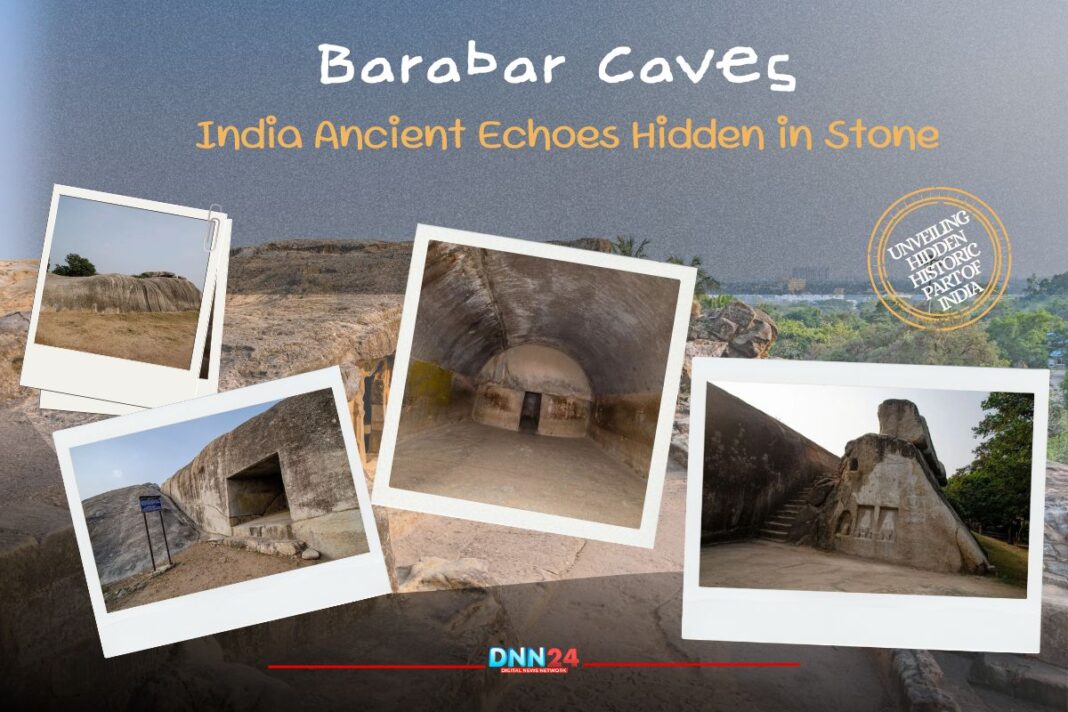

The Barabar Caves in Bihar hold secrets that most Indians have never heard about, even though they represent one of the finest examples of ancient Indian engineering. Located near Jehanabad in the quiet Barabar Hills, these rock-cut chambers were carved during Emperor Ashoka’s reign around 260 BCE for the Ajivika monks. This religious group has now disappeared from history. What makes these caves extraordinary is not just their age but the mirror-like polish on their granite walls, achieved without modern tools or technology. The Ajivikas believed in Niyati, the concept that destiny controls everything, and they needed isolated places for meditation during monsoon retreats.

Ashoka, despite being a Buddhist, donated these caves to the Ajivikas, proving that religious tolerance existed in India thousands of years ago. The four main caves, Lomas Rishi, Sudama, Vishwakarma, and Karan Chaupar, each tell different stories through their Brahmi inscriptions and architectural styles. Standing inside these chambers today, you can still hear your voice echo off the walls that witnessed the birth of rock-cut architecture in India. This tradition would later bloom into the magnificent caves of Ajanta and Ellora.

Barabar Caves : The Mauryan Engineering Mystery Nobody Can Fully Explain

The question that puzzles archaeologists and engineers alike is simple: how did ancient workers create surfaces smoother than most modern construction? The granite used in Barabar Caves ranks among the hardest rocks available, yet the interiors possess a finish so refined that visitors often mistake the walls for glass or metal. This level of precision required knowledge of stone properties, tool-making abilities, and patient craftsmanship that took years to complete.

Workers during the Mauryan period had access only to iron tools and possibly some abrasive materials, making the achievement even more remarkable. The caves were not painted or plastered but left in their natural, polished state, allowing the granite’s inherent beauty to speak for itself. Each cave served as a retreat hall for Ajivika ascetics who spent the monsoon months in meditation, protected from the heavy rains in Bihar.

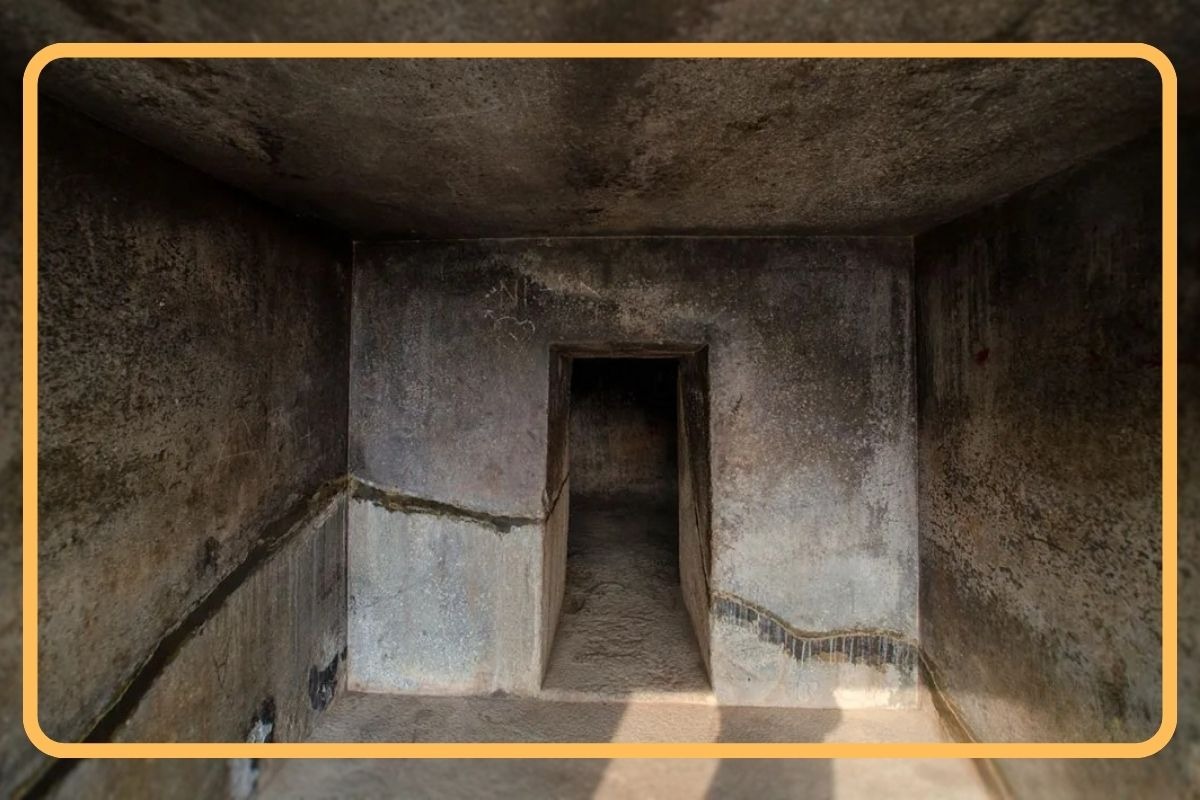

The rectangular and circular chambers were designed with acoustic properties that amplified chants and prayers, creating an atmosphere conducive to spiritual practice. Ashoka’s inscriptions, still visible after more than two millennia, were carved using Brahmi script and mention the caves as gifts to the Ajivika community. These inscriptions provide valuable information about religious practices, royal patronage, and the social structure of Mauryan India. The dedication required to hollow out solid granite mountains speaks volumes about the importance placed on religious freedom and spiritual pursuits during that era.

Lomas Rishi: Where Stone Pretends to Be Wood

The entrance to Lomas Rishi Cave stops visitors in their tracks because it looks exactly like a wooden doorway, complete with carved beams and decorative elements, except everything is solid rock. This architectural trick, called a chaitya arch, became a signature feature in Buddhist cave temples built centuries later across India. The facade depicts elephants advancing toward a stupa, symbolising the journey of souls toward enlightenment, and features detailed foliage patterns that showcase the artistic sensibilities of Mauryan artisans.

Walking through this entrance feels like stepping through a portal between the ordinary world and a sacred space where time moves differently. Inside, the cave remains relatively plain compared to its ornate entrance, following the Ajivika preference for simplicity in meditation spaces. The unfinished portions of Lomas Rishi suggest that work may have stopped abruptly, possibly due to political changes after Ashoka’s death or the gradual decline of Ajivika influence.

Historians believe this cave represents a transitional phase in Indian rock architecture, bridging earlier simple chambers with later elaborate Buddhist monuments. The craftsmanship visible in every carved elephant and leaf pattern proves that ancient Indian sculptors possessed skills equal to those of any civilisation of their time. The cave’s name, Lomas Rishi, likely refers to a sage from ancient texts, though the exact connection remains unclear.

Sudama and Karan Chaupar: The Emperor’s Personal Gifts

Sudama Cave carries a special historical weight because Ashoka’s inscription specifically mentions dedicating it to the Ajivikas during the twelfth year of his reign. This makes it not just a religious monument but a dated historical document carved in stone, allowing archaeologists to establish timelines for other Mauryan structures. The cave’s larger size compared to Karan Chaupar suggests it served as a gathering space for multiple monks during communal prayers or discussions.

Its polished walls create an almost supernatural effect when lit by lamps, as ancient practitioners would have experienced during evening meditation sessions. The rectangular layout follows practical considerations, providing maximum usable space while maintaining structural integrity within the granite hill. Karan Chaupar, though smaller, holds equal historical significance with its own Ashokan inscriptions mentioning monsoon retreats.

The tradition of rainy-season retreats arose from the practical need to avoid travel during floods and storms, but it evolved into an essential spiritual practice of intensive meditation. Both caves demonstrate how royal patronage supported religious minorities, with a Buddhist emperor funding Ajivika sanctuaries without imposing his own beliefs. The inscriptions use respectful language, addressing the monks with honour and expressing genuine devotion to their cause. These caves remind us that pluralism and mutual respect between different faiths have deep roots in Indian civilisation.

Vishwakarma Cave: When Architecture Becomes Prayer

Named after the divine craftsman of Hindu mythology, Vishwakarma Cave represents the peak of Barabar’s architectural achievement with its vaulted ceiling and spacious prayer hall. The ceiling curves upward in a way that mimics wooden barrel vaults, showing how stone carvers translated timber construction techniques into permanent rock form. At the chamber’s far end sits a small stupa, the focal point for circumambulation rituals where devotees would walk clockwise around the sacred structure while chanting or meditating.

This apsidal layout, with one curved end and one flat end, became standard in Buddhist architecture but appears here in an Ajivika context, suggesting shared architectural ideas across religious communities. The cave’s acoustics create a resonant effect, making even whispered prayers audible throughout the chamber, enhancing the meditative atmosphere. Unlike simpler caves that served individual hermits, Vishwakarma functioned as a community space where monks gathered for collective worship and teaching.

The craftsmanship evident in every detail, from the curved walls to the central stupa, reveals how seriously ancient Indians took their sacred architecture. Standing inside Vishwakarma Cave today, visitors can sense the spiritual energy that accumulated over centuries of devoted practice, even though the Ajivika religion itself has vanished from living memory.

Why These Forgotten Caves Matter Today

The Barabar Caves teach lessons that remain relevant in modern India, particularly about religious tolerance, architectural innovation, and cultural preservation. In an age when religious differences often spark conflict, these caves stand as proof that India’s greatest rulers once celebrated diversity by supporting faiths different from their own. The technical achievements visible in the polished granite inspire contemporary architects and engineers to study ancient methods that produced results still unmatched by many modern techniques.

As tourist destinations, the caves remain relatively unknown compared to later Buddhist sites, offering visitors a peaceful experience free of crowds and commercial distractions. Preserving these monuments requires ongoing effort from archaeological departments and local communities who understand their historical value.

The Barabar Caves represent the foundation of a rock-cut tradition that flourished across India for over a thousand years, making them essential for understanding the development of Indian art and architecture. They also serve as reminders of the Ajivika religion, now extinct, whose philosophical contributions to Indian thought deserve recognition alongside Buddhism and Jainism. Every visitor who makes the journey to these quiet hills helps keep alive the memory of Emperor Ashoka’s vision and the anonymous artisans whose skill created these timeless monuments.

Also Read: Tomb of Sher Shah Suri: An Emperor’s Dream Palace Floating On Water

You can connect with DNN24 on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel.