and there is a reason for that. The entire structure was once adorned with glazed tiles imported from China, creating a dazzling display of blues, greens, and yellows that caught the sunlight in ways no other monument in Agra could match. The design itself is a blend of Persian and Indian architecture, with a square base supporting a graceful dome.

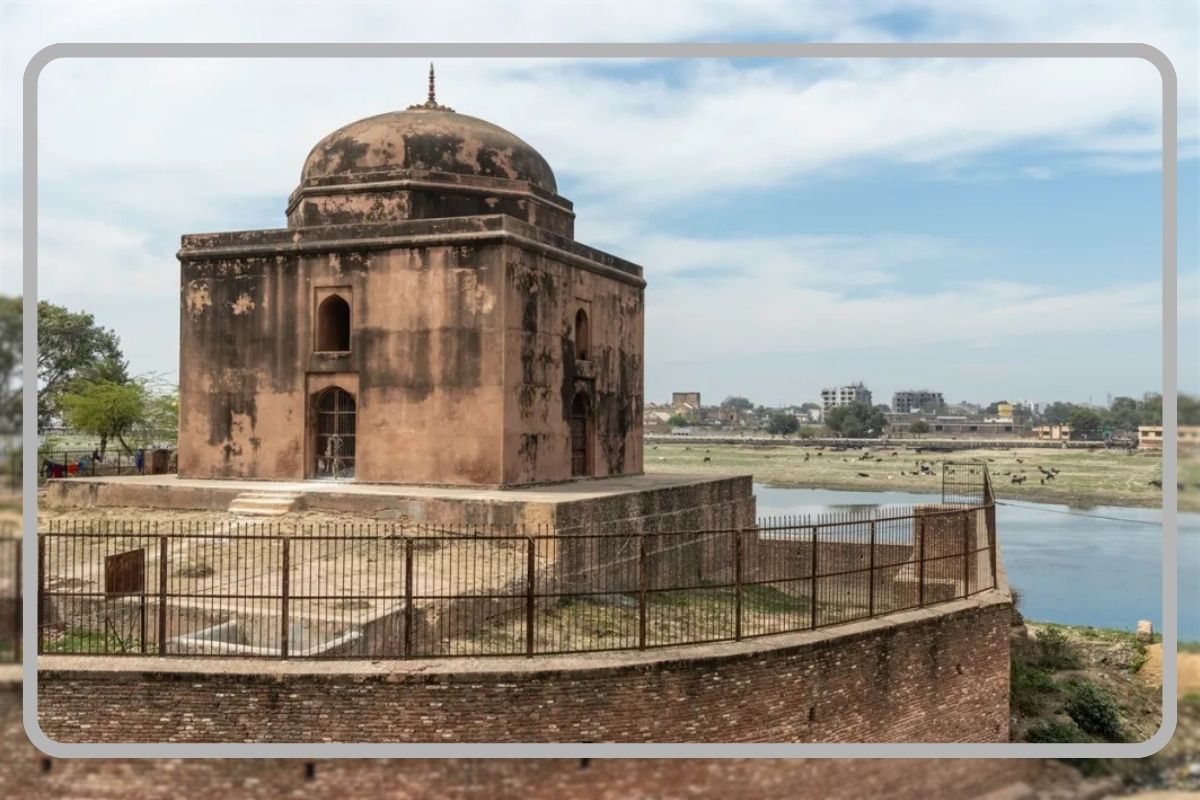

Today, the tiles have mostly vanished or dulled with time, stolen by looters or worn away by centuries of weather. But standing before it now, you can still sense the grandeur that once was. The tomb faces Mecca, built according to Islamic tradition, and its position by the river gives it a peaceful, almost melancholy presence. This is not just another Mughal monument. It is a window into a world where art and politics danced together, where poetry mattered as much as power.

The Man Behind the Monument: Afzal Khan Shirazi

Afzal Khan Shirazi was no ordinary minister. He was a Persian scholar who rose to become the grand vizier under one of India’s most celebrated emperors, Shah Jahan. His influence stretched across the empire, managing affairs of state while also nurturing a deep love for literature and the arts. Unlike many politicians of his time, Afzal Khan was equally comfortable composing verses in Persian as he was negotiating treaties or overseeing administrative reforms.

His tomb reflects this duality. It is both a political statement and a piece of art, a place where the intellectual and the material meet. The decision to use Chinese tiles was not just about beauty. It was a declaration of the Mughal court’s international reach and sophistication. During the seventeenth century, trade routes connected India with distant lands, and the Mughals were eager to showcase their cosmopolitan tastes. Afzal Khan’s resting place became a symbol of that openness, a fusion of cultures expressed in ceramic and stone.

The tomb’s design is more straightforward than other Mughal structures, but that simplicity carries its own elegance. There are no excessive carvings or towering minarets. Instead, the focus is on colour and geometry, on the way light plays across glazed surfaces. Over time, pollution from the river and the surrounding city has taken its toll. The vibrant hues have faded, and much of the tile work has been lost. Still, what remains is enough to hint at the monument’s former glory, enough to make you wonder what it must have looked like in its prime.

Why Chini ka Rauza Matters Today

In a country filled with grand palaces and towering forts, why should anyone care about a half-forgotten tomb? The answer lies in what Chini ka Rauza represents. It is a reminder that emperors and warriors do not just write history. It is also shaped by poets, scholars, and administrators like Afzal Khan, people whose contributions are less visible but no less critical. The monument also highlights the fragility of cultural heritage. While the Taj Mahal receives millions in funding for preservation, smaller sites like Chini ka Rauza struggle to survive.

Vandalism, pollution, and neglect have stripped away much of its original beauty. The tiles that once covered its walls are now scattered or gone entirely. This is not just an Indian problem. Around the world, lesser-known historical sites face similar threats. They lack the fame to attract tourists or the resources to fund proper maintenance. Yet they hold stories that are just as valuable, just as deserving of attention. Chini ka Rauza is also a testament to cultural exchange.

The use of Chinese tiles in a Mughal tomb shows how India has always been a crossroads of ideas and influences. Long before globalisation became a buzzword, the Mughals were incorporating foreign styles into their architecture, creating something entirely new in the process. That spirit of openness and experimentation feels especially relevant today. In times when borders and identities are often rigidly defined, monuments like this remind us of a past where cultures blended more freely.

Chini ka Rauza: A Visit Worth Making

If you find yourself in Agra, tired of the crowds at the Taj Mahal, Chini ka Rauza offers a different kind of experience. The site is usually quiet, sometimes nearly empty. You can walk around the tomb at your own pace, taking in the details without being rushed. The riverbank setting adds to the atmosphere. On certain days, when the light is right, the remaining tiles still catch the sun, giving a faint echo of the brilliance that once was.

Standing there, you can imagine Afzal Khan himself, a man who served an emperor but also loved poetry, who navigated the complexities of court politics while finding time to write. His tomb is a fitting tribute to that balance between duty and passion, power and art. It also serves as a quiet challenge. If monuments like this continue to decay, what stories will we lose? What lessons will future generations miss?

Preservation is not just about saving old buildings. It is about keeping alive the voices of people like Afzal Khan, whose lives and work continue to shape the world in ways that still matter. Chini ka Rauza may never have the fame of the Taj Mahal, but it has something equally valuable: authenticity. It is a place where history feels real, where you can still sense the human lives behind the stone and tile, where the past is not polished for tourists but simply present, waiting to be discovered.

Also Read: Tomb of Sher Shah Suri: An Emperor’s Dream Palace Floating On Water

You can connect with DNN24 on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel.