There exists a kind of writer who does not shout from stages or chase awards, but quietly stitches words into the fabric of a language until those words outlive the person who wrote them. Faheem Gorakhpuri was such a writer. Born Mirza Abdul Majeed sometime around 1878 in Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh, he lived through decades of colonial rule, famine, and social upheaval.

har dam batae jate hain hum bewafa nahin

Faheem Gorakhpuri

tum ko nahin yaqin to shak ki dawa nahin

Yet his response was not rebellion in the streets but rebellion on paper: sharp, truthful couplets that spoke for the invisible, the overlooked, the crushed. He died in 1942, months before the country gained independence, leaving behind no grand autobiography, no public monuments. What survived were a few dozen shers, compact as seeds, capable of sprouting meaning in any soil, in any century.

Faheem Gorakhpuri:A boy, a lamp, and the weight of words

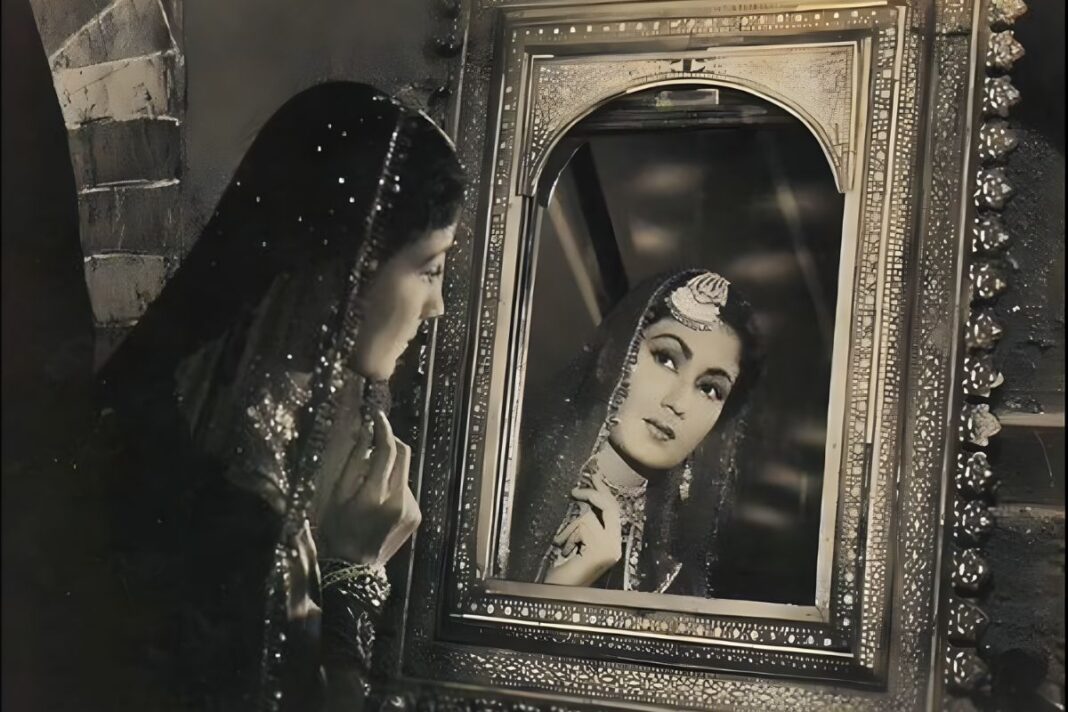

Gorakhpur in the late nineteenth century was not a place of comfort. It was a town where most people lived close to the edge, where a lamp was a luxury and education a distant dream for many. Faheem grew up in this setting, absorbing the rhythms of local speech, the textures of everyday struggle. His pen name, meaning “the wise one” or “the understanding one,” was perhaps a quiet hope rather than a boast. Unlike the grand ustads of Delhi or Lucknow, Faheem had no royal patrons, no wealthy sponsors. His poetry emerged from the soil of ordinary life: the shopkeeper’s worry, the labourer’s exhaustion, the mother’s unrecognised effort.

tum ko jo mujh se shikayat hai ki shikwa na karo

Faheem Gorakhpuri

banda-parwar hamein har roz sataya na karo

Records about his personal life are scarce. We know he belonged to a Mirza family, which suggests some cultural capital, perhaps some access to books and gatherings. But beyond that, the details blur. Did he teach? Did he work in some small government office? Did he marry, have children, argue with neighbours? The silence around his biography is almost deliberate, as if he chose to let his words speak for him alone.

The poetry of inner fire and outer dust

When you read Faheem Gorakhpuri, you do not encounter flowery metaphors or elaborate philosophical arguments. His ghazals are lean, direct, and almost stern. One of his most quoted couplets translates roughly to this: if you want a name, show the courage of a brave man and be ready to lay down your life. This is not romantic bravado. This is the voice of someone who has seen what it costs to stand upright in a world that prefers you bent. The word “naam” here does not mean fame in the modern sense. It implies integrity, character, a mark left by how you lived, not how many people knew your face.

ye sach hai un mein ye baaten to han hain

Faheem Gorakhpuri

baDe bad-zan nihayat bad-guman hain

In another well-known verse, he writes that the house is bright because of us, that we are the lamp of the home. On the surface, this is a simple statement. But when you place it in the context of his time, it becomes a declaration of self-worth from those who keep systems running yet remain nameless. The housewife, the clerk, the farmer, the worker: they are the real light. Faheem understood this deeply because he lived among them, perhaps as one of them.

aap ko ghair se ulfat ho gai

Faheem Gorakhpuri

han jabhi to mujh se nafrat ho gai

His couplets do not waste words. Every syllable is earned. This economy of language was not just a stylistic choice. It was survival. In an age when larger figures dominated Urdu poetry, Faheem carved out space by refusing to compete on volume. He competed in weight. A single sher of his could carry the emotional and moral heft of an entire nazm.

Gorakhpur as identity, not just address

Most Urdu poets adopt a takhallus, a pen name, often abstract or symbolic. Faheem chose to tie his identity to his birthplace. By calling himself Faheem Gorakhpuri, he was saying: I am not separable from this town, this dust, this accent, this struggle. In a literary culture that often looked toward Delhi, Lucknow, or Hyderabad as centres of refinement, Gorakhpur was peripheral. But Faheem wore that periphery as armour. He refused to erase his roots to sound more metropolitan.

ashk aankhon mein jigar mein dard sozish dil mein hai

Faheem Gorakhpuri

ek mohabbat ki badaulat ghar ka ghar mushkil mein hai

This choice resonates today. India is full of small towns producing talent that migrates to metros, often shedding their origins in the process. Faheem did the opposite. He planted his flag in the margins and wrote from there. His poetry reminds us that great work does not require a capital city. It requires honesty, discipline, and attention to the lives around you.

Why a 1942 voice matters in 2026

We live in an age of instant visibility. A person can become famous overnight and forgotten just as fast. In this environment, Faheem’s idea of “naam” feels radical. He suggests that a real name is not built on noise but on courage, on standing for something when it is difficult. His poetry asks: What are you willing to sacrifice for what you believe? Not for applause, not for followers, but for the dignity of having lived according to your own light.

iqrar hi ke sath ye inkar abhi se

Faheem Gorakhpuri

dil toDte ho kyon mera paiman-shikani se

His work also speaks to the unseen. In offices, homes, classrooms, and factories, there are millions whose labour keeps the world turning but whose names never appear anywhere. Faheem’s verse gives them language. You are the lamp. Without you, the house is dark. This is not flattery. This is recognition, and recognition is a form of justice.

han jhuT hai wo jaan se tum par fida nahin

Faheem Gorakhpuri

sach kah rahe ho ghair ka ye hausla nahin

For young writers, especially those working in Urdu or Hindi, Faheem offers a model of restraint and depth. In a culture that often rewards length and decoration, he shows that power can live in brevity. A single truthful line can outlast volumes of empty eloquence.

The flame that refuses to die

Faheem Gorakhpuri left no diaries, no letters, no recorded speeches. His life dissolved into time. But his shers remain, passed from mouth to mouth, copied into notebooks, shared on screens, recited in mushairas. They survive because they are true. They survive because they speak to something permanent in the human condition: the need for courage, the desire for respect, the knowledge that most of us will never be famous but can still choose to live with honour.

kyon kahun main ki sitam ka main saza-war na tha

Faheem Gorakhpuri

dil diya tha tujhe kis tarah gunahgar na tha

In remembering Faheem, we are not rescuing a relic. We are rekindling a way of thinking about poetry, about work, about what it means to leave a mark. His legacy is not in monuments or institutions. It is in the quiet persistence of his words, small flames in the dark, still burning.

Also Read:Ehsan Darbhangavi: Poet Who Carried His Teacher’s Soul

You can connect with DNN24 on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel.